ERS Charts of Note

Subscribe to get highlights from our current and past research, Monday through Friday, or see our privacy policy.

Get the latest charts via email, or on our mobile app for  and

and

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

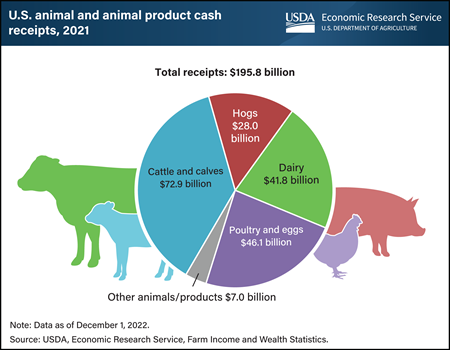

U.S. farm cash receipts from animals and animal products totaled $195.8 billion in 2021, led by receipts for cattle and calves at $72.9 billion (37 percent). Poultry and egg products made up the next largest share of 2021 cash receipts at $46.1 billion (24 percent), followed by dairy at $41.8 billion (21 percent), hogs at $28.0 billion (14 percent), and other animals and animal products at $7.0 billion (4 percent). As part of its Farm Income and Wealth Statistics data product, each year in late August or early September, USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) releases estimates of the prior year’s farm sector cash receipts from agricultural commodity sales. These data include cash receipt estimates by type of commodity, which can help in understanding the U.S. farm sector. The estimates may be revised as new information becomes available. Additional information and analysis are on the ERS Farm Sector Income and Finances topic page, updated December 1, 2022.

Thursday, January 12, 2023

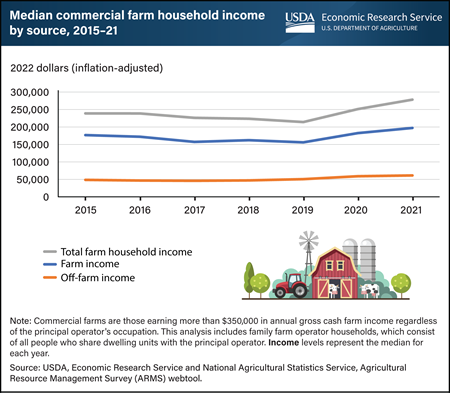

From 2015 to 2021, the median total household income for commercial U.S. farms rose an estimated 16 percent, to $278,339 from $238,994. Commercial farms earn more than $350,000 gross cash farm income regardless of the principal operator’s occupation. In 2021, the median total household income for commercial farms remained above the median income of $75,201 for all U.S. households. Farm households rely on a combination of on-farm and off-farm sources of income. On-farm income is determined by farm costs and returns that vary from year to year, and in any given year a majority of farm households report negative farm income. Off-farm sources—including wages, nonfarm business earnings, dividends, and transfers—are the main contributor to household income for most farm households. Because households operating commercial farms rely mostly on on-farm sources of income, they experience the largest shocks in household income when farm sector income rises or falls. This chart uses data from the new USDA, Economic Research Service and USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service’s Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) webtool, released in December 2022, as shown through the ARMS Farm Financial and Crop Production Practices data product.

Thursday, December 1, 2022

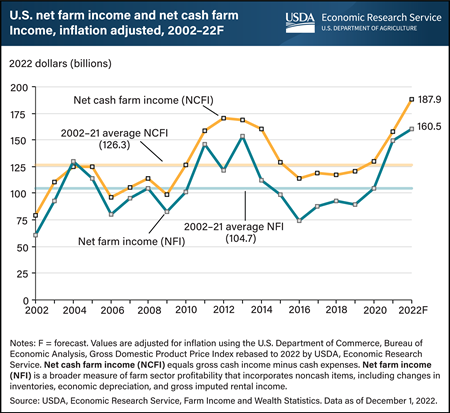

USDA’s Economic Research Service forecasts inflation-adjusted U.S. net cash farm income (NCFI)—gross cash income minus cash expenses—to increase by $30.1 billion (19.1 percent) to $187.9 billion in 2022. This total would be the highest on record for the inflation-adjusted data series. U.S. net farm income (NFI) is forecast to increase by $10.7 billion (7.2 percent) to $160.5 billion in 2022, its highest level since 1973 after adjusting for inflation. Net farm income is a broader measure of farm sector profitability that incorporates noncash items such as changes in inventories, economic depreciation, and gross imputed rental income. Cash receipts from farm commodities drive these income increases, with a projected increase of $78.5 billion (17.0 percent) to $541.5 billion, their highest level on record. In addition, total commodity insurance indemnities paid to farmers are expected to rise by $8.3 billion (70.1 percent) to $20.2 billion, also a record. Production expenses are forecast to increase by $46.6 billion (11.8 percent) to $442.0 billion in 2022, offsetting some income growth. Additionally, direct Government payments to farmers are projected to decrease by $11.0 billion (40.0 percent) from 2021 to $16.5 billion in 2022, mainly because of lower anticipated USDA and non-USDA payments for Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic assistance. Find additional information and analysis on the ERS topic page for Farm Sector Income and Finances, reflecting data released on December 1, 2022.

Wednesday, October 19, 2022

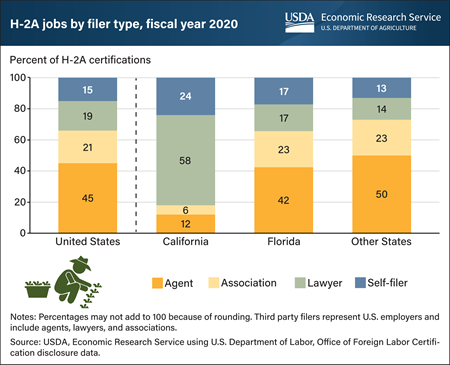

U.S. farmers who would like to hire temporary foreign workers through the H-2A visa program usually work with a third party (such as an agent, association, or lawyer) to make the application; employers themselves filed applications for only 15 percent of all jobs requested. Across the U.S., agents filed applications for 45 percent of all H-2A jobs, an association of farm enterprises filed for 21 percent of jobs, and 19 percent came from a lawyer representing the farmer. However, the usage rates for third parties differ across States. For instance, lawyers tend to file for most of the jobs in California, while agents and associations account for almost two-thirds of the job filings in Florida. The H-2A program allows farm operators who foresee a shortage of domestic workers to bring nonimmigrant foreign workers to the U.S. temporarily to perform agricultural labor or services. Many employers rely on specialized third parties to file H-2A applications on their behalf because of the perceived complexity of the process to certify their need for labor. Once a job is certified, the employer may then search for workers to employ. This chart appears in the ERS Economic Information Bulletin, The H-2A Temporary Agricultural Worker Program in 2020, published in August 2022.

Thursday, October 13, 2022

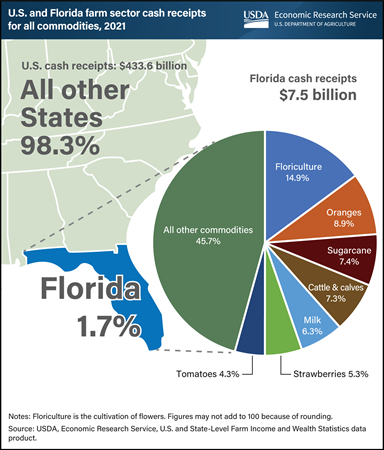

USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) annually estimates the previous year’s farm sector cash receipts—the cash income received from agricultural commodity sales. This data includes State-level estimates, which offer background information about States subject to unexpected events that affect the agricultural sector, such as Hurricane Ian, which swept across Florida and surrounding States in late September 2022. In 2021, commodities produced in Florida contributed about $7.5 billion (1.7 percent) of the $434 billion in total U.S. cash receipts. Floriculture, the cultivation of flowers, accounted for the largest share of Florida’s cash receipts. Valued at $1.1 billion (14.9 percent of the State’s total), floriculture receipts for Florida were higher than for any other State in 2021. The next largest commodities in Florida in terms of cash receipts were oranges ($670 million), sugarcane ($553 million), cattle and calves ($546 million), milk ($470 million), strawberries ($399 million) and tomatoes ($324 million). Certain Florida crops accounted for large percentages of U.S. cash receipts in 2021, such as sugarcane with 51 percent and oranges with 42 percent, while bell peppers and grapefruit accounted for roughly a third of U.S. production. In addition to floriculture, Florida led the nation in cash receipts for sugarcane, cabbage, cucumbers, watermelon, sweet corn, and snap beans. This chart uses data from the ERS U.S. and State-Level Farm Income and Wealth Statistics data product, updated in September 2022.

Monday, October 3, 2022

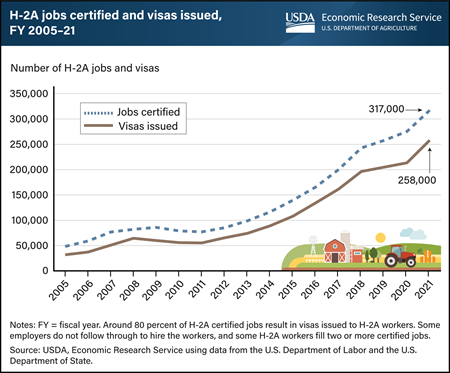

U.S. agricultural employers who anticipate a shortage of U.S. domestic workers can fill seasonal farm jobs with temporary foreign workers through the H-2A visa program. The Department of Labor certified around 317,000 temporary jobs in fiscal year (FY) 2021 under the H-2A visa program, more than six times the number certified in 2005. Only about 80 percent of the certified jobs in 2021 resulted in the issuance of a visa. The program has grown partly in response to current U.S. domestic workers finding jobs outside of U.S. agriculture and a drop in newly arrived immigrants who seek U.S. farm jobs. The H-2A program continued to expand in FY 2020 despite the jump in U.S. unemployment caused by lockdowns associated with the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Six States accounted for about half of the H-2A jobs filled in 2021 certified: Florida, Georgia, Washington, California, North Carolina, and Louisiana. Nationally, the average H-2A contract in FY 2020 offered 24 weeks of employment and 39.3 hours per week at an average hourly wage of $13. This chart updates information in the ERS bulletin The H-2A Temporary Agricultural Worker Program in 2020, published in August 2022.

Wednesday, September 14, 2022

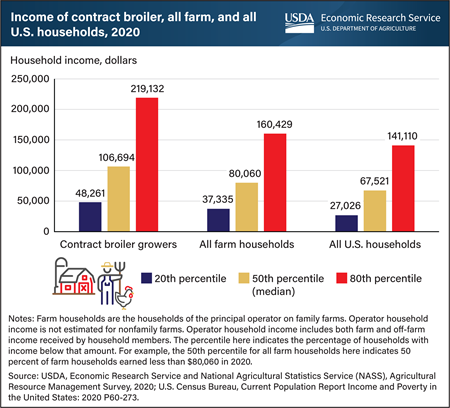

Farm households that raise broilers under contract have higher median incomes than U.S. farms and households overall. In 2020, the median income among all U.S. households was $67,251, while the median income among farm households was $80,060. The median for contract broiler growers was higher, at $106,694. These figures include on- and off-farm income. However, median income does not tell the whole story. The range of household incomes earned by contract broiler growers is wider than other groups. The bottom 20 percent of contract broiler growers earns $170,871 less than those in the top 20 percent, compared to $123,094 for all farm households, and $114,084 for all U.S. households. The wider range reflects, in part, the financial risks associated with contract broiler production. Grower compensation per bird can vary widely based on the productivity of the farm and the type of compensation system found in most broiler grower contracts. Sometimes called tournament-based systems, fees paid to the grower are based on the grower’s performance compared to other growers who provide birds to processing plants at the same time. This chart updates information found in the August 2014 Amber Waves feature “Financial Risks and Incomes in Contract Broiler Production.”

Thursday, September 1, 2022

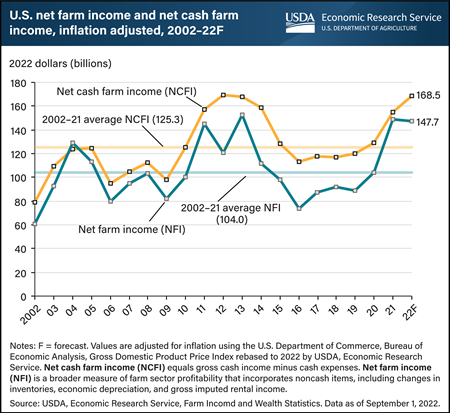

USDA’s Economic Research Service forecasts inflation-adjusted U.S. net cash farm income (NCFI)—gross cash income minus cash expenses—to increase by $13.5 billion (8.7 percent) from 2021 to $168.5 billion in 2022. This is the highest level since 2012. In comparison, U.S. net farm income (NFI) is forecast to fall by $0.9 billion (0.6 percent) from 2021 to $147.7 billion in 2022. This comes after NFI increased by $44.4 billion (42.6 percent) in 2021 to the highest mark since 2013. NFI is a broader measure of farm sector profitability that incorporates noncash items, including changes in inventories, economic depreciation, and gross imputed rental income. Both cash receipts and expenses are forecast to increase. Cash receipts for farm commodities are projected to rise by $66.3 billion (14.4 percent) from the previous year to $525.3 billion in 2022, their highest level on record. At the same time, production expenses are expected to increase by $44.4 billion (11.3 percent) to $437.3 billion in 2022, offsetting some of this income growth. Additionally, direct Government payments to farmers are projected to fall by $14.3 billion (52.5 percent) from 2021 to $13.0 billion in 2022, primarily because of lower anticipated USDA and non-USDA payments for Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic assistance. Find additional information and analysis on the USDA, Economic Research Service’s topic page for Farm Sector Income and Finances, reflecting data released on September 1, 2022.

Monday, August 29, 2022

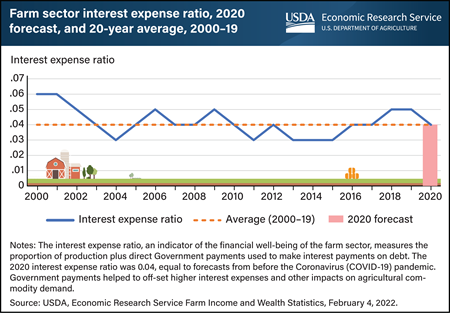

The interest expense ratio is one indicator of the financial well-being of the farm sector. For 2020, the ratio was 0.04, remaining in line with the long-term trend and initial forecasts despite the impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on reduced demand for agricultural commodities. The interest expense ratio is calculated by dividing interest expenses by the sum of the value of production and Government payments for a given year. Interest expenses are the costs incurred by farm operations when debt is used to finance farm activities. A lower interest expense ratio is preferable as it indicates that farmers are spending a smaller share of total revenue on interest expenses. A USDA forecast in February 2020 predicted interest expenses for 2020 at $18.0 billion, with a predicted interest expense ratio of 0.04. By February 2022, interest expenses for 2020 were estimated to be slightly higher than predicted at $19.4 billion. The February 2022 estimates also showed that while the value of production was lower than initially forecast, Government payments were higher. This resulted in an upward revision to the sum of the value of production and Government payments, offsetting the upward revision to interest expenses. That meant the interest expense ratio for 2020 remained consistent with the predicted value as well as the 20-year average of 0.04. The interest expense ratio was highest at 0.06 in 2000 and trended downward to a low of 0.03 multiple times from 2000 to 2020. This chart is drawn from data in the USDA, Economic Research Service COVID-19 Working Paper: Farm Sector Financial Ratios: Pre-COVID Forecasts and Pandemic Performance for 2020, published August 24, 2022.

_450px.png?v=7902.9)

Wednesday, August 10, 2022

A farmers market is a collection of two or more farm vendors selling agricultural products directly to customers at a common, recurrent physical location. According to USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS), from 1994 to 2019, the number of farmers markets rose from 1,755 to 8,771 in 2019, averaging growth of nearly 7 percent per year. Expansion began to slow in 2011 before eventually falling below a 1-percent per year increase between 2016 and 2017. Since then, growth in the number of farmers markets has remained modest and stable. A USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) report found that shares of local food sales have increased at intermediate market outlets, such as grocery stores, restaurants, and distributors. Increased availability of local products at these outlets corresponds with a plateau in purchases at direct-to-consumer outlets such as farmers markets and contributes to the observed slower growth relative to the prior two decades. According to market managers surveyed in the USDA’s AMS and NASS 2019 National Farmers Market Manager Survey, about two-thirds of farmers market vendors reported an increase in overall production and one-third reported increasing the number of workers they employed on their farm to meet demand. Additionally, an estimated 40 percent of vendors reported selling imperfect products that otherwise wouldn’t be sold in mainstream markets. Further, 77 percent noted that their participation led to the increased production of diverse products which in turn led to the expansion of offerings for farmers market clientele. This chart updates one found in the ERS report, Local Food Systems: Concepts, Impacts, and Issues, May 2010.

Tuesday, June 21, 2022

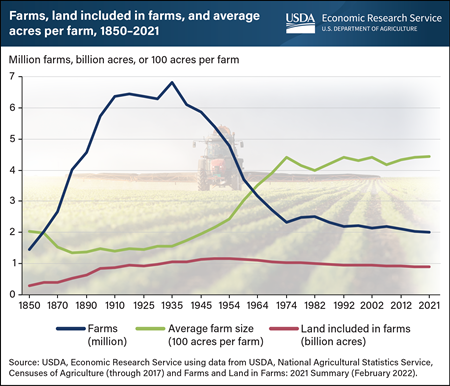

After peaking at 6.8 million farms in 1935, the number of U.S. farms and ranches fell sharply through the early 1970s. Rapidly falling farm numbers in the mid-20th century reflect the growing productivity of agriculture and increased nonfarm employment opportunities. Since then, the number of U.S. farms has continued to decline, but much more slowly. In 2021, there were 2.01 million U.S. farms, down from 2.20 million in 2007. With 895 million acres of farmland nationwide in 2021, the average farm size was 445 acres, only slightly greater than the 440 acres recorded in the early 1970s. This chart appears in the ERS data product Ag and Food Statistics: Charting the Essentials, updated June 2022.

Monday, April 18, 2022

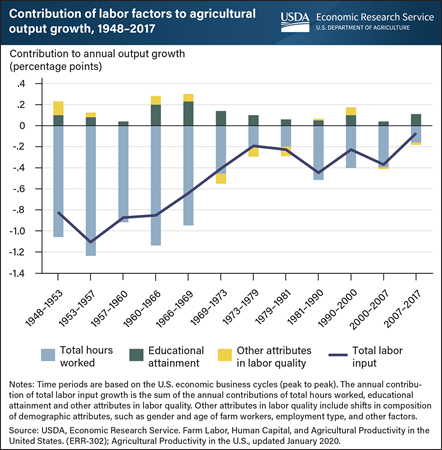

Agricultural output in the United States nearly tripled between 1948 and 2017, with average annual output growth at 1.53 percent. While reduction of labor hours worked has contributed negatively, changes in labor quality have contributed positively to output growth over the years. Labor quality includes shifts in composition of demographic attributes, such as gender, age, educational attainment, employment type and other factors. ERS researchers group the study period into 12 sub-periods in accordance with U.S. economic business cycles (from peak to peak). Most of the contraction in total hours worked occurred between 1948 and 1969, during the expansionary period after World War II. By the 2007–17 economic business cycle, the decline in labor hours had its lowest negative effect on output growth, -0.16 percentage points. ERS researchers found that total labor quality had a positive effect on output growth in all economic business cycles except the 1979-81 period. The effects of labor quality on agricultural output growth were especially prominent before 1969. It accounted for nearly 25 percent of total output growth per year in the 1948–53, 1953–57, and 1960–66 subperiods, and 14 percent of annual output growth in the 1966-69 subperiod. Except for the period immediately after WWII, the major source of labor quality changes was an increase in educational attainment among farmworkers. On average, the increase in educational attainment accounted for more than 90 percent of the changes in labor quality between 1948 and 2017. Nevertheless, since 1969, the rise in educational attainment has slowed, and the overall influence of labor quality on output growth has diminished. This chart is drawn from the USDA, Economic Research Service report “Farm Labor, Human Capital, and Agricultural Productivity in the United States,” published Feb. 15, 2022.

Wednesday, February 16, 2022

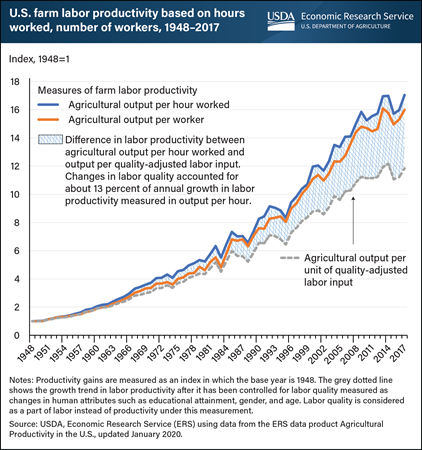

Agricultural output in the United States nearly tripled between 1948 and 2017 even as the amount of labor hours-worked declined by more than 80 percent. These opposing trends resulted in an increase in labor productivity growth in the U.S. farm sector. Labor productivity—calculated as average output per unit of labor input—is a popular measure for understanding economic growth. According to USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) estimates, agricultural output per worker grew by 16 times from 1948 through 2017. At the same time, agricultural output per hour worked grew even faster, by 17 times, implying that average hours worked per worker declined. Labor productivity estimates can vary based on different ways labor is measured. One factor in the increased labor productivity is the quality of labor, measured by attributes such as age, gender, and the highest level of education a worker has reached. Because these attributes may affect worker performance, ERS researchers accounted for labor quality changes in analyzing farm labor productivity. When labor quality changes since 1948 were accounted for, labor productivity grew at a slower rate than those based simply on hours worked or employment. The reason is because labor quality is treated as a part of labor input instead of productivity. This implies that changes in labor quality, such as improvements in education, account for much of the change in labor productivity over the last seven decades. ERS researchers estimate that changes to farm worker attributes accounted for about 13 percent of growth in hourly based annual labor productivity during the time studied. This chart in included in the ERS report Farm Labor, Human Capital, and Agricultural Productivity in the United States, published Feb. 15, 2022.

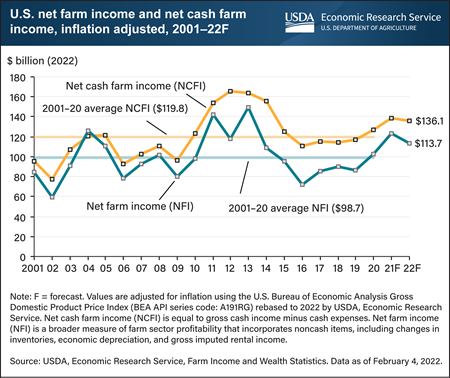

Friday, February 4, 2022

USDA’s Economic Research Service forecasts inflation-adjusted U.S. net cash farm income (NCFI)—gross cash income minus cash expenses—to increase by $12.6 billion (9.9 percent) to $139.0 billion in 2021 and then decrease by $2.9 billion (2.1 percent) to $136.1 billion in 2022. U.S. net farm income (NFI) is forecast to increase by $20.7 billion (20.1 percent) to $123.4 billion in 2021 and then decrease by $9.7 billion (7.9 percent) to $113.7 billion in 2022. Net farm income is a broader measure of farm sector profitability that incorporates noncash items, including changes in inventories, economic depreciation, and gross imputed rental income. If these forecasts are realized, both NCFI and NFI would remain above their respective 2001–20 averages in 2022. Underlying these forecasts, cash receipts for farm commodities are projected to rise by $13.7 billion (3.1 percent) to $461.9 billion in 2022, their highest level since 2014. During the same period, production expenses are expected to increase by $5.9 billion (1.5 percent) to $411.6 billion in 2022, offsetting some of this income growth. Additionally, direct Government payments to farmers are projected to fall by $16.4 billion (58.5 percent) from 2021 levels to $11.7 billion in 2022, largely due to lower anticipated USDA and non-USDA payments for Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic assistance. Find additional information and analysis on the USDA, Economic Research Service’s topic page for Farm Sector Income and Finances, reflecting data released on February 4, 2022.

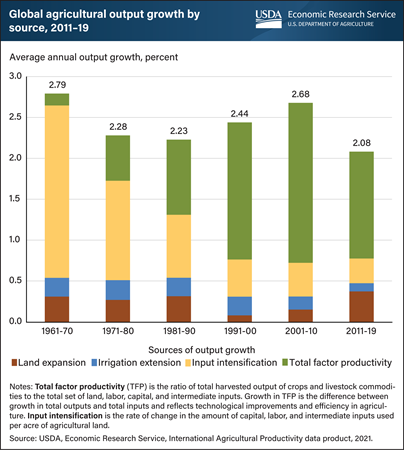

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

Since the 1960s, global agricultural output by volume has increased at an average annual rate of 2.3 percent, fluctuating between 2 and 3 percent on a decade-to-decade basis. In the latest decade (2011–19), the global output of total crop, animal, and aquaculture commodities grew an average rate of 2.08 percent per year. Several factors contribute to output growth, including expansion of agricultural land, extension of irrigation to existing cropland, the intensification of input use (more labor, capital, and material inputs per acre), and total factor productivity (TFP), a measure of the contribution of technological and efficiency improvements in the farm sector. Before the 1990s, most output growth came from increases in input use, including expansion of land, irrigation, and intensification of other inputs. Since the 1990s, growth in TFP, rather than growth in inputs, accounted for most of the growth in world agriculture output. From 2011 to 2019, TFP globally grew at an annual rate of 1.31 percent, accounting for nearly two-thirds of output growth. This chart comes from the USDA, Economic Research Service data product International Agricultural Productivity, updated in October 2021.

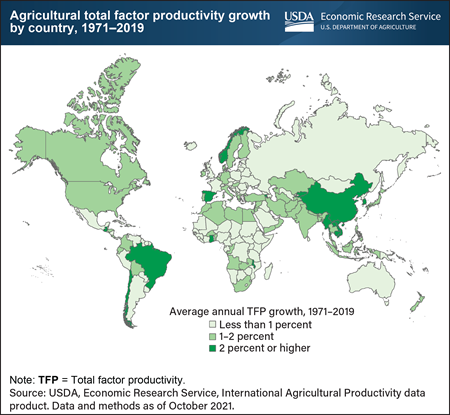

Friday, December 10, 2021

Total factor productivity (TFP) growth reflects the rate of technological and efficiency improvements in the agricultural sector and productivity growth varies across countries. TFP measures the amount of agricultural output produced from the combined set of land, labor, capital, and material resources employed in the production process. Agricultural TFP grew most rapidly (at more than 2 percent on average) in the dark green-colored countries and most slowly (or not at all) in the light green-colored countries. National policies and institutions, especially those that promote innovation and technical change, play a significant role in driving TFP growth in agriculture. Strengthening the capacity of national agricultural research and extension systems to develop and deliver new agricultural technologies to farmers has been a critical factor in raising agricultural productivity. Information from the International Agricultural Productivity data product and related ERS research show that that Brazil and India’s TFP growth can be attributed to long-term investments in agricultural research. China’s TFP growth can be attributed to investments in research and institutional and economic reforms. In contrast, Russia’s low rate of agricultural TFP growth is attributed to inefficiencies under a planned economy (until 1991) followed by economic disruptions that accompanied its transition to a market economy. Under-investment in agricultural research and extension and poor market infrastructure remain important barriers to stimulating agricultural productivity growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. This data can be found in the International Agricultural Productivity data product, last updated in October 2021.

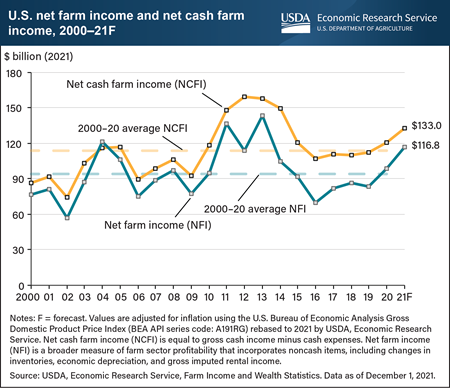

Wednesday, December 1, 2021

USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) forecasts inflation-adjusted net cash farm income (NCFI)—gross cash income minus cash expenses—to increase by $12.6 billion (10.5 percent) from 2020 to $133.0 billion in 2021. U.S. net farm income (NFI) is forecast to increase by $18.4 billion (18.7 percent) from 2020 to $116.8 billion in 2021. Net farm income is a broader measure of farm sector profitability that incorporates noncash items, including changes in inventories, economic depreciation, and gross imputed rental income. If this forecast is realized, NFI would be 24.2 percent above its 2000–20 average of $94.0 billion and the highest since 2013. NCFI would be 16.9 percent above its 2000–20 average of $113.8 billion and the highest since 2014. Driving these increases are cash receipts from farm commodities, which are projected to rise by $51.0 billion (13.5 percent) from 2020 to 2021, their highest level since 2014. Production expenses are expected to grow by $16.3 billion (4.4 percent) during the same period, somewhat moderating income growth. Additionally, direct Government payments to farmers are projected to fall by $20.2 billion (42.6 percent) in 2021. This decline follows record payments in 2020 and is largely due to lower anticipated payments from supplemental and ad hoc disaster assistance for Coronavirus (COVID-19) relief. Find additional information and analysis on ERS’s topic page for Farm Sector Income and Finances, reflecting data released December 1, 2021.

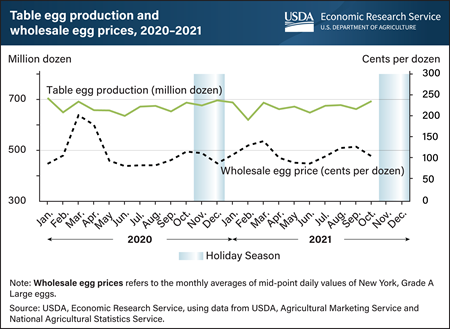

Tuesday, November 30, 2021

Demand for table eggs tends to increase when holiday gatherings and cold weather encourage home baking and cooking. In accordance, wholesale table egg prices—the prices retailers pay to producers for eggs—tend to increase ahead of holidays such as Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter. Leading up to the 2021 holiday season, however, wholesale prices of table eggs in the United States have fallen as effects of Coronavirus (COVID-19)-linked flock adjustments linger. In normal years, producers anticipate seasonal demand by adjusting the size of the table-egg laying flocks and the rate at which they produce eggs. In 2020, COVID-19-related disruptions in the demand for eggs led producers to reduce flock sizes. Flock sizes have slowly rebuilt since the summer of 2020 but remain smaller than the same time in 2019. However, the younger flocks produce more eggs per hen. The higher productivity can offset the effects of the small flock size and support increased production. At the beginning of October 2021 the size of the U.S. laying flock was just above the October 2020 levels and the rate of lay was 1.1 percent higher. This productivity bump is predicted to support about a 1 percent increase in October 2021 table egg production compared with a year ago, leading to a 9.6 percent price reduction compared to October 2020. This chart is drawn from the USDA, Economic Research Service Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry Monthly Outlook, published November 2021.

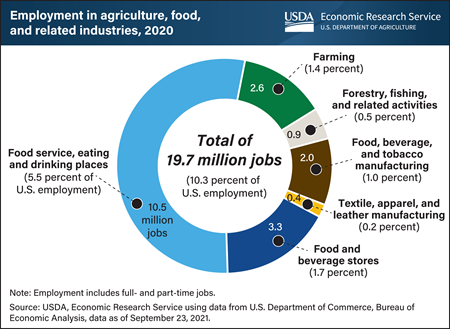

Friday, November 26, 2021

In 2020, 19.7 million full- and part-time jobs were related to the agricultural and food sectors,10.3 percent of total U.S. employment. Direct on-farm employment accounted for about 2.6 million of these jobs, or 1.4 percent of U.S. employment. Employment in agriculture- and food-related industries supported another 17.1 million jobs. Of this, food service, eating and drinking places accounted for the largest share at 10.5 million jobs. Food and beverage stores supported 3.3 million jobs. The remaining agriculture-related industries together added another 3.3 million jobs. This chart appears in the collection Ag and Food Statistics: Charting the Essentials on the ERS website.

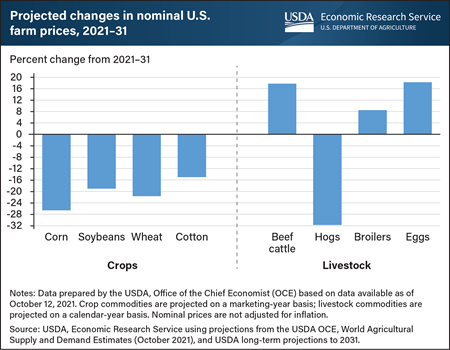

Wednesday, November 17, 2021

Recently released USDA projections reveal expectations for U.S. crop prices to decrease over the next 10 years while prices for major animal products, except hogs, are forecast to increase. Expected declines for crops follow a period of generally higher prices that have peaked during the current marketing year. The price-bolstering effects of economic recovery, renewed export demand, and logistical problems in supply chains are forecast to subside after the recent peak during the 2021/22 marketing year, and crop prices are forecast subsequently to return to the earlier pattern of generally lower prices through 2031. Hog prices are projected to follow a similar pattern to crops and to move toward levels that reflect normal weather and an absence of major market shocks including policy changes. Beef cattle and broiler prices are expected to demonstrate a modest increase in the early years of the projection period before leveling off to slower growth, resulting in an average price increase of 8 to 17 percent over the decade. Similar to most animal products prices, prices that farmers are expected to receive for their eggs are forecast to rise steadily throughout the projection period, partly based on increased demand for cage-free eggs and regulatory changes that are projected to increase costs of production. This chart is based upon forecasts and projections using data available as of October 12, 2021, and long-term projections to 2031 released on November 5, 2021. Current projections are shown in the Economic Research Service’s (ERS) Agricultural Baseline Database. For 2020’s farm price projections, see the ERS Chart of Note from November 9, 2020.