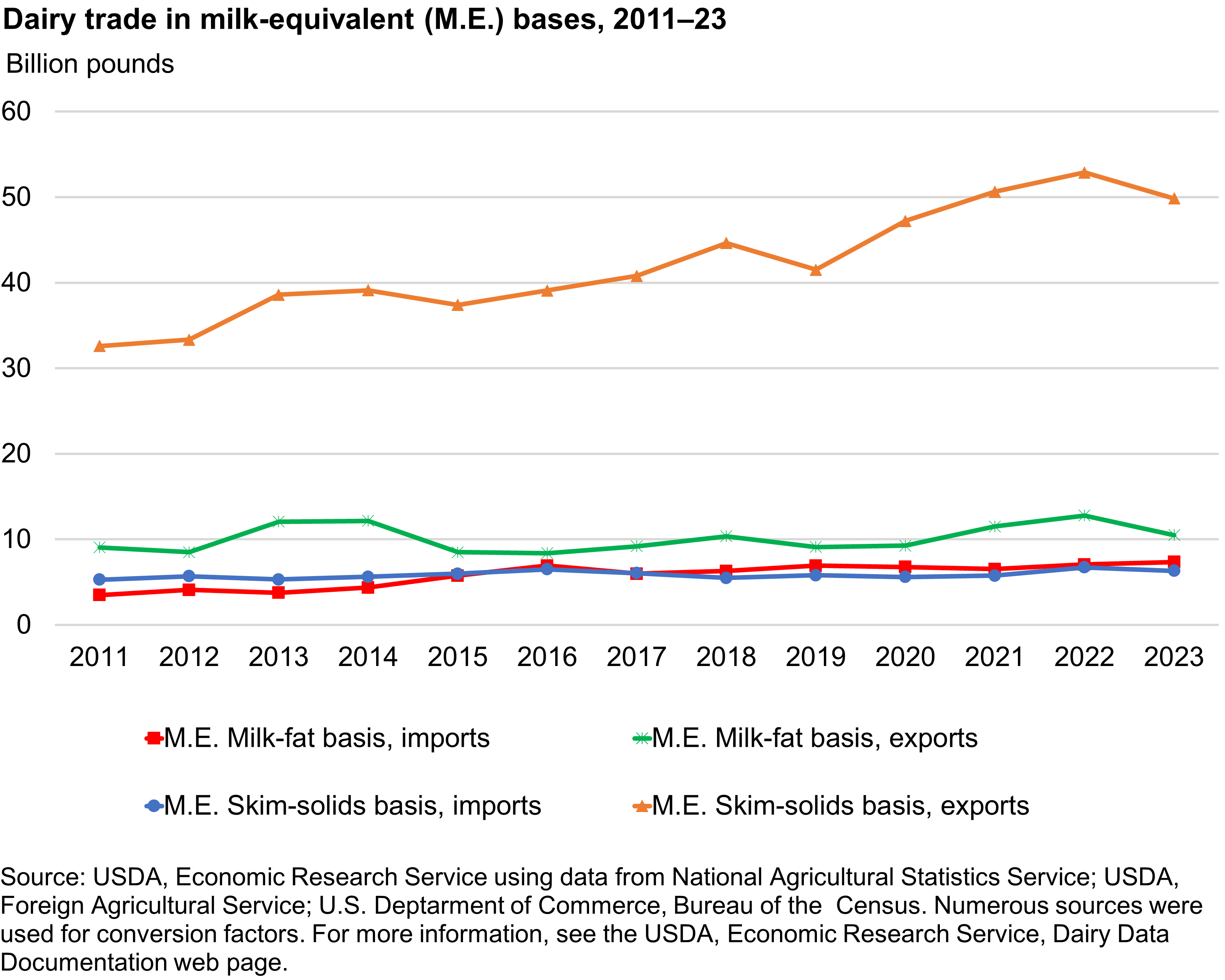

In 2023, dairy export volumes declined on both milk-fat and skim-solids milk-equivalent bases after reaching record-high values in 2022. However, prior to 2023, dairy export volumes had been trending upward, especially on a skim-solid milk-equivalent basis. Meanwhile, dairy imports have been relatively stable from 2011 to 2023.

Download chart data in Excel format.

The United States competes with other large dairy suppliers including New Zealand, the European Union (EU), Australia, and emerging dairy exporter countries such as Argentina and Uruguay.

There are several reasons why U.S. dairy product exports have grown over the years:

- Income growth in Mexico, Canada, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Central America, South America, and other regions of the world led to an increase in dairy product consumption facilitated by rising global trade.

- Free trade agreements (FTAs) with various countries have provided the United States with greater access to world markets. For example, dairy exports to Mexico increased through the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), previously known as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). USMCA replaced NAFTA on July 1, 2022. Under USMCA, tariffs on dairy products traded between the United States and Mexico remain at zero, as it was under NAFTA. However, tariffs on dairy trade between the United States and Canada are gradually introducing new access for dairy products to trade in both directions over several years.

- China’s market-based reforms, including those related to its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, opened what is now the world’s largest market for dairy product imports.

- Both the EU and the United States reduced domestic support and export subsidies for dairy products in recent years, bringing about greater competition in world markets.

A series of trade negotiations known as the Uruguay Round led to the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) on January 1, 1995. Before the WTO, the United States used explicit dairy product import quotas to shield the domestic dairy industry from international dairy markets. As a member of the WTO, the United States, along with many other dairy-trading countries, established tariff rate quotas (TRQs) for dairy products. TRQs allow imports at low tariffs up to fixed amounts. Any additional imports are subject to higher tariff rates. Many TRQs are administered through licenses for imports of specific products from specific countries or regions. Imports have been liberalized further through FTAs with some countries.

A point of contention between the United States and the EU has been the use of geographical indications (GIs). The WTO defines GIs as “indications which identify a good where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographical origin.” For several years, the EU has been pushing for the extension of protections for GIs to cover certain foodstuffs. At issue for the dairy industry are certain types of cheese names, such as Parmesan, feta, and provolone. The EU seeks an international registration and protection system, as well as the removal of generic terms for various products. The EU has entered into some FTAs that include provisions concerning GIs and have been steadfast in their inclusion during all new FTA negotiations. The United States and many other countries maintain that existing WTO rules concerning GIs are sufficient and that EU expansion of GI protections precludes competition for similar products from other nations.

On January 1, 2020, the U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement went into effect. In this agreement, Japan committed to provide substantial market access for the United States by phasing out most tariffs, enacting meaningful tariff reductions, or allowing a specific quantity of imports at a lower duty. Most tariff reductions for dairy products will take place over several years.

On January 15, 2020, the United States and China signed the U.S.-China Economic and Trade Agreement (Phase One). China agreed to increase imports of agricultural products and to make some changes to several non-tariff trade issues. On February 18, 2020, as part of this agreement, China announced a new round of tariff exclusions for U.S. agricultural commodities (including some dairy products) affected by the additional tariffs previously levied by China. China-based importers must apply for the tariff exclusions.

For more information, see

- USDA, Foreign Agricultural Service, Dairy Products

- USDA, Foreign Agricultural Service, Global Agricultural Trade System (GATS)

- USDA, Foreign Agricultural Service, Production Supply and Distribution Online (PS&D)

- USDA, Economic Research Service, Foreign Agricultural Trade of the United States (FATUS)

- Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR)