Cattle production is the most important agricultural industry in the United States, consistently accounting for the largest share of total cash receipts for agricultural commodities. In 2023, cattle production is forecast to represent about 17 percent of the $520 billion in total cash receipts for agricultural commodities. With rich agricultural land resources, the United States has developed a beef industry that is largely separate from its dairy sector. The U.S. beef industry is unique when compared with countries like India that produce beef from water buffalo, which are used as dual-purpose animals. In addition to having the world's largest fed-cattle industry, the United States is also the world's largest consumer of beef—primarily high-value, grain-fed beef. The U.S. beef cattle industry is often divided into two production sectors: cow-calf producers and cattle feeding.

U.S. Cattle Production

Cattle Cycle

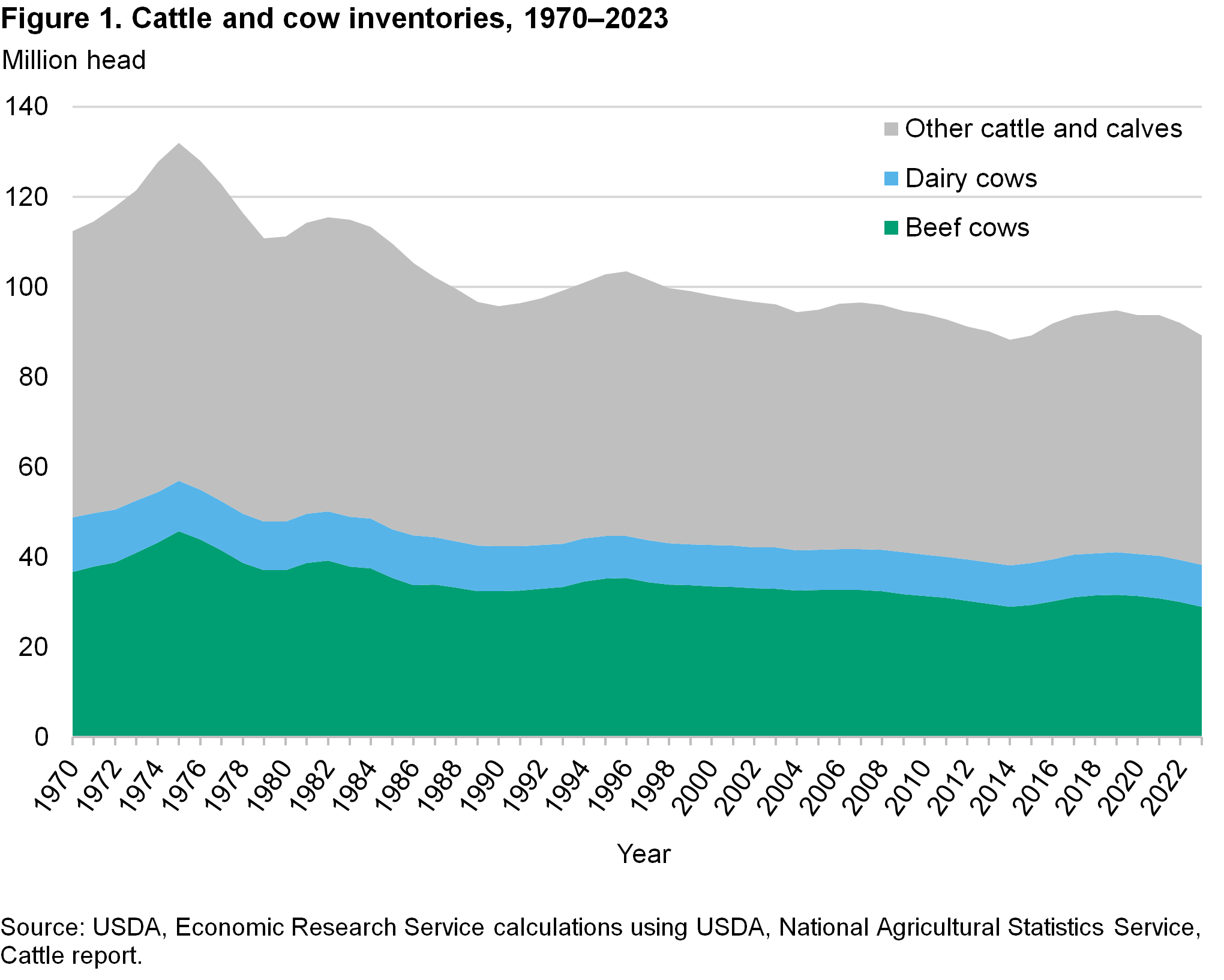

The cattle cycle is a period of time that describes cattle producers’ decisions to grow and decrease the size of their herds that collectively affect the size of the national cattle herd—the total number of all cattle and calves. The cattle cycle averages 8–12 years, from low point to low point, and it is influenced by the combined effects of cattle prices and input costs that drive cow-calf producer profitability; the gestation period for cattle; the time needed for raising calves to market weight; and climate conditions. Specifically, if cattle prices and producer revenues are expected to rise, producers may expand their herds; if prices are expected to decline substantially, producers reduce their herds by culling older cows and keeping fewer heifers to replace older cows or to add to their herd. Also, cow-calf producers’ response to profit fluctuations may appear delayed because of the lengthy gestation period for cattle relative to hogs and poultry. The total number of beef cattle in the United States is highly dependent on the stage in the cattle cycle.

Adverse climate, like persistent dry conditions leading to drought, can diminish pastures conditions and reduce harvested feed supplies, which can alter a cycle’s direction and duration. For example, the last full cattle cycle began in 2004 with 94.4 million head of cattle and calves, including both beef and dairy cattle. The herd expanded for 3 years to 96.6 million head until increasing feed and energy prices caused producers to reduce their herds. Then, drought conditions decreased pasture and forage availability, forcing producers to further cull cows and limit heifer retention at a more rapid pace, accelerating contraction from 2011 through 2014.

By late 2013 and early 2014, grazing conditions improved and feed prices decreased. However, as each year’s calf crop shrank as the number of beef cows declined, progressively fewer feeder calves were placed in feedlots and, subsequently, fed to a particular weight and marketed for slaughter. These combined effects increased feeder calf prices, which helped to improve cow-calf profitability. A 7-year liquidation of the national cattle herd ended January 1, 2014, at 88.2 million cattle and calves, which was the smallest herd size since 1952. Since then, the cattle herd has grown to a peak of 94.8 million head in 2019. As of January 1, 2023, the herd has decreased by 6 percent to 89.3 million cattle head. The USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) provides information on cattle inventory in its semi-annual Cattle reports.

Download chart data in Excel format.

Cow-Calf Operations

Cow-calf operations mainly maintain a herd of beef cows for raising calves. Most calves are born in the spring and weaned at 3 to 7 months. Following the weaning stage, calves can move through the value chain in several different ways. Some of the female calves (heifers) and male calves (bulls) may be retained in the herd or sold to another producer. If additional pasture forage is available at weaning, then some calves may be retained for further grazing and growth until the following spring when they would be sold. Throughout the United States, cow-calf operations are located on land not typically suited or needed for crop production. These operations depend on range and pasture forage conditions, which in turn depend on the area’s variations of average rainfall and temperature. Beef cows graze on forage from grasslands to maintain themselves and raise a calf with very little, if any, grain input. The cow is maintained on pasture year-round, as is the calf until it is weaned. Based on the USDA, NASS 2017 Census of Agriculture, the average beef cow herd is about 44 head. Operations with 50 or fewer head are often part of multi-enterprises, or they provide supplemental income to off-farm employment. Operations with 100 or more beef cows compose 9.9 percent of all beef operations and 56.0 percent of the beef cow inventory.

Cattle Feeding

When calves are weaned, producers must decide if they should retain some heifer and bull calves to replace older cows and bulls or to expand their herds. The remaining bulls are castrated to become steers, and together with the remaining heifers not kept in the herd, are sold into the feeding system for slaughter. There are different ways for these new steers and heifers for slaughter to grow to market weight. After being weaned, the calves may enter a stocker program, where they will graze on grass for 3 to 4 months before being placed in a feedlot. Another option is to move calves into a 30- to 60-day preconditioning program. Within this program, the calves go through an animal health protocol for deworming, dehorning, and vaccinating so calves can then be started on feed to ensure they are healthy in the next stage of the value chain. Another option is for the calves to be backgrounded for 90–120 days, placed in pens or lots and fed dry forage, silage, and grain before entering a feedlot.

A feedlot is the final stage of cattle production. It provides a confined area for feeding steers and heifers on a ration of grain, silage, hay, and/or protein supplement to produce a carcass that will meet the USDA quality grade Select or better for the slaughter market. The USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) grades beef as whole carcasses in two ways: (1) quality grades for tenderness, juiciness, and flavor; and (2) yield grades for denoting the amount of usable lean meat on the carcass. The quality grades are Prime, Choice, and Select. Depending on weight at feedlot placement, feeding conditions, and desired grade, the feeding period can be 90 to 300 days. Average gain is from 2.5–4 pounds per day on about 6 pounds of dry-matter feed per 1 pound of gain. Although most of a calf's nutrients come from grass until it is weaned, feedlot rations are generally 70–90 percent grain and protein concentrates.

Cattle feeding operations are concentrated in the Great Plains region but are also located in parts of the Corn Belt, Southwest, and Pacific Northwest regions. Feedlots with less than 1,000-head capacity comprise most of U.S. feedlot operations, but they market a relatively small share of the fed cattle. Conversely, although feedlots with 1,000-head-or-greater capacity are less than 5 percent of total feedlots, they market 80–85 percent of fed cattle. Feedlots with a capacity of 32,000 head or more market around 40 percent of fed cattle. The industry continues to shift toward a small number of very large, specialized feedlots focused on raising high-quality cattle for a particular market, such as markets requiring cattle not treated with hormones and not fed beta agonists. USDA, NASS provides monthly Cattle on Feed reports.

Policy

Federal Government assistance provided to the cattle sector is limited to emergency measures approved for a specific scope and time period. Federal assistance addresses the needs of producers suffering losses due to drought, hot weather, disease, insect infestation, flood, fire, hurricane, earthquake, severe storms, extreme cold, or other natural disasters. See the Disaster Assistance Programs section of USDA's Farm Service Agency (FSA) website for information on current programs.

The sector trends toward fewer and large enterprises, which brings environmental issues to the forefront of public policy regarding the U.S. livestock industry. As animal density (i.e., number of animals per unit of land area) increases, so do concerns about air and water quality, the occupational health of livestock workers, and waste management. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reports the environmental requirements for the production of livestock in Animal Feeding Operations.

Any product used as an animal feed ingredient is regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine distributes uniform feed-ingredient definitions and feed-labeling standards to ensure safe use of animal foods.

Cattle are also affected by other government policies and programs related to animal health, food safety, and mandatory price reporting.

U.S. Beef and Cattle Trade

Trade

Most beef produced in and exported from the United States is grain-fed and marketed as high-value cuts. In 2022, the USDA, Foreign Agricultural Service’s Production, Supply and Distribution forecasts ranked the United States as the second largest beef exporter behind Brazil, although it often has been a net importer.

As U.S. beef production expands and contracts with the cattle production cycle, it will affect the amount of imported beef needed for processing to make ground beef products. When the cattle herd contracts in a downward trend, more domestic cows and bulls are slaughtered. Increasing domestic availability of lean beef and decreasing the need for import. The amount of beef exported is mainly affected by domestic beef production. Similarly, beef traded in the global marketplace responds to beef availability. Cattle production tends to follow a multiyear cycle that can cause the domestic beef supply to vary. See UDSA, ERS Sector at a Glance web page for information on the cattle cycle.

Download chart data in Excel format.

Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy Effects on U.S. Cattle and Beef Trade

In May 2003, the United States banned Canadian cattle imports following Canada's first case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). In July 2005, U.S. imports of Canadian cattle for immediate slaughter or for finishing in a U.S. feedlot resumed for cattle younger than 30 months old. In November 2007, USDA expanded imports to include live cattle of all ages from Canada and any other country recognized as presenting a minimal risk of introducing BSE into the United States. Currently, Canada is the only minimal-risk country designated by the United States. All animals born after Canada's 1997 feed ban are eligible to be imported into the United States. For the latest requirements for exporting U.S. live animals and animal products by country destination, visit USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) animal and animal product export information and, for the latest information about importing live animals into the United States, visit animal and animal product import information.

Simultaneously, in December 2003, the discovery of the first U.S. BSE case in a dairy cow imported from Canada led many U.S. trading partners to restrict some U.S. beef products or to completely ban all U.S. beef and cattle. Two more cases of BSE in the United States—in Texas (June 2005) and in Alabama (March 2006)—were subsequently reported. The reported BSE cases significantly altered U.S. beef export patterns in 2004. Japan, South Korea, China, and various other countries ceased importing U.S. beef and beef products for several years. Although Mexico and Canada initially closed their borders to U.S. beef imports, they reopened trade within a matter of months.

In 2011, U.S. beef exports reached 2.8 billion pounds in carcass-weight equivalents, which surpassed 2003’s historic record of 2.5 billion pounds. In 2013, the World Organization for Animal Health upgraded the United States’ BSE status to “negligible risk”—the highest status available—based on the United States’ history with the disease, the implementation and enforcement of the U.S. feed ban, and the USDA BSE surveillance system. For the latest details on the export eligibility and requirements for U.S. beef to specific countries, see USDA, Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) Import & Export Library.

Want more information?

- Economic Impacts of Feed-Related Regulatory Responses to Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy(Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry Outlook, September 2008).

- An Economic Chronology of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy in North America (Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry Outlook, June 2006).

- Did BSE Announcements Reduce Beef Purchases?(Report No. ERR-34, December 2006)

Information on BSE from other USDA agencies:

Beef Exports

U.S. beef exports in 2022 reached a new record at 3.5 billion pounds, an increase of more than 3 percent from the previous record set in 2021. The main reason for the rise was a 16 percent increase in exports to China, growing from over 540 million pounds in 2021 to about 627 million in 2022.

U.S. beef exports to China have benefited from the Economic and Trade Agreement between the United States and the People’s Republic of China—also known as the Phase One agreement—which expanded market access on March 17, 2020. The agreement eliminated several long-standing nontariff barriers established at the reopening of the market in 2017 following a 14-year absence due to BSE.

In 2019, the year before the Phase One agreement entered into force, U.S. beef accounted for about 1 percent of China imports on both a volume and value basis. In 2022, U.S. market share rose to almost 7 percent by volume and 10 percent by value. However, U.S. exports are likely below their full potential due to remaining market access barriers, such as the ban on the feed additive ractopamine.

In 2022, the top five U.S. beef export markets comprised 80 percent of total beef exports (by volume): Japan, South Korea, China, Mexico, and Canada. The United States’ two largest beef markets, Japan and South Korea, accounted for about 46 percent of U.S. exports. The third largest market was China, accounting for 18 percent of exports. Mexico and Canada, representing the North American beef trade, accounted for 16 percent of total exports.

Download chart data in Excel format.

Beef Imports

U.S. beef imports in 2022 totaled 3.4 billion pounds, over 1 percent above 2021 and the largest volume since 2005. Canada, the largest beef supplier, accounted for 29 percent of total U.S. beef imports in 2022. The United States’ second and third largest beef sources were Mexico and Brazil, providing about 22 and 14 percent of U.S. beef imports, respectively. Australia, the fourth major supplier, shipped 12 percent of U.S. beef imports. New Zealand, the fifth major source, supplied 12 percent of the U.S. beef import needs. U.S. Imports from Brazil have grown almost threefold since the year prior to USDA’s approval of fresh meat imports from Brazil.

Download chart data in Excel format.

Live Cattle Trade

Traditionally, the United States imports more cattle than it exports. Canada and Mexico are the only significant cattle suppliers to the U.S. market because of their geographical proximity and because of how their cattle and beef sectors complement the U.S. sector. From 2018 to 2022, Mexico provided about 63 percent of U.S. cattle imports, and nearly all of the imports were lighter-weight cattle intended for U.S. stocker or feeder operations. Of the cattle imports from Canada, about 79 percent were designated for immediate slaughter; on average, 59 percent of these cattle were fed steers and heifers and 41 percent were cows and bulls. About 28 percent of the cattle imported from Canada went to U.S. feedlot operations. Lastly, less than 2 percent of cattle imported from Canada were used for breeding.

U.S. cattle exports to Canada and Mexico vary from year to year across both the total numbers exported and the relative percentages exported to each country. Historically, the United States has primarily exported slaughter cattle to both Canada and Mexico in addition to some feeder cattle to Canada. However, new markets for U.S. cattle exports of dairy and beef females for breeding have emerged in recent years, including Vietnam, Qatar, Pakistan, Turkey, and Russia.

For the latest trade data, see Livestock and Meat International Trade Data. These reports contain monthly and annual data for imports and exports of live cattle, hogs, sheep, and goats. The tables only display quantities, and the beef and veal, pork, and lamb and mutton data are reported on a carcass-weight-equivalent basis. Breakdowns by country are included. For the current U.S. meat and animal trade outlook, see the USDA, ERS Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry Outlook report and the USDA, Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) semi-annual Livestock and Poultry: World Markets and Trade reports.

Download chart data in Excel format.