ERS Charts of Note

Subscribe to get highlights from our current and past research, Monday through Friday, or see our privacy policy.

Get the latest charts via email, or on our mobile app for  and

and

Friday, June 29, 2018

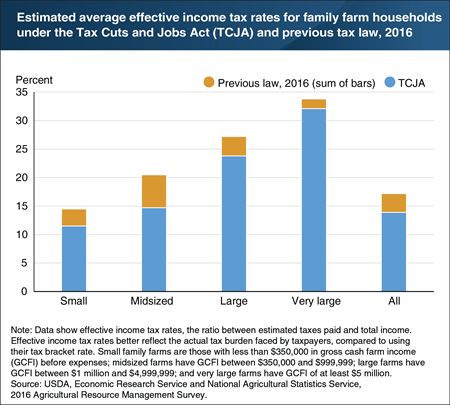

In 2016, family farm households faced an estimated income tax rate of 17.2 percent on average. However, the recently passed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 eliminates or modifies many itemized deductions and tax credits, while lowering tax rates on individual and business income. The TCJA also expands some business provisions. Had the TCJA been in place in 2016, ERS estimates that family farm households would have faced a lower average income tax rate of 13.9 percent. The effects of the TCJA varies by farm size, with the greatest reduction for households operating midsized farms. The average income tax rate for households of midsized farms would have decreased by 5.8 percentage points. By comparison, the average income tax rate for households operating large farms would have decreased by 3.4 percentage points, for small farms by 3.0 percentage points. The expansion of the standard deduction is a primary reason households operating smaller farms are estimated to face lower income tax rates, while those operating large farms benefit more from reductions in individual tax rates and a new provision allowing a portion of farm income to be excluded from household taxable income (income from farming is taxed at the individual level for family farms). Midsized farms are expected to benefit from all these provisions. This chart appears in the June 2018 ERS report, Estimated Effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on Farms and Farm Households.

Friday, June 15, 2018

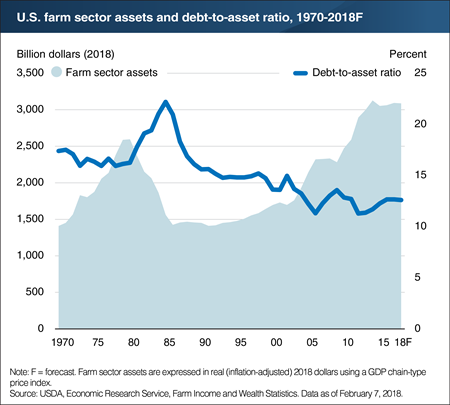

The debt-to-asset ratio compares the farm sector’s outstanding debt relative to the value of the sector’s aggregate assets. An indicator of the farm sector’s level of risk exposure, this ratio provides a measure of the sector’s ability to repay financial liabilities (debt) via the sale of assets. A lower debt-to-asset ratio indicates fewer assets are financed by debt and suggests the sector would be better able to overcome adverse financial events. After reaching a low of 11.3 percent in 2012, the debt-to-asset ratio increased gradually to 12.7 percent in 2016 as the growth rate for debt exceeded the growth rate for assets. ERS forecasts the debt-to-asset ratio to remain relatively unchanged in 2017-18, as farm sector assets stabilized at $3.1 billion (adjusted for inflation) between 2016 and 2018. Still, the ratio remains well below the peak in 1985 (22.2 percent) as farm sector asset values have nearly doubled since 1985. About 80 percent of the value of farm sector assets is attributable to the market value of farm real estate assets, which increased 115 percent from 1985 to 2016 and is forecast to increase 2 percent in 2017 and remain flat in 2018. This chart uses data from the ERS data product Farm Income and Wealth Statistics, updated February 2018.

Wednesday, May 23, 2018

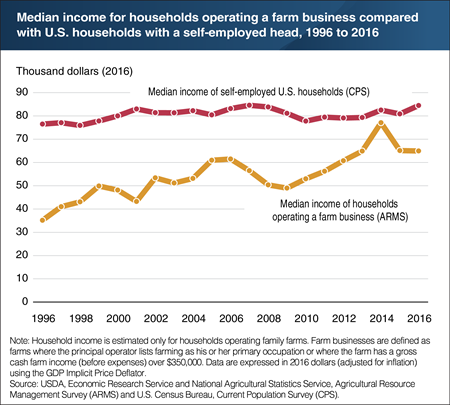

Households that operate farm businesses—which include farmers with commercial farms earning at least $350,000 in gross cash farm income before expenses and those with smaller farms who report farming as their primary occupation—account for two-fifths of U.S. farm households. Since 1996, the median income of these farm business households has remained below the income of self-employed households. However, the median income gap between farm business and self-employed households has varied and has narrowed considerably during this period. Over the past 20 years, after adjusting for inflation, the median income of farm business households has increased substantially. This has occurred both because farms have become more profitable and average off-farm income has risen. In 1996, the median income of farm business households was $35,166, compared to $76,483 for self-employed households. By 2016, the median income of farm business households had increased to $64,929, compared to $84,459 for self-employed households. This chart appears in the ERS topic page Farm Household Well-being, updated May 2018.

Wednesday, April 11, 2018

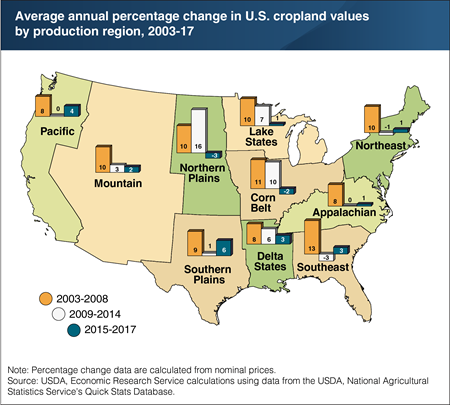

Farm real estate (including farmland and the structures on the land) accounts for over 80 percent of farm sector assets and represents a significant investment for many farms. Two major uses of farmland are cropland and pastureland. From 2003 to 2014, U.S. cropland values appreciated faster than pastureland—with cropland values doubling in real terms. However, cropland appreciation varied over time and by region. Between 2003 and 2008, cropland values appreciated almost uniformly across regions. Between 2009 and 2014, cropland appreciation was highest for the Northern Plains, Lake States, Corn Belt, and Delta States. This reflected the relatively steep rise in commodity prices for the grain and oilseed often grown in those regions, which made the cropland more valuable. However, between 2015 and 2017, the Northern Plains and Corn Belt experienced negative cropland appreciation, reflecting falling commodity prices and farm income. Regional differences in land values may also be due to varying demands for farmland for nonagricultural purposes, such as demand for oil and gas development in shale areas. The leveling or decline of cropland values observed in the Northeast, Southeast, and Pacific regions from 2009 to 2014 was likely a result of the Great Recession, which negatively influenced the value of cropland in close proximity to urban areas. This chart updates data found in the February 2018 ERS report, Farmland Values, Land Ownership, and Returns to Farmland, 2000-2016.

Thursday, March 22, 2018

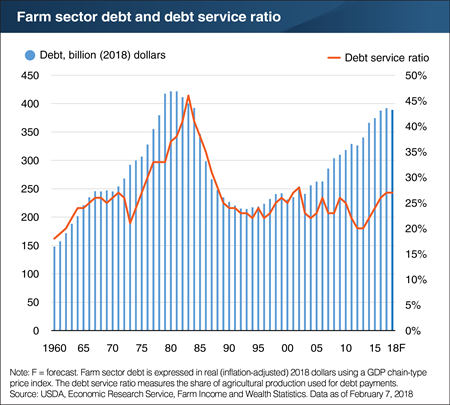

The farm sector debt service ratio measures the share of agricultural production used for debt payments. It provides a way to assess the farm sector’s ability to make scheduled interest and principal payments on farm debt when they are due. A higher debt service ratio implies a greater share of production income is needed to make debt payments, suggesting lower liquidity (the amount of capital readily available as cash). Following record-level agricultural production in 2013, the debt service ratio in 2012 and 2013 was at its lowest level since 1962 at 20 percent. The ratio then increased year-over-year to 26 percent in 2016. ERS forecasts the debt service ratio to increase slightly to 27 percent in 2017 and 2018, as debt payments have increased and the value of agricultural production has declined since 2013. However, the ratio remains well below the peak in 1983 even as farm sector debt approaches levels seen in the 1980s. Declining interest rates have helped to keep debt payments low, and the value of agricultural production has increased 38 percent since 2002, after adjusting for inflation. As a result, the debt service ratio is now near its 2002 value and its 35-year historical average. This chart uses data from the ERS data product, Farm Income and Wealth Statistics, updated February 2018.

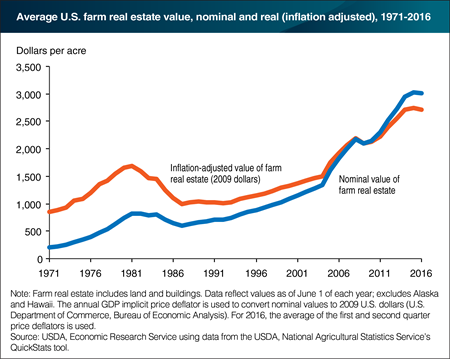

Friday, February 23, 2018

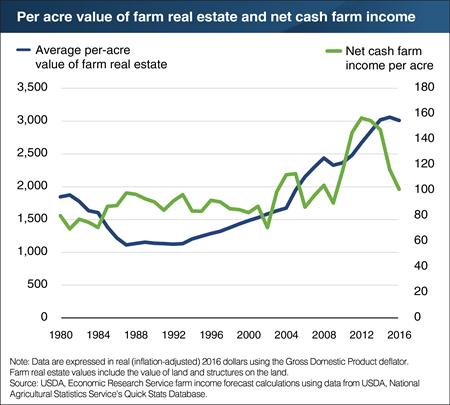

Farm real estate (including land and the structures on the land) accounts for over 80 percent of farm sector assets and represents a significant investment for many farms. U.S. farm real estate values have been rising since the farm crisis of the 1980s, reaching record high values in 2015. Beginning in the mid-2000s, higher farm incomes and lower interest rates contributed to rapid appreciation. Nationally, average per-acre farm real estate values more than doubled when adjusted for inflation, from $1,483 in 2000 to $3,060 in 2015. Cropland appreciated faster than pastureland (reflecting the relatively steep rise in grain and oilseed commodity prices), while farmland in the Midwest appreciated faster than other areas of the country. However, farmland appreciation slowed considerably from 2015 to 2016, with some regions experiencing small declines caused by falling commodity prices and net cash farm income. This chart appears in the February 2018 ERS report Farmland Values, Land Ownership, and Returns to Farmland, 2000-2016.

Wednesday, February 7, 2018

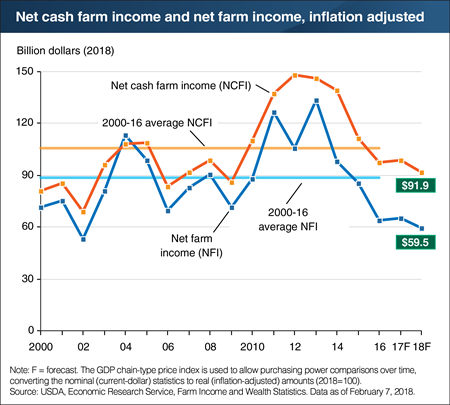

U.S. net farm income is forecast to decline $5.4 billion (8.3 percent) to $59.5 billion in 2018, while U.S. net cash farm income is forecast to decline $6.7 billion (6.8 percent) to $91.9 billion (adjusted for inflation). The forecast declines are the result of changes in cash receipts and production expenses. Additionally, Government payments are forecast to decline $2.3 billion (20.0 percent) in inflation-adjusted terms; this is due largely to a forecast slight recovery in prices for many crops covered by the Price Loss Coverage program, combined with lower Agriculture Risk Coverage program revenue guarantees due to lower recent commodity prices for the crops covered under that program. If realized, 2018 net farm income would be the lowest since 2002 and net cash farm income would be at its lowest level since 2009. Both profitability measures remain below their 2000-16 averages, which included substantial increases in crop and animal/animal product cash receipts from 2010 to 2013. Net cash farm income includes cash receipts from farming as well as farm-related income, including government payments, minus cash expenses. Net farm income is a more comprehensive measure of profits that incorporates noncash items, including changes in inventories, economic depreciation, and gross imputed rental income. Find additional information and analysis on ERS’s Farm Sector Income and Finances topic page, released February 7, 2018.

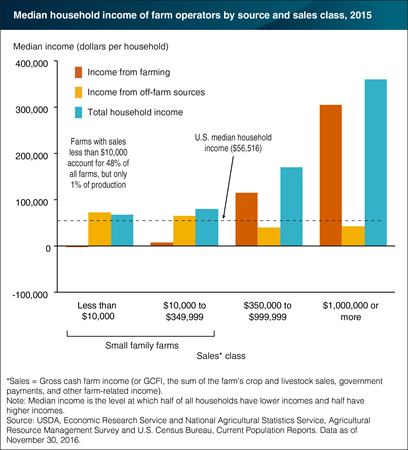

Friday, January 26, 2018

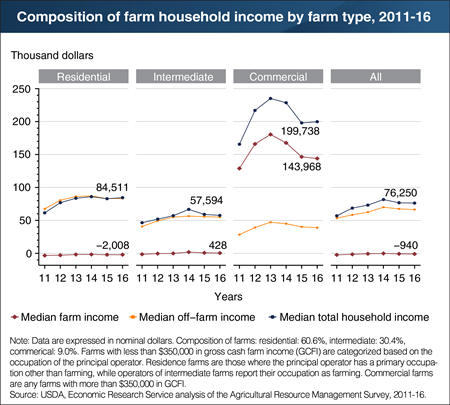

Most farm households rely on off-farm income, such as wages from a job outside the farm. Typically, only commercial farm households receive a substantial share of their income from the farm. For example, in 2016, the median farm income was negative $2,008 for households operating residence farms (where the operator primarily works off-farm or is retired from farming), while median off-farm income was $83,400. Households operating intermediate farms (smaller farms where the operator’s occupation is farming) also earn the bulk of their income from off-farm sources. In contrast, households operating commercial farms—where gross cash income is $350,000 or more—derive most of their income from the farm (nearly $144,000 in 2016). Changes to their total household income follow profits from farming. Most agricultural production takes place on commercial farms. In 2016, residential and intermediate farms together accounted for over 90 percent of U.S. family farms and one-quarter of the value of production. By comparison, commercial farms accounted for 9 percent of family farms and three-quarters of production. This chart is based on data from the ERS data product Farm Household Income and Characteristics, updated November 2017.

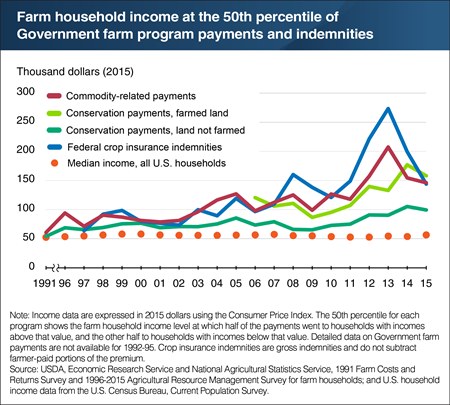

Friday, December 1, 2017

USDA’s commodity, Federal crop insurance, and conservation programs provided about $16.9 billion in financial assistance to farm producers and landowners in 2015. Over time, as agricultural production shifted to larger farms, these programs’ payments shifted to higher-income households—which often operate larger farms. In 1991, half of commodity program payments went to farms operated by households with incomes over $60,717 (adjusted for inflation). By 2015, this midpoint value, at which half of payments went to households with higher incomes, was $146,126. Similar trends hold for other programs, though with variability across programs and over time. For example, the midpoint income level for crop insurance indemnity payments increased from 2010 to 2013, but by 2015 had dropped below the 2008 level, to $143,806. For context, the median U.S. household income shows little change over the period and in 2015 was $56,516. Payments from commodity programs reduce financial risks to specific commodity producers, while payments from federally subsidized crop insurance mitigate yield and revenue risks. Payments from conservation programs aim to conserve natural resources and reduce environmental impacts from farming. This chart appears in the ERS report The Evolving Distribution of Payments from Commodity, Conservation, and Federal Crop Insurance Programs, released November 2017.

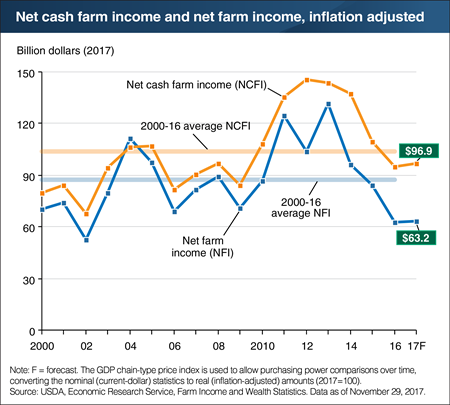

Wednesday, November 29, 2017

After several years of decline, net farm income in 2017 for the U.S. farm sector as a whole is forecast to be relatively unchanged at $63.2 billion in inflation-adjusted terms (up about $0.5 billion, or 0.8 percent), while inflation-adjusted U.S. net cash farm income is forecast to rise almost $2.0 billion (2.1 percent) to $96.9 billion. Both profitability measures remain below their 2000-16 averages, which included substantial increases in crop and animal/animal product cash receipts from 2010 to 2013. Net cash farm income and net farm income are two conventional measures of farm sector profitability. Net cash farm income measures cash receipts from farming as well as cash farm-related income, including government payments, minus cash expenses. Net farm income is a more comprehensive measure that incorporates noncash items, including changes in inventories, economic depreciation, and gross imputed rental income. Find additional information and analysis on ERS’s Farm Sector Income and Finances topic page, released November 29, 2017.

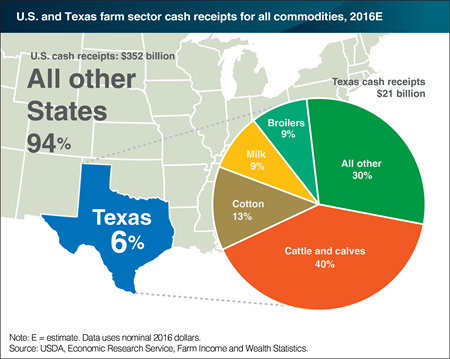

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

Each August, as part of its Farm Income data product, ERS produces estimates of the prior year’s cash receipts—the cash income the farm sector receives from agricultural commodity sales. This data product includes State-level estimates, which can help offer background information about States subject to unexpected changes that affect the agricultural sector, such as the recent hurricane that struck Texas. In 2016, U.S. cash receipts for all commodities totaled $352 billion. Texas contributed about 6 percent ($21 billion) of that total, behind only California and Iowa. Cattle and calves accounted for 40 percent ($8 billion) of cash receipts in Texas, compared to 13 percent nationwide. Only Nebraska had higher cash receipts for cattle and calves in 2016. Texas led the country in cash receipts from cotton at almost $3 billion (13 percent of the State’s receipts), accounting for 46 percent of the U.S. total for cotton. Milk and broilers each accounted for 9 percent of cash receipts in Texas. The State ranked sixth in both milk and broiler cash receipts nationwide. This chart uses data from the ERS U.S. and State-Level Farm Income and Wealth Statistics data product, updated August 2017.

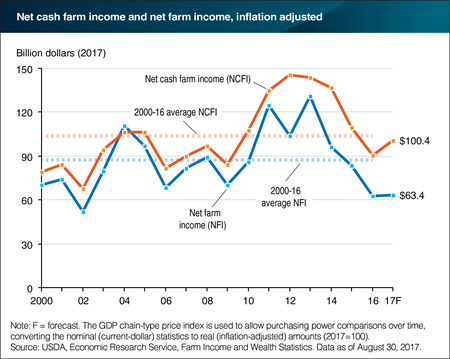

Wednesday, August 30, 2017

After several years of declines, inflation-adjusted U.S. net farm income is forecast to increase about $0.9 billion (1.5 percent) to $63.4 billion in 2017, while inflation-adjusted U.S. net cash farm income is forecast to rise almost $9.8 billion (10.8 percent) to $100.4 billion. The expected increases are led by rising production and prices in the animal and animal product sector compared to 2016, while crops are expected to be flat. The stronger forecast growth in net cash farm income, relative to net farm income, is largely due to an additional $9.7 billion in cash receipts from the sale of crop inventories. The net cash farm income measure counts those sales as part of current-year income, while the net farm income measure counts the value of those inventories as part of prior-year income (when the crops were produced). Despite the forecast increases over 2016 levels, both profitability measures remain below their 2000-16 averages, which included surging crop and animal/animal product cash receipts from 2010 to 2013. Net cash farm income and net farm income are two conventional measures of farm sector profitability. Net cash farm income measures cash receipts from farming as well as farm-related income including government payments, minus cash expenses. Net farm income is a more comprehensive measure that incorporates non-cash items, including changes in inventories, economic depreciation, and gross imputed rental income. Find additional information and analysis on ERS’s Farm Sector Income and Finances topic page, released August 30, 2017.

Friday, June 30, 2017

In recent years, farm real estate (including farmland and buildings) has accounted for about 80 percent of the value of U.S. farm assets—amounting to about $2.4 trillion in 2015. Strong farm earnings and historically low interest rates have supported the increase in farmland values since 2009. Since 2014, farm real estate values in many regions have leveled off; and, in 2016, the national average per-acre value declined slightly. This is partly a response to the recent declines in farm income, which may temper expectations of future farm earning potential. In addition, the 2016 USDA 10-year commodity outlooks suggest that the prices of major commodities will all stabilize at, or grow modestly from, their current price levels—which are significantly lower than those in 2011. Expectations of interest rate increases, which have been noted in some U.S. farm regions, also put downward pressure on land values. Given that farm real estate makes up such a significant portion of the balance sheet of U.S. farms, changes in its value can affect the financial well-being of individual farms and the farm sector. Over 60 percent of U.S. farmland was owner-operated in 2014; for these owners, increases in real estate values make it easier to obtain credit and service debt. For the farmers who rent the remaining 39 percent of farmland, higher real estate values can lead to higher rent expenses. This chart appears in the ERS topic page for Farmland Value, updated April 2017.

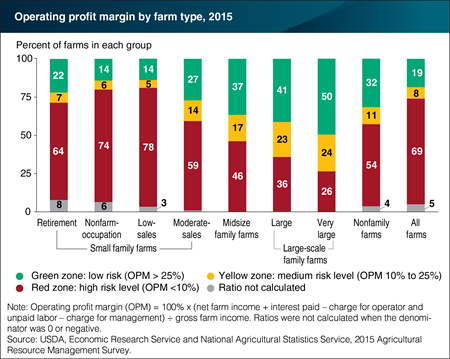

Tuesday, May 9, 2017

Ongoing innovations in agriculture have enabled a single farmer, or farm family, to manage more acres or more animals. Farmers who take advantage of these innovations to expand their operations can reduce costs and raise profits because they can spread their investments over more acres. In 2015, larger family farms displayed stronger financial performance, on average, than smaller farms. For example, 74 percent of very large family farms—those with gross farm cash income (GCFI) of $5 million or more—had estimated operating profit margins (OPM) of at least 10 percent. This represents the safer yellow and green zones, with lower financial risk. By comparison, 54 percent of midsize family farms (GCFI of $350,000 to $999,999) also had an OPM of at least 10 percent. Most small farms (GCFI under $350,000) in the red zone (OPM under 10 percent), had a negative OPM, the result of losses from farming. Small farms account for 90 percent of U.S. farms, but only contribute about a quarter of the value of production. The majority of their operator households’ income comes from off-farm sources. This chart appears in the March 2017 Amber Waves data feature, "Large Family Farms Continue To Dominate U.S. Agricultural Production."

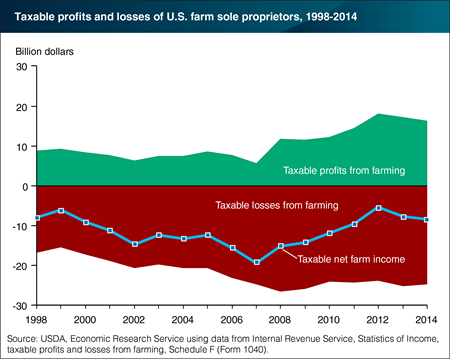

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

Nearly 90 percent of family farms are structured as sole proprietorships. These entities are not subject to pay income tax themselves; rather, the owners of the entities (farmers) are taxed individually on their share of income. Numerous Federal income tax law provisions allow farmers to reduce their tax liabilities by reporting losses. From 1998 to 2008, for example, taxable losses from farming (the red area of the chart) rose from $16.7 billion to $24.6 billion. This was due, in part, to changes in the tax code beginning in 2001 that expanded the ability of farms to deduct capital costs—such as tractors and machinery—in the year the equipment was purchased and used. Between 2007 and 2014, strong commodity prices bolstered farm-sector profits (the green area), but taxable net farm income (the blue line) remained negative. Farm sole proprietors, in aggregate, have reported negative net farm income since 1980; in other words, they’ve reported a farm loss due to higher farm expenses than income. In 2014, the latest year for which complete tax data are available, U.S. Internal Revenue Service data showed that nearly 67 percent of farm sole proprietors reported a farm loss. This chart appears in the ERS topic page for Federal Tax Policy Issues, updated January 2017.

Friday, March 24, 2017

In 2015, farm households had a median total income of $76,735 per household—a third greater than that of all U.S. households ($56,516). Median total household income increased with farm size, with the median income of households operating small family farms approximating the U.S. median household and those operating larger family farms far exceeding it. The source of household income also varied with farm size: As farm size decreased, off-farm income represented a larger share of total household income. Households operating midsize and large farms (gross cash farm income or GCFI greater than $350,000) earned the majority of their total household income from their farm operations. By comparison, more than half of households operating small farms (GCFI less than $350,000) incurred small losses from farming, so the majority of their total household income came from off-farm sources. Wages from off-farm jobs accounted for more than half of off-farm income across all farm households. Farm households also receive significant income from transfers (such as Social Security or private pensions), interest and dividends, and non-farm business income. This chart appears in the ERS data product Ag and Food Statistics: Charting the Essentials, updated March 2017.

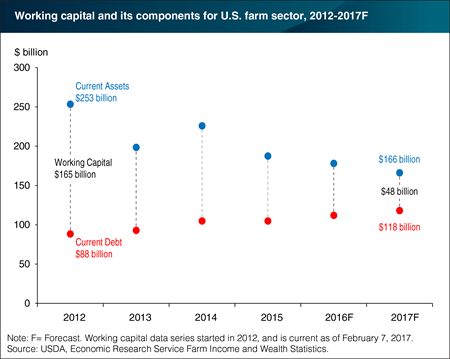

Monday, February 27, 2017

Farm financial liquidity describes how easily the U.S. farm sector can convert assets to cash in order to meet its short-term debt obligations. One measure of liquidity is working capital, the difference between current assets (such as cash and inventory) and short-term debt. Higher working capital means better financial health for the farm sector. ERS expects that working capital for the farm sector could contract to $48 billion by the end of 2017. The erosion in working capital was caused both by the reduction in the value of current assets (down $87 billion since 2012) and growing current debt (up $30 billion since 2012). Although working capital has weakened since ERS started tracking this measure in 2012, this decline followed record highs in net cash farm income from 2011 to 2013. The balance sheet forecast also indicates that farm solvency ratios—which measure whether debt can be met in a timely manner—are favorable compared to 25-year historical averages. However, farm solvency has weakened for 5 consecutive years; taken together with the decline in working capital, this pattern reflects a modest increase in farm financial risk exposure for the sector as a whole. This chart is based on the ERS Farm Income and Wealth Statistics data product, updated February 7, 2017.

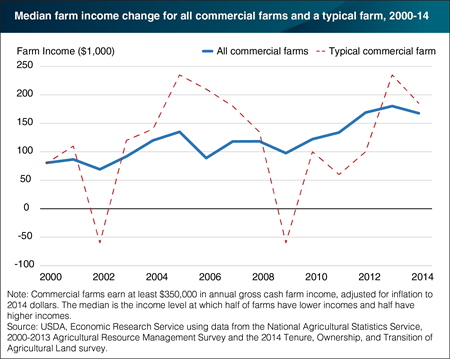

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

Commercial farm income is highly variable from year to year, fluctuating with output and prices. Income variability can affect key farm decisions, including how much to invest in farm assets (such as land or machinery) and how much to save as a cushion for low-earning years. Aggregate statistics, like the median income for all farms, can provide useful insight into how the farm sector as a whole fares from year to year—but can mask considerable variation for individual farms. For example, farms in one region might be thriving, whereas in another region they might be experiencing low incomes due to a localized drought. Between 2000 and 2014, median farm income for commercial farms ranged from about $70,000 to $180,000, with income fluctuating between consecutive years an average of $20,000. By comparison, a typical (representative) commercial farm with the same average income as the median commercial farm (about $120,000) could see its income fluctuate much more—with an average income swing of $86,000. This chart appears in the ERS report “Farm Household Income Volatility: An Analysis Using Panel Data From a National Survey,” released February 2017.

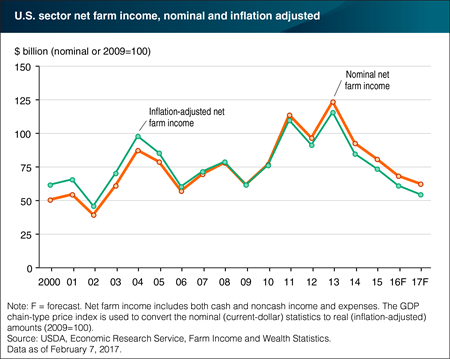

Tuesday, February 7, 2017

Net farm income is a conventional measure of farm sector profitability that is used as part of the U.S. Gross Domestic Product calculation. Following several years of record highs, net farm income trended downward from 2013 to 2016. For 2017, ERS forecasts net farm income will fall to $62.3 billion ($54.8 billion in inflation-adjusted terms). If realized, this would be an 8.7 percent decline from the prior year and a decline of 49.6 percent from the record high in 2013. The expected decline in 2017 net farm income is driven by a forecast reduction in the value of production. Crop value of production is forecast down $9.2 billion (4.9 percent), while the value of production of animal/animal products is forecast to decline by less than $1 billion (0.5 percent). Find additional information and analysis in ERS’ Farm Sector Income and Finances topic page, released February 7, 2017.

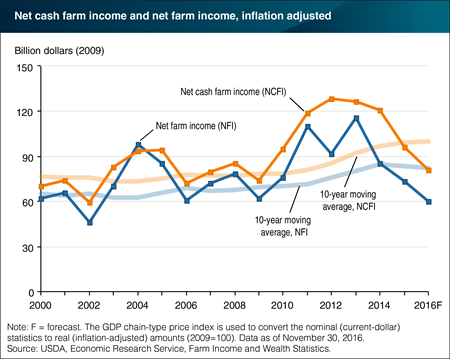

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

Net cash farm income and net farm income are two conventionally used and related measures of farm sector profitability. The first measure includes cash receipts, government payments, and other farm-related cash income net of cash expenses, while the second is more comprehensive and incorporates noncash transactions such as implicit rents, changes in inventories, and economic depreciation. Following several years of high income, both measures have trended downward since 2013. ERS forecasts that net cash farm and net farm income for 2016 will be $90.1 billion and $66.9 billion, respectively, or $80.9 billion and $60.1 billion, respectively, when adjusted for inflation (in 2009 dollars). Cash receipts declined across a broad set of agricultural commodities in 2015, and are expected to fall further in 2016—primarily for animal/animal products. Production expenses are forecast to contract in 2016, but not enough to offset the commodity price declines. Net cash farm and net farm income are below their 10-year averages, which include surging crop and animal/animal product cash receipts from 2010 to 2013. Find additional information and analysis in ERS’ Farm Sector Income and Finances topic page, updated November 30, 2016.