Advancements in Apple Picking: An Industry Addresses Tight Farm Labor Markets

- by Skyler Simnitt, Philip Martin and Marcelo Castillo

- 6/15/2023

Highlights

- Because apples can bruise easily and vary in how they ripen, growers rely more heavily on manual labor than on machines during harvest.

- A dependence on hired workers means labor is among the biggest expenses for U.S. apple growers, accounting for up to one-fourth of production costs.

- The United States is a major producer and exporter of apples, led by orchards in the State of Washington. Domestically grown apples account for more than 90 percent of availability in the United States.

- Apple growers use machines to increase worker productivity.

Apples are a versatile fruit. They store well and thrive in temperate climates like that of the United States, which ranks second in the world in apple production. However, apples also bruise easily, so most tree fruit mechanical harvesters are simply too rough on the fruit. To prevent bruising and ensure farmers can harvest their crop at its peak, apples intended for sale in fresh markets are picked by hand. Consequently, labor is among the biggest expenses for U.S. apple growers, accounting for up to a fourth of production costs.

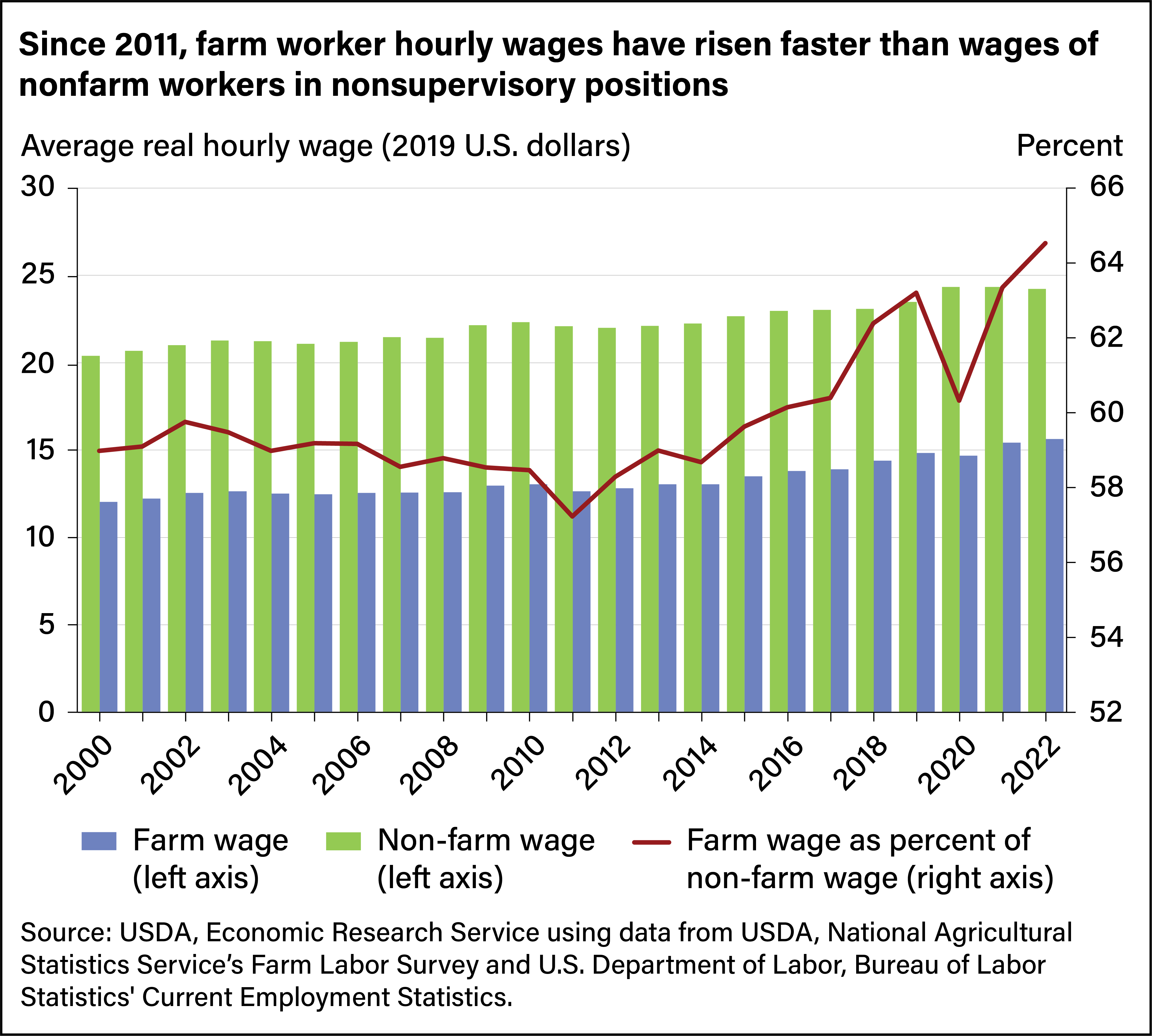

With its reliance on hired labor, the U.S. apple industry is especially sensitive to rising labor costs and constraints in the supply of farm workers. As farm labor markets tighten, hiring people to work in orchards, especially at harvest time, becomes more costly. Growth in the hourly wage rate for farm labor has been outpacing that of nonagricultural production workers. In addition, the H-2A agricultural guest worker program, a Federal visa program that allows U.S. agricultural employers to bring in foreign workers on seasonal contracts, continues to expand. In the last decade, the number of H-2A positions certified by the U.S. Department of Labor increased fourfold. To adjust to changing labor markets, to remain profitable, and to maintain high production levels, U.S. apple growers are updating their cultivation and harvest practices.

United States Is a Major Producer and Exporter of Apples

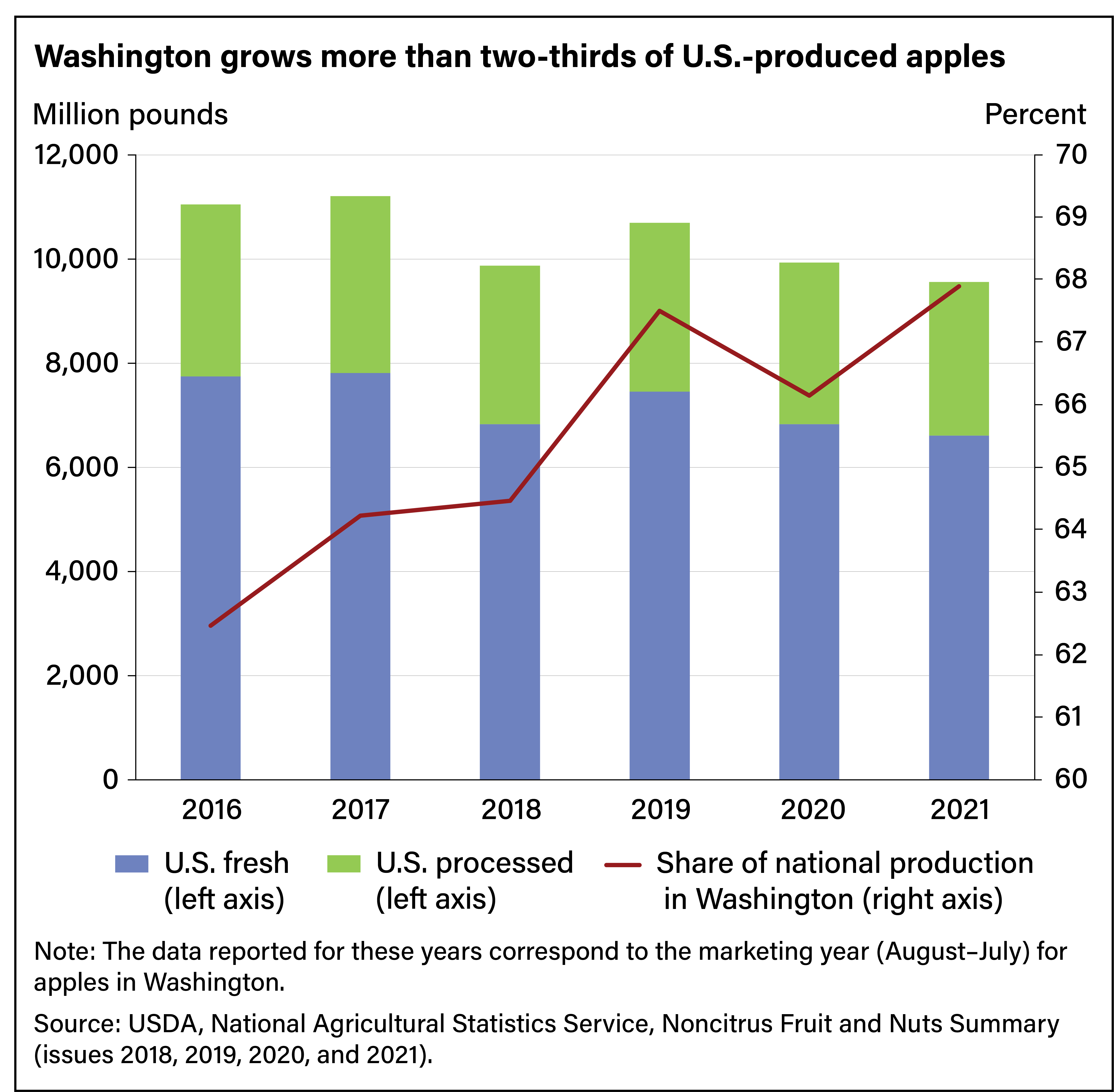

In the marketing year (August–July) period from 2019/20 to 2021/22, the United States produced an average of 10.1 million pounds of apples, 6.9 million of which were for the fresh market. Throughout this period, U.S.-grown apples accounted for an average of 96 percent of fresh market apple availability in the United States, an unusual share of consumption among specialty crops. The United States also is a major exporter of apples, with fresh market exports increasing 24 percent over the last 20 years. By the 2021/22 marketing year, 23 percent of the U.S. fresh apple supply, by weight, went to exports—nearly half of which went to Canada and Mexico.

The State of Washington leads the country in apple production, accounting for about 68 percent of U.S. production, by weight, in 2021. Washington’s sizeable production and proximity to Canada and Asia-Pacific markets make that State’s apples an important source of exportable supplies. About 75 percent of the apples grown in Washington are intended for sale in the fresh market, and the rest are used to make juice, cider, dried apples, and other processed products. Other prominent apple-producing States are Michigan (12 percent) and New York (10 percent).

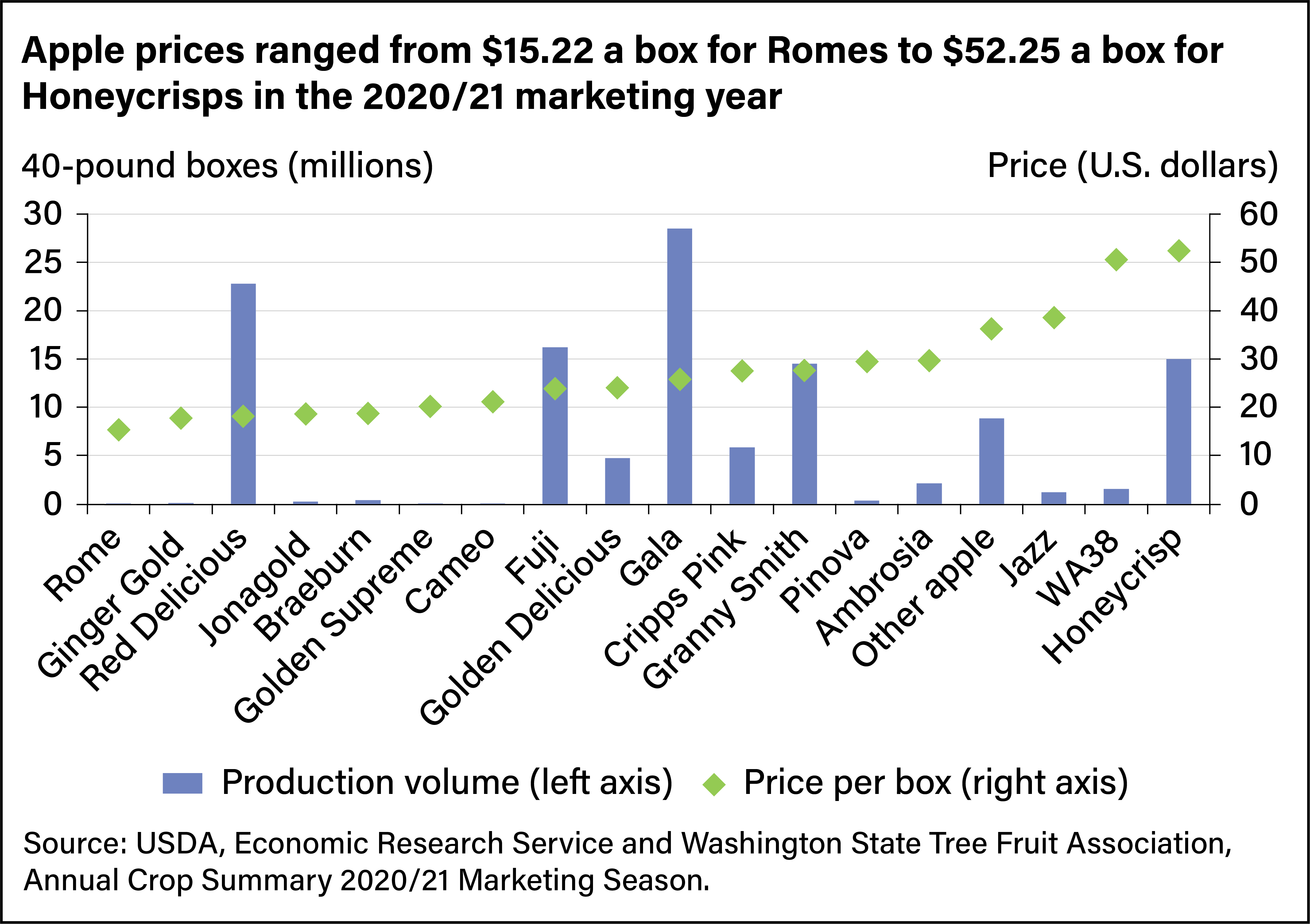

Commercially grown apple varieties encompass a range of attributes, including texture, taste, and skin color. The Washington State Tree Fruit Association collects and publishes shipment data for about 20 apple varieties. Red Delicious accounted for nearly half of apples shipped from the State during the 2000/01 marketing year, although that share fell in subsequent years. Over the last two decades, varieties such as Gala, Fuji, Granny Smith, and Honeycrisp have gained popularity among consumers.

Apple varieties require different cultivation and harvest methods, so production-related labor expenses also vary. Red Delicious apples ripen uniformly and are usually harvested with a single pass through the orchard. That makes them the easiest and least expensive variety to harvest. Conversely, Honeycrisp apples do not ripen all at one time, so they require up to five passes through the orchard. In 2019, labor costs for Honeycrisp apples accounted for 27.9 percent of growers’ overall costs, according to production-cost studies of five apple varieties grown in Washington. Harvest costs as a percent of total labor costs ranged from 28.5 percent for Granny Smith apples to 34.8 percent for Honeycrisp. Harvest workers can be paid by the hour but are often paid piece rates instead. The average piece rate for apples picked in Washington ranged from $20 to $28 a bin in 2021. By increasing individual productivity, workers compensated on a piece rate payment scheme can potentially earn more than they would at a set hourly wage rate. During the 2021 season, for example, apple pickers in the State of Washington on a piece rate compensation scheme earned between $16 to $18 dollars an hour, about 20 percent more than the State’s minimum wage of $13.69, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

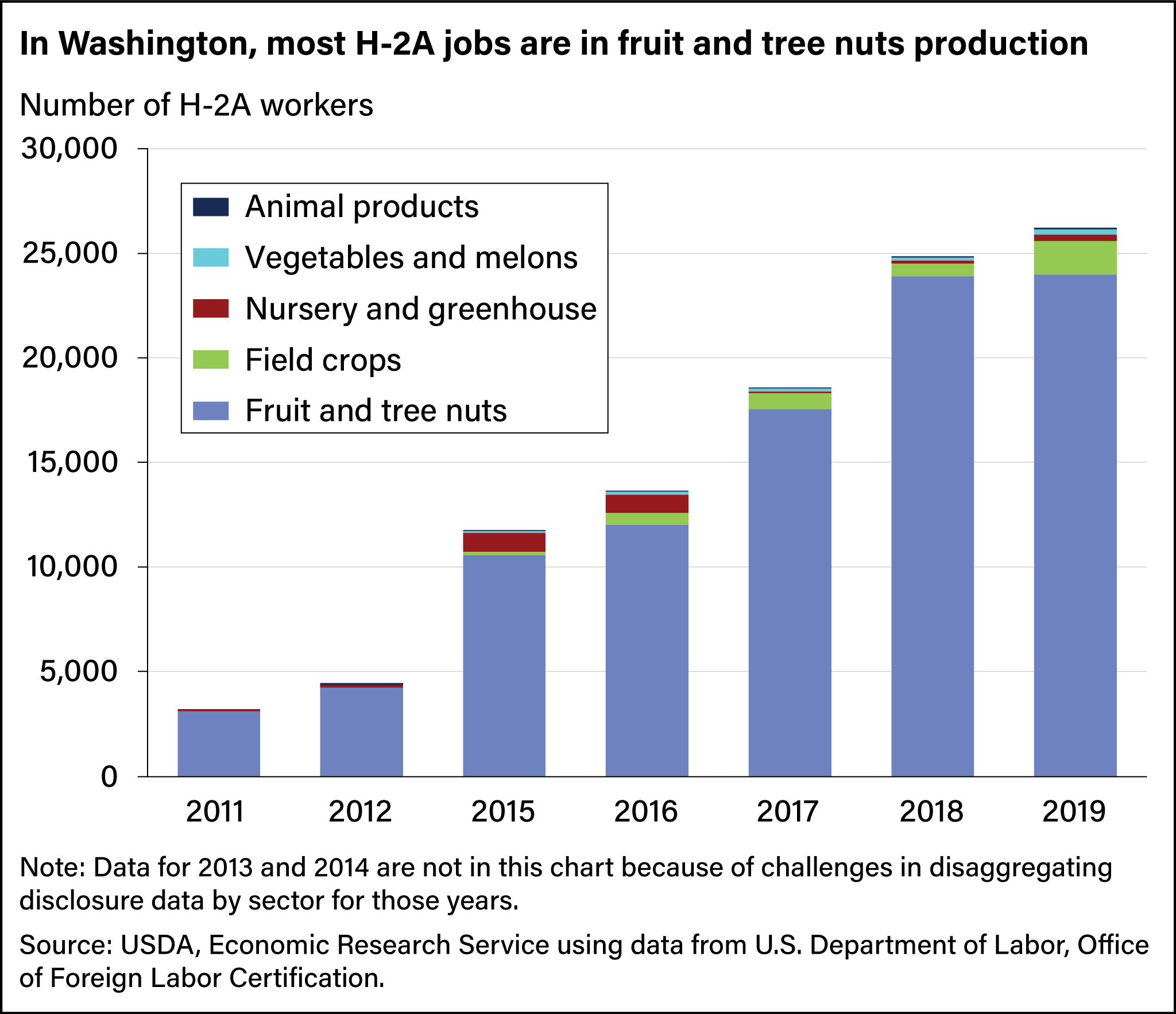

Guest Workers on H-2A Visas Are Key Source of Labor for Washington Growers

Washington fruit growers increasingly employ guest workers through the H-2A visa program to meet their labor needs. The H-2A visa program permits U.S. agricultural employers to bring in foreign workers on contracts that typically last less than a year. Since the program’s inception in 1986, use of H-2A historically has been highest in the Southeast, especially in North Carolina, Florida, and Georgia. However, as the Nation’s top apple-producing State, Washington also is among the biggest users of H-2A, with the total number of positions certified coming in fourth after Florida, California, and Georgia, as of 2022. The U.S. Department of Labor releases detailed disclosure data on H-2A employers. These data report, among other things, the primary tasks or crops for which the employers need H-2A workers. ERS researchers analyzed these data, placing each position certified within one of five main agricultural sectors: fruit and tree nuts, field crops, nursery and greenhouse, vegetables and melons, and animal products. H-2A positions certified within the fruit and tree nuts sector dominate in Washington, accounting for up to 96 percent of the positions certified. According to the Labor Department disclosure data, 4,857 positions were certified for work in apples in 2019, while 5,943 were certified for the generic position of general farm work, which may include apple workers among other fruit crops. Data on apple labor in Washington are scarce, but an estimated 40,000 to 50,000 seasonal apple workers are employed in that State each year.

Mechanical Aids Increase Worker Productivity in Apple Orchards

To remain competitive amid rising labor costs, fruit and vegetable growers are finding ways to substitute human labor with machines that can help workers become more productive, harvest more fruit in a shorter time, and reduce the number of workers needed. However, it is easier to mechanize the harvest of some crops than others. Growers already are using harvest machines for the types of produce that are easiest to mechanize, such as blueberries, raisin grapes, and baby leaf lettuce. It is hardest to mechanize the harvest of fruits and vegetables that bruise easily or do not ripen uniformly, or for which there are relatively few producers. The most difficult crops in this category include strawberries, table grapes, fresh market tomatoes, and melons. Fresh-market apples fall in the middle of the spectrum.

For centuries, apple pickers have carried, placed, and climbed ladders to reach hard-to-access fruit. From the ladders, pickers must carefully place apples into bags or buckets that hang over their shoulders and empty their full bags into bins—receiving credit for each bin picked. Working from ladders in orchards on uneven ground can be dangerous, and workers spend up to a third of their time moving and positioning ladders rather than picking. To address this issue, many Washington apple growers use platforms that travel mechanically between tree rows and lift workers securely and quickly up to fruit level. These platforms may be self-driving or pulled by a tractor. The use of apple-picking platforms accelerated after 2005, and by 2010 about 11 percent of growers were using them. Platforms also were used for non-harvest tasks such as pruning trees and placing trellises. Newer orchards include specially trained trees grown on dwarf rootstock and supported by trellises, allowing workers to spend less time reaching through trees. Another benefit is that these trees can use more energy to produce apples, resulting in higher yields and earlier production.

In 2000, the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission provided a roadmap to promote the development of mechanical aids. Commission-supported research contributed to the development of harvest platforms and selective harvest machines. Nonselective harvest machines aim to cover the entire crop on a single pass, but selective harvest machines target only mature product on a given pass without disturbing the unripe fruit. The goal is to imitate human vision and dexterity for choosing and picking ripe fruit. Selective harvest machines are in development, following the tree fruit commission’s initial investment. Apples grown on trellis systems are more amenable to these harvest technologies, reducing the time and distance needed to locate ripe fruit and pick it with a robot arm.

This article is drawn from:

- Calvin, L., Martin, P. & Simnitt, S. (2022). Adjusting to Higher Labor Costs in Selected U.S. Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Industries. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-235.

- Calvin, L., Martin, P. & Simnitt, S. (2022). Supplement to Adjusting to Higher Labor Costs in Selected U.S. Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Industries: Case Studies. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. AP-103.

You may also like:

- Simnitt, S. & Martin, P. (2022, December 28). U.S. Fruit and Vegetable Industries Try To Cope With Rising Labor Costs. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Farm Labor. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Castillo, M., Simnitt, S., Astill, G. & Minor, T. (2021). Examining the Growth in Seasonal Agricultural H-2A Labor. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-226.

- Galinato, S. & Gallard, K. (2020). 2019 Cost Estimates of Establishing, Producing, and Packing Cripps Pink Apples in Washington. Washington State University Extension.

- Galinato, S. & Gallard, K. (2020). 2019 Cost Estimates of Establishing, Producing, and Packing Honeycrisp Apples in Washington State. Washington State University Extension.

- Galinato, S. & Gallard, K. (2020). 2019 Cost Estimates of Establishing, Producing, and Packing Fuji Apples in Washington State. Washington State University Extension.

- Galinato, S. & Gallard. K. (2020). 2019 Cost Estimates of Establishing, Producing, and Packing Granny Smith Apples in Washington State. Washington State University Extension.

- Gallardo, K. & Brady, M. (2015). Adoption of Labor-Enhancing Technologies by the Specialty Crop Agriculture: The Case of the Washington Apple Industry. Agricultural Finance Review.

- H-2A Temporary Agricultural Labor Certification Program—Selected Statistics, Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 EOY. (2021). U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Office of Foreign Labor Certification.

- Foreign Labor Certification Annual Report. (2016). U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Office of Foreign Labor Certification.