Specialized Stores Serving Participants in USDA’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Can Reduce Program Food Costs and Increase Food Store Access

- by Patrick W. McLaughlin and Stephen Martinez

- 3/1/2021

Highlights

- “Above-50-percent” (A50) stores derive the majority of their food sales from redeeming benefits from USDA’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) participants.

- Research on A50 stores in California suggests the existence of A50 stores in Greater Los Angeles expanded participant access to stores authorized to accept WIC benefits without raising program food costs.

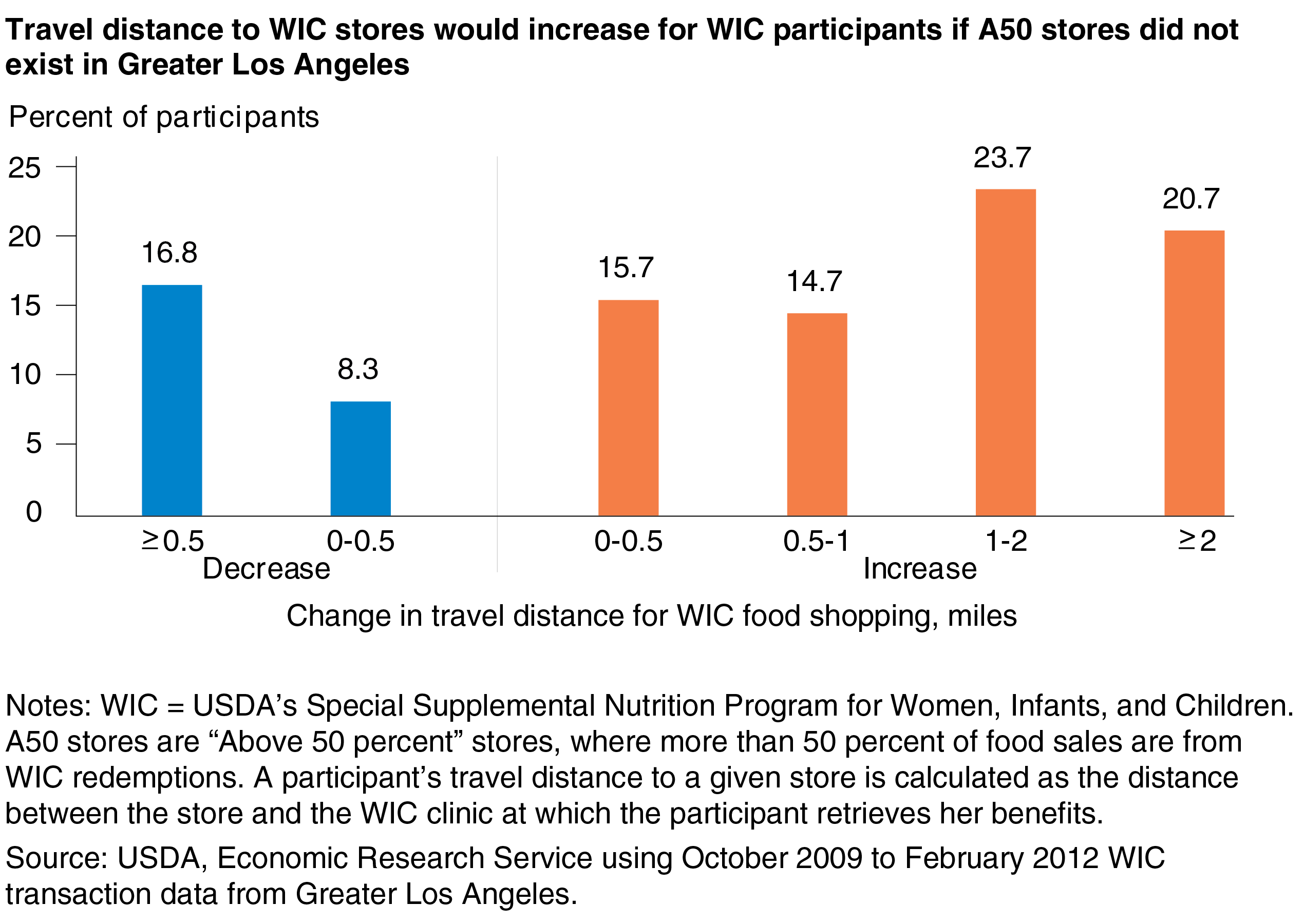

- Without A50 stores in Greater Los Angeles, researchers estimated that 21 percent of WIC participants who do most of their WIC shopping at these stores would have traveled 2 or more additional miles to shop for food based on their WIC shopping history.

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is USDA’s third-largest food assistance program. The program provides supplemental foods, nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and healthcare referrals at no charge to low-income and nutritionally at-risk pregnant and postpartum women, as well as infants and children up to age 5. WIC is administered by USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), with substantial operational control of the program delegated to State agencies. In 2019, 6.4 million people participated in WIC; Federal spending for the program totaled $5.2 billion.

In most States, participants obtain the supplemental foods at stores authorized by WIC State agencies to accept WIC food benefits. Most WIC-authorized stores are typical food retailers such as supermarkets, large grocery stores, and supercenters for which WIC redemptions constitute a small share of total food sales. However, some WIC State agencies authorize stores whose food business is mostly focused on accepting WIC benefits.

Particularly, some stores are “above-50-percent” (A50) stores, which derive more than 50 percent of their food sales from WIC redemptions. A50 stores must adhere to additional pricing regulations, which adds administrative burden for both the WIC State agency and the store. However, A50 stores are more convenient for some WIC shoppers because they specialize in offering WIC-approved foods and serving WIC participants. Recent studies by USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) and collaborators found that A50 stores in Greater Los Angeles appeared to decrease travel distances to WIC stores to redeem benefits without raising program costs.

WIC Foods Tailored to Participants’ Nutritional Needs

WIC provides participants with monthly food packages that are designed to supplement participants’ diets with needed nutrients. Most of the food packages contain fixed amounts of specific food products. For example, the monthly food package for a woman fully breastfeeding her infant provides up to 144 fluid ounces of 100-percent fruit or vegetable juice, 24 quarts of low-fat milk, 1 pound of cheese, 2 dozen eggs, 1 pound of whole-wheat bread, 30 ounces of canned fish, and 1 pound of dried legumes or 18 ounces of peanut butter. Her 8-month-old infant’s monthly food package includes 24 ounces of infant cereal, 256 ounces of prepared infant fruits and vegetables, and 77.5 ounces of infant meats. In addition to providing pre-set quantities for some foods, WIC provides a cash value benefit for fresh, canned, and/or frozen fruits and vegetables, and WIC participants choose the amount of fruits and vegetables they will buy up to the total value of the benefit.

In general, most WIC participants obtain the supplemental foods by redeeming the prescribed quantities —dollar values in the case of fruits and vegetables—using an Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) card (or paper vouchers prior to 2020) at WIC-authorized stores. In many cases, WIC participants can choose any brand or package size allowed by the WIC State agency, although sometimes participants are required to buy the least expensive or store brand among eligible food items.

A50 Stores Provide Benefits for Some WIC Participants

WIC State agencies have substantial latitude in choosing the types of retailers authorized to accept WIC benefits. WIC-authorized stores may be large grocers, supermarkets, and supercenters such as Walmart or Target, medium-sized grocers, or small retailers such as convenience and drug stores. WIC State agencies reimburse retailers for the foods redeemed by WIC participants based on the prices charged by the retailer for the WIC foods up to certain limits established by each State agency. These limits vary by store type or “peer group.” The prices charged by stores of different peer groups can affect food costs associated with the WIC program. FNS regulations require States to categorize authorized stores into peer groups based on factors that affect store prices, such as store size and location, and to set allowable reimbursement levels for each peer group.

Almost all WIC State agencies authorize large retailers, while some authorize medium, small, and non-traditional food retailers, such as convenience stores and pharmacies. When processing applications for authorized stores, State agencies may face a tradeoff between sufficiently containing costs for WIC foods and ensuring participants’ access to WIC stores, although State agencies are required to do both. Large food retailers are expected to have lower prices for WIC food items compared with small food retailers.

However, not all WIC participants live near large stores, and if they do, they may prefer other options for WIC shopping. Small retailers, such as convenience and corner stores, may provide critical access to some WIC participants. Generally, small retail stores are more likely to charge higher prices than large retailers. Small stores often lack the procurement networks of large retailers that lower per unit selling costs and, in turn, prices charged to customers. A 2018 study of California WIC-authorized stores found that small WIC stores with relatively few nearby competing WIC-authorized stores—and thus more critical in providing food access—were more likely to have higher prices than small stores with more competition among WIC stores.

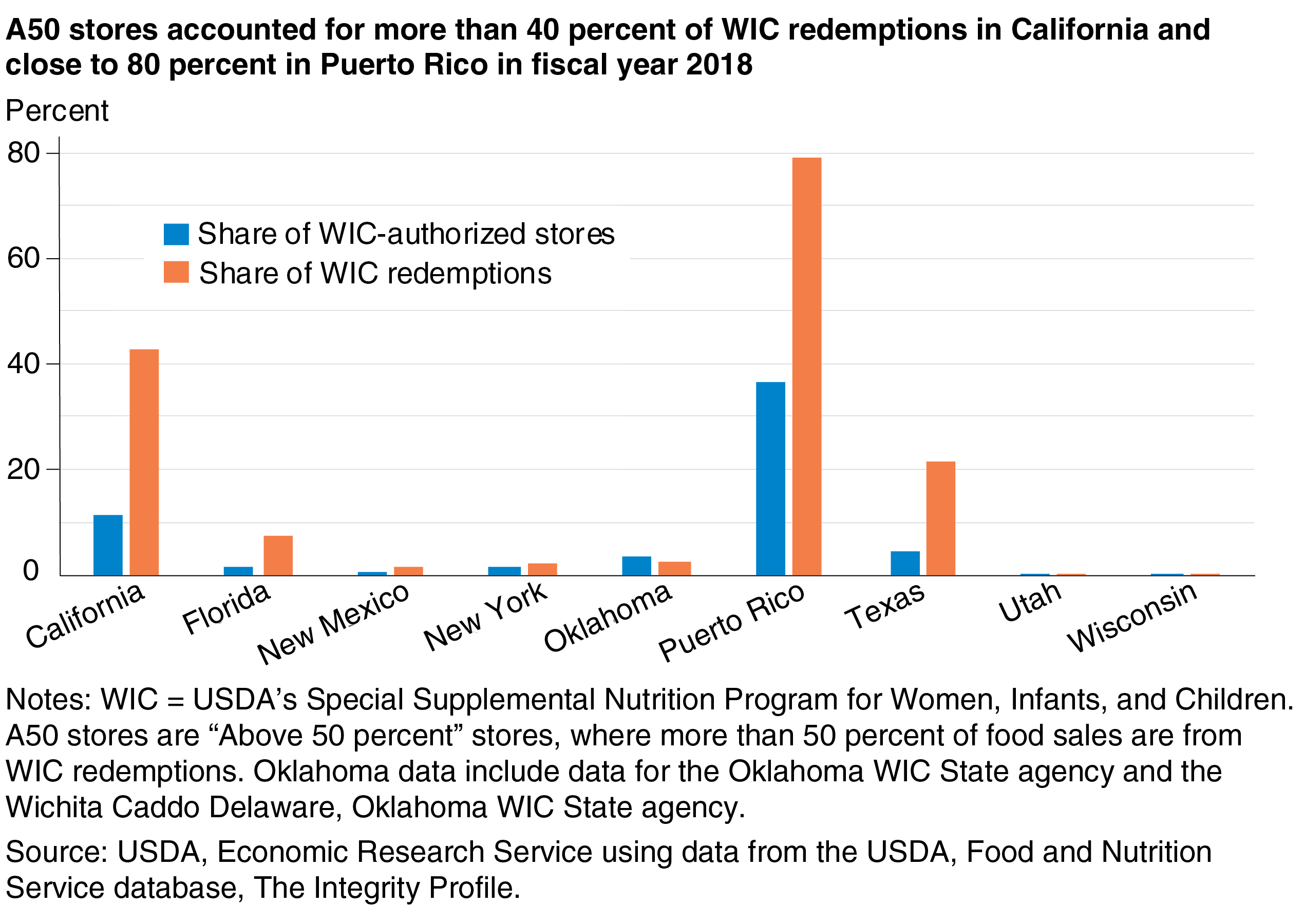

Some States authorize A50 stores that, as mentioned above, obtain more than 50 percent of their food sales from WIC. Over the last decade, the total number of A50 stores in the United States and U.S. territories has fallen from 1,401 stores in 2008 to 973 stores in 2018. Although the 973 A50 stores in 2018 represented just 2.2 percent of WIC stores nationwide, they accounted for 10.6 percent of national WIC redemptions.

The business structure of A50 stores is diverse: Some may be independent operators for whom redeeming WIC benefits is not the primary business, while others may be organized into chains that exist to only serve WIC participants. For example, some A50 stores may be variety stores with large non-food offerings (such as a “dollar store”) that happen to have a majority of food sales from WIC transactions. Other A50 stores’ primary business model focuses on redeeming WIC benefits. In either case, the variety of foods sold generally is less than a typical supermarket, so WIC participants must visit other stores for their total food and grocery needs.

A50 stores, however, can offer advantages for WIC participants over traditional food retailers by making WIC-approved products easy to locate and emphasizing convenient checkout with cashiers who are familiar with handling WIC transactions. Redeeming WIC vouchers in supermarkets can be time-consuming and stressful for participants and cashiers when they are in long checkout lines filled with primarily non-WIC participants. The homepage of one leading national A50 chain tries to appeal to customers looking for a different experience by emphasizing “no long grocery lines” and that many of the chain’s employees “at one time participated in the Women, Infants, and Children Program.”

A50 Stores Present Administrative Challenges for WIC State Agencies, USDA

Because WIC benefits must be used only to purchase WIC-approved items irrespective of price in most cases, WIC-authorized stores may face an economic incentive to increase prices of certain items that are commonly bought by WIC participants but less so by other customers. This economic incentive is especially strong for A50 stores because almost all purchases will be made by WIC participants. To contain food costs, FNS regulations state that the average value of WIC State agency reimbursements paid to A50 stores for WIC benefits cannot exceed the average reimbursement paid to non-A50 stores operating in the same State. In effect, WIC State agencies set a price ceiling on what A50 stores can charge for WIC foods, with the ceiling set at the statewide average price charged at non-A50 WIC stores in the State.

There are additional administrative requirements for WIC State agencies that authorize A50 stores. For example, agencies are required to implement procedures to limit the types and dollar values of incentives that A50 stores can provide to participants to encourage their patronage. In 2018, only 10 WIC State agencies authorized any type of A50 store—less than half the number of States and Indian Tribal Organizations that did so in 2008. WIC State agencies may be reluctant to authorize A50 stores because of the additional regulatory requirements and associated administrative burdens to ensure program integrity and cost containment.

California’s A50 Stores Reduce Shopping Distances for WIC Participants Without Raising WIC Food Costs

Of the just under 1,000 A50 stores operating in the United States and U.S. territories in 2018, 493 were in California. Other States and U.S. territories with relatively high numbers of A50 stores are Texas (103 stores), Oklahoma (18 stores), and Puerto Rico (276 stores). A50 stores accounted for 42.6 percent of California’s WIC redemptions in 2018. Comparatively, A50 stores accounted for 21.5 percent of WIC redemptions in Texas, 2.2 percent in Oklahoma, and 78.9 percent in Puerto Rico.

California authorizes a wide variety of retailer types to accept WIC benefits. These include supermarkets, supercenters with a grocery component (e.g., Walmart), small and medium-sized grocery stores, and convenience-type stores, as well as A50 stores. In California, A50 stores are often near WIC clinics, which puts the stores close to WIC participants and enhances access.

ERS researchers and collaborators conducted several recent studies using administrative data on WIC transactions in the Greater Los Angeles area during 2009-2013. These studies address the economics of private retailers serving WIC, including food prices, cost containment, and participant access to WIC stores. The researchers address, in part, the following hypothetical question: If A50 stores had not been authorized in the State, what would be the food costs and participants’ travel distances to the nearest WIC-approved store? The researchers developed a model that simulates WIC shopping behavior under the assumption that WIC vouchers redeemed at A50 stores were “reassigned” to the most plausible non-A50 store.

At the time of the studies, each California WIC-approved store was classified into a peer group based on size (determined by the number of cash registers) and geographic location within the State. The WIC State agency sets maximum reimbursement levels for WIC vouchers that varied by peer group. Generally, small stores with fewer cash registers had higher reimbursement levels because they charge higher prices, likely in part to offset their inability to command lower wholesale prices for the foods they sell.

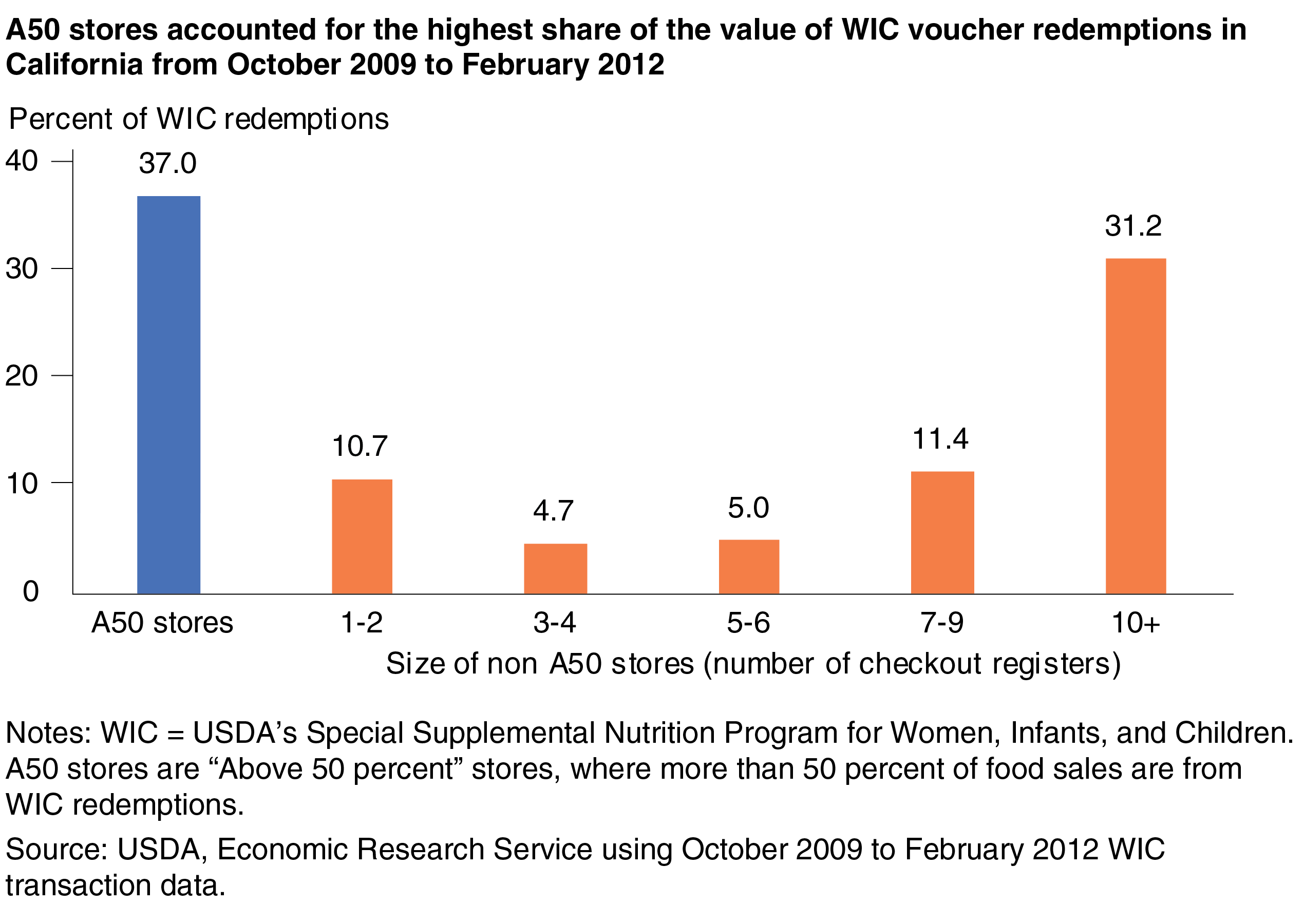

During the period from October 2009 to February 2012, A50 stores in California collected the greatest share of WIC redemptions compared with any other store type, based on peer group. A50 stores accounted for 37 percent of the value of redeemed WIC vouchers, followed by 31 percent at non-A50 stores with 10 or more cash registers—the largest store size category.

Results from the simulation suggest the presence of A50 stores in Greater Los Angeles modestly lowered WIC costs compared with a world without them. During the study period, the FNS-mandated reimbursement ceiling for A50 stores was lower—often considerably—than the reimbursement ceiling for any other non-A50 peer group in the State. If A50 stores were removed, reimbursements paid to WIC stores in the Greater Los Angeles area would increase by an estimated 1.2 to 1.7 percent (depending on the specific food benefit). This hypothetical change would raise WIC food costs cumulatively over the study period by $3.5 million to $4.9 million. This increase would occur primarily from 7 to 8 percent of vouchers going to small stores in accordance with the past shopping behavior of WIC participants. Many of these small stores were relatively isolated but had a large WIC customer base, and the simulation predicts higher prices without the competition of A50 stores. For example, without A50 stores, the average cost of the voucher containing a combination of low-fat milk, whole-grain bread, and cereal at small stores is $23.63, compared with $16.18 when A50 stores are included. Infant formula costs rise from $17.48 with A50 stores present to $25.73 at small stores when A50 stores are absent.

The researchers also examined the implications for participant access in Greater Los Angeles over the 2009-2012 period. Lacking information on the home addresses, the study did not measure the distance that WIC participants travel from home to a WIC-authorized store. As a proxy, the study used distances from a WIC clinic to an A50 store or its nearest competitor (if A50 stores hypothetically disappeared). The average distance from a Greater Los Angeles A50 store to the nearest WIC clinic is 1.1 miles, compared with about 2 miles for non-A50 stores. About 6 percent of A50 stores are located essentially next to the nearest clinic, and 28 percent are located within one-quarter of a mile. Results from the simulation model used found that distance traveled to a WIC store would increase if A50 stores no longer existed. Average one-way travel distances across all WIC participants in Greater Los Angeles increased modestly from 2.2-2.3 miles to 2.5-2.8 miles. Among A50 shoppers who conduct half or more of their WIC shopping at A50 stores, nearly 25 percent traveled 1-2 miles farther, while 21 percent traveled 2 or more miles farther in a world without A50s.

WIC Participants Loyal to A50 Stores

Based on the average WIC participant in the Greater Los Angeles area, A50 stores are 4 to 5 percent more likely to see returning participants within 1 month than large foodstores. This suggests that despite the variety and lower prices for non-WIC shopping afforded at large stores, WIC customers were more loyal to A50 stores. Stores with higher customer loyalty likely provide a better WIC shopping experience.

From October 2009 to February 2012, many new A50 stores opened alongside existing A50 vendors in Greater Los Angeles. While existing A50 stores experienced slightly lower long-term customer retention than large foodstores, new A50 stores’ customer retention was significantly higher in their first 6 months of business and, per the above, maintained a high degree of loyalty among often returning customers. A50 entrants also experienced a high degree of month-to-month customer loyalty compared to large foodstores.

The research found that A50 stores increased access to WIC stores in Greater Los Angeles without imposing additional food costs on WIC. Assuming distance from a WIC clinic is reflective of their travel distance to WIC stores, most of the WIC participants in the simulation would have faced substantially longer distances to a foodstore had A50 stores not operated in California. A50 stores—including those recently authorized by the program or located near large foodstores—also enjoyed levels of WIC customer loyalty comparable with large foodstores. These findings indicate that A50 stores were a preferred outlet for WIC shopping by many participants.

This article is drawn from:

- Volpe, R. (2021). Cost Containment and Participant Access in USDA's Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): Evidence from the Greater Los Angeles, CA, Area. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-283.

- "The Economics of Food Vendors Specialized to Serving the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program". (2018). American Journal of Agricultural Economics. Vol. 101, No. 1, 20-38.

You may also like:

- Tiehen, L. & Frazão, E. (2016). Where Do WIC Participants Redeem Their Food Benefits? An Analysis of WIC Food Dollar Redemption Patterns by Store Type. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-152.