Southeast Asia’s Growing Meat Demand and Its Implications for Feedstuffs Imports

- by Tani Lee and James Hansen

- 4/1/2019

Highlights

- Southeast Asia’s expanding population and increasing incomes, urbanization, and retail sectors are contributing to rising meat consumption and growing imports of feedstuffs.

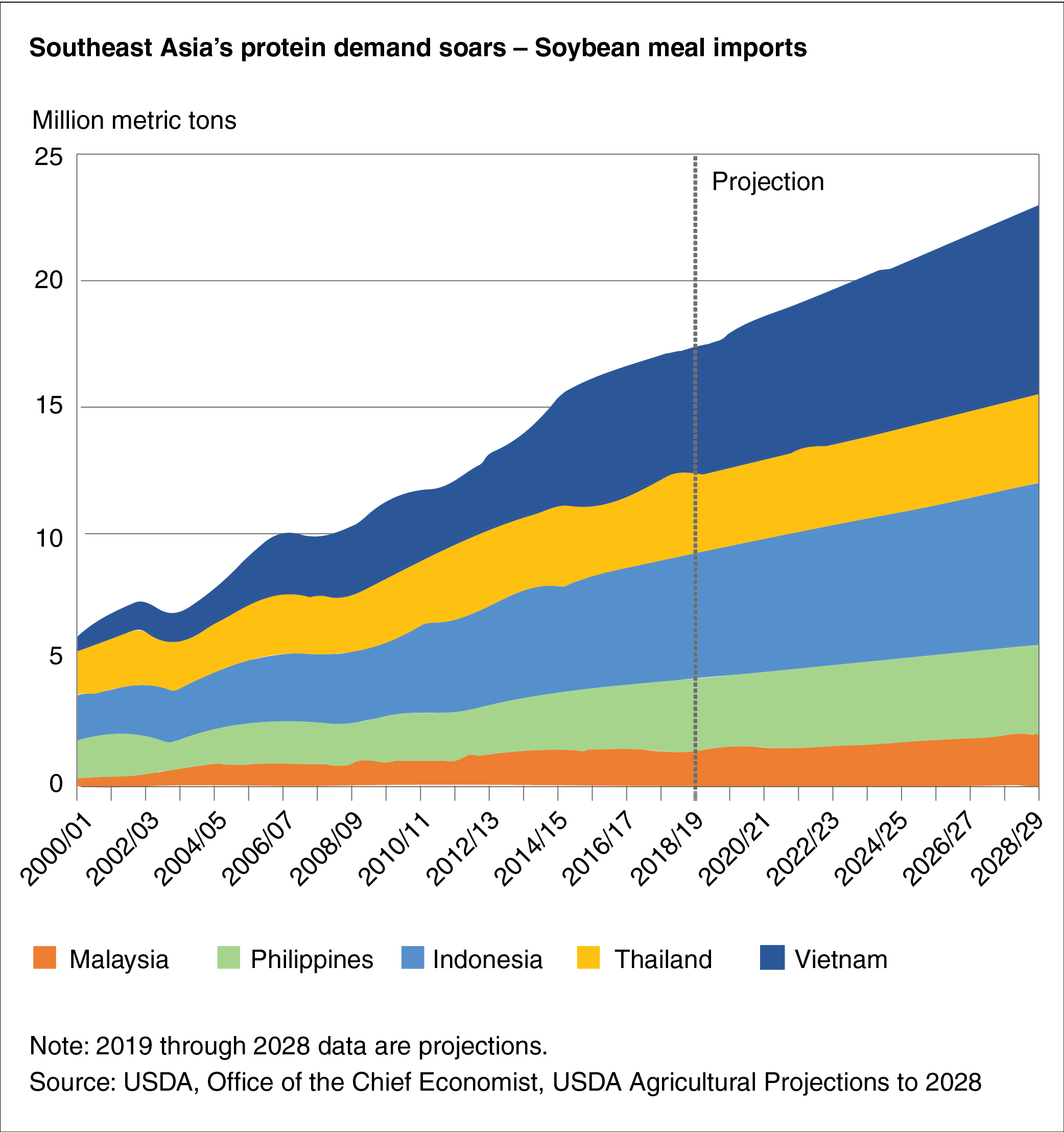

- Over the next decade, the region is projected to become the fastest growing importer of soybean meal—typically used in livestock feed—and surpass the European Union as the largest importer by 2022. Increasing poultry and pork consumption and production are driving the rise in soybean meal imports, along with the region’s limited capacity to crush whole soybeans.

- The region must also supply its rapidly growing pork and poultry operations with feed grains such as corn and feed-quality wheat. To support domestic corn production, however, some countries, including Indonesia and the Philippines, restrict imports by limiting import permits and imposing tariff-rate quotas. This has led to increasing imports of alternative feed sources such as feed-quality wheat and distillers’ dried grains with solubles (DDGS).

Southeast Asia’s rising incomes, growing population, and increasing urbanization have contributed to growth in livestock production and meat consumption, particularly poultry and pork. Southeast Asia includes 10 countries: Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. This article focuses on five key emerging markets within the region: Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam (5 Southeast Asian Countries). According to USDA’s International Long-Term Projections to 2028, the region will become the world’s fastest-growing importer of soybean meal—a key ingredient in animal feed—over the next decade and will overtake the European Union (EU) as the largest soybean meal importer by 2022. In addition to its expanding pork and poultry production, the region’s growing imports of soybean meal are driven by its limited soybean crushing facilities. There are growing concerns about recent confirmed cases of African Swine Fever (ASF) expanding into Southeast Asia, which will likely curb expansion and potentially limit imports for feedstuffs. However, ASF was not an issue in the region during the development of the most recent commodity projections in October 2018.

The region’s feed grain demand and imports are also rapidly increasing. Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia are among the region’s fastest growing corn-importing countries. To support their domestic corn producers, however, Indonesia has limited corn import permits and the Philippines has imposed a tariff-rate quota (TRQ) on corn imports. TRQs and non-tariff measures like import-permit limits usually have a chilling effect on imports. As the region is unable to expand its domestic wheat production to meet its feed and food demands, some countries with corn-import restrictions have expanded imports of feed-quality wheat. Additionally, Southeast Asia has increased imports of dried distillers’ grains with solubles (DDGS)—a coproduct of ethanol production—as an alternative energy and protein source in animal feed.

Southeast Asia’s Population and Income on a Growth Path

As with most emerging markets, Southeast Asia’s population, urbanization, and income continue to expand. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Census, the region’s 10 countries total population grew 11.6 percent from 2008 to 2017, reaching 665 million in 2017, and is expected to grow to 720 million by 2027.

According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) data on urban and rural population, Southeast Asia’s 10 countries have exhibited strong growth in urbanization. In 2000, rural and urban population were 62 percent and 38 percent, respectively. By 2017, rural population declined to 51 percent, and urban population is now 49 percent of the total population. Over the past 10 years, rural population has been stable, while urban population increased by 32 percent. The urban population is expected to increase by 24 percent rising through 2028, reaching 55 percent of the population while the rural population declines by 3 percent to 45 percent of the population.

The region’s per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has grown by an annual rate of 3.4 percent over the last decade and is projected to grow slightly faster, at 3.5 percent annually, over the next decade. (In comparison, the U.S. GDP per capita annual growth rate was 0.7 percent from 2008 to 2017 and is projected to grow 1.3 percent annually over the next decade.) Malaysia, Southeast Asia’s third wealthiest country after Singapore and Brunei, had per capita GDP at $11,453 in 2017, nearly double that of Thailand, , followed by Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. However, Vietnam had the fastest per capita GDP growth rate from 2008 to 2017 at 4.4 percent.

As Income Grows in Southeast Asia, Meat Consumption and Production Expand

As the region’s incomes rise, meat consumption also increases, although fish and seafood are the largest meat sources consumed and produced—and are partially responsible for feedstuffs demand. Every Southeast Asian country has different meat preferences, as reflected by their levels of consumption and production. Beef and dairy production is quite small and has little impact on feed demand. Water buffalo is produced in some rural areas, but they are not fed modern feed rations. Some countries, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, prefer poultry, while others prefer pork. Vietnam is the second-largest producer and consumer of pork in Asia after China and the sixth-largest producer of pork in the world. All the region’s nations are projected to increase their consumption and production of pork and poultry over the next decade.

Southeast Asia’s pork and poultry production projections

Southeast Asia’s poultry production expanded by 56 percent in the last decade, growing from 5.9 million metric tons (mmt) to 9.2 mmt in 2018, and is expected to reach 12.3 mmt by 2028. The growth in the region’s pork production was slower; it increased 23 percent from 2009 to 2018 and is expected to rise 21 percent by 2028. The pace could be attributed to the region’s overall preference for poultry over pork, as most Southeast Asian countries produce much more poultry.

Vietnam’s hog and poultry production has grown the fastest compared to the rest of the region, and the country is projected to continue to be Southeast Asia’s largest producer of pork into the next decade, reaching 3.3 million mmt by 2028. Indonesia is the largest egg producer and is projected to continue as the largest producer over the next decade, with 2.2 mmt expected to be produced in 2028.

Thailand is the world’s fourth-largest poultry exporter behind Brazil, the United States, and the EU. With improved production facilities and food safety practices, exports are expanding. Roughly 70 percent of the poultry it exports is in the form of cooked poultry products. Major export markets include Japan, the EU, and Korea. Thailand’s poultry exports are projected to rise 59 percent from 2018 to reach 1.35 million tons by 2028.

Soybeans and Soybean Meal Production, Use, and Trade

Southeast Asia’s soybean meal imports make up a much larger share of its imports than do whole soybeans because of the limited number and capacity of soybean crushing facilities in this region.

Imports of soybean meal feed more than tripled from 2000 to 2018. The region is projected to account for 43 percent of the projected increase in world soybean meal trade by 2028. Soybean meal imports are projected to surpass EU imports in 2022, growing to 22.9 mmt by 2028. Argentina, the dominant global soybean meal supplier, is the largest supplier of soybean meal to Southeast Asia, followed by Brazil, the United States, and India. By 2028, Southeast Asia accounts for almost one-third of the global soybean meal import market share.

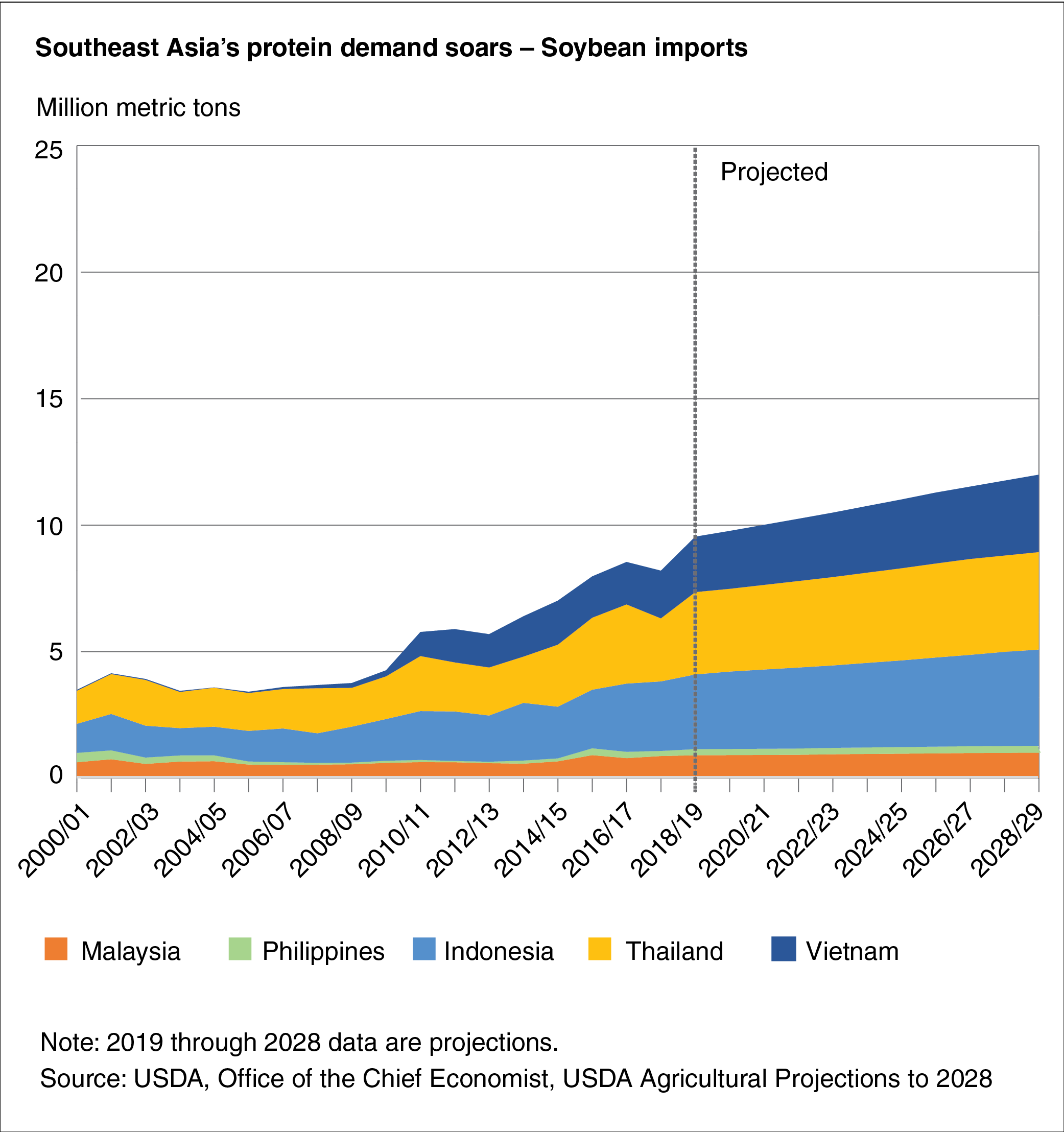

Despite the region’s constrained crushing capacity, whole soybean imports grew to 9.4 million tons in 2018 and are projected to increase to 11.9 million tons by 2028. Recent record global supplies of soybeans, as well as its competitive pricing, have encouraged many countries in the region, including Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, to add full fat (whole) soybeans to their feed mix. The United States is the leading supplier of soybeans to Southeast Asia, followed by Brazil.

Southeast Asia’s protein demand soars

Although Indonesia has the largest agricultural land area in the region, soybeans are a secondary crop and must compete with other commodities, such as mung beans. About 83 percent of soybeans consumed are imported. The Indonesian Government has also implemented policies promoting corn production over other crops. Almost all imported soybeans are used for food consumption, processed into tempeh and tofu by small-scale food processors, while only about 2 to 3 percent is used for feed. Because Indonesia has no crushing plants, it must import all of the soybean meal it uses for feed. Over 90 percent of Indonesia’s soybean meal is imported from Argentina and Brazil, whose prices have a competitive advantage over U.S. soybean meal.

Malaysia does not produce soybeans and must import its soybeans and meal. Roughly 80 percent of its imported soybeans are crushed into meal and oil, while the remaining 20 percent is identity preserved food use soybeans. Malaysia’s domestically crushed soybean meal is insufficient to meet its feed demand, so it must import meal to meet over 80 percent of its consumption needs.

Soybean meal production in the Philippines is limited, and with only one oilseed crushing facility, the country must import most of its soybeans and soybean meal for its hog and poultry industries.

Thailand’s soybean production is minimal, supplying only 2 percent of consumption, and the country mostly imports soybean and soybean meal for feed use. Its domestic production is mainly used for food. Thailand controls its trade of soybean and meal through tariff-rate quotas on imports and has restricted exports through bans imposed at various times. Most recently, the Government lifted its soybean meal export ban in April 2016 in anticipation of the region’s growing soybean meal demand.

In Vietnam, soybean production competes with other more profitable crops such as fruits and vegetables. Domestic production is minimal and supplies roughly 4 percent of needs. Vietnam’s soybean imports are expected to rise by 33.8 percent, reaching 3 million tons by 2028 due to expanding crushing capacity. The country has two crushing facilities, one in the south and a recently built plant in the north. Despite these two facilities, Vietnam’s soybean meal demand continues to rely heavily on imports. Soybean meal imports supply over 80 percent of its growing soybean meal consumption.

Corn Production, Use, and Trade

Southeast Asia’s corn imports are projected to grow by 8.7 mmt between 2018/19 and 2028/29 to reach 22.9 by 2028/29. Most of the growth is driven by Vietnam and Malaysia, the fastest growing corn importing countries in the region. Argentina and Brazil are the leading suppliers of corn to the region, while the United States, Russia, and Thailand are residual suppliers.

Although Indonesia’s domestic corn production is unable to meet its feed demand, the Government limits corn and feed wheat imports to support domestic corn production. After 2014, Indonesia’s corn imports for feed use decreased as the Government began to provide farmers with seed and fertilizer subsidies, set minimum prices, and placed import restrictions on corn for feed use.

Malaysia produces almost no corn and relies exclusively on imports to meet the feed needs of its steadily growing poultry and egg industries. Brazil and Argentina supply 80 percent of the country’s corn imports, while the United States is a much smaller supplier. Malaysia is expected to import 4.8 mmt of corn by 2028.

Philippine corn imports are hampered by a tariff-rate quota and constitute only 8 percent of its total consumption. In 2018, the country’s corn production reached 8.2 million tons. Feed-quality wheat is also often used as a substitute for corn in livestock production.

Thailand’s domestic corn production is unable to meet its feed demand, and the Government provides incentives to encourage farmers to produce more corn. Thailand also maintains a TRQ on corn imports and provides direct payments to rice farmers who produce corn off-season. Most recently, the Government imposed import restrictions on feed-quality wheat. If feed mills would like to import feed-quality wheat, feed mills must purchase domestic corn at a guaranteed minimum price. Despite this domestic corn purchase requirement, Thailand’s corn production cannot meet its feed demand, so it must import corn, feed-quality wheat, and DDGS.

Vietnam produces corn but is also unable to supply all of its domestic feed needs. Corn is produced on marginal land, and the quality is below that of imported sources. Imports make up 65 percent of total consumption and 75 percent of feed use. Vietnam moved from being the 19th-largest corn importer in 2012 to the 5th largest in 2017. Imports are projected to continue to rise and reach 14.9 mmt by 2028.

Feed-Quality Wheat and DDGS Imports Fill the Gaps in Feed Demand

After corn and wheat prices peaked in 2008/09, wheat and DDGS imports began to expand in Southeast Asia. Although the Philippines and Thailand imported feed-quality wheat before 2008/09, imports began to expand in Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam’s after 2008/09. (Based on existing data, Malaysia’s imports of corn for its feed ratios are relatively insensitive to grain price changes.) Wheat imports, food and feed, are projected to continue to expand and reach 23.4 million tons, with about a quarter for feed at 9.1 million tons by 2028.

Government policies and wheat price decline expands Southeast Asia’s feed-grade wheat imports

Feed-Quality Wheat Imports

Indonesia imports wheat for poultry and livestock feed as well as for food use. When the Government restricted imports of corn for feed use in 2016, imports of feed-grade wheat surged, particularly from Ukraine.

Thailand produces minimal amounts of wheat, and it mostly imports wheat for feed and food use. In 2015, imports of feed-quality wheat, mostly from Ukraine, rose and continued to be high in 2016, though they decreased slightly in 2017. The Government allows wheat to be imported for food use but limits its feed-quality wheat imports through its 2017 domestic corn purchase requirement. As the domestic corn price remains high, Thailand’s feed-quality wheat imports also stay high.

DDGS Imports

Distillers’ dried grains with solubles (DDGS), a coproduct of ethanol production from corn, can be used as an energy and protein source in feed. The region’s imports of DDGS rise as countries implement policies that restrict corn or feed-grade wheat imports, as was the case in Indonesia and Thailand. DDGS is a feed substitute for both grains and soybean meal. The United States is the region’s leading supplier of DDGS. Thailand and Indonesia are the fourth- and fifth-largest markets for U.S. DDGS, while the rest of Southeast Asia imports very small amounts.

This article is drawn from:

- International Baseline Data. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- FAOSTAT database. (2019). United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home.

You may also like:

- O'Donoghue, E., Hansen, J. & Stallings, D. (2019). USDA Agricultural Projections to 2028. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. OCE-2019-1.