Commemorating 20 Years of U.S. Food Security Measurement

- by Alisha Coleman-Jensen

- 10/5/2015

Highlights

- Food security data have been collected every year since 1995, providing a benchmark for progress in the Nation’s fight against hunger.

- USDA’s food security measure has proven to be a valuable indicator, largely because it is based on validated statistical methods and rooted in extensive research.

- Annual food security data have fostered important research on the causes and consequences of food insecurity.

On September 9, 2015, ERS released the 2014 food security statistics—the 20th year that consistent, scientifically based, objective measures of food adequacy in the United States have been available for researchers, policymakers, and others interested in the nutritional well-being of the U.S. population. Food security—defined as consistent access to enough food for active, healthy living—was enjoyed by 86 percent of U.S. households in 2014. However, 14 percent of households were food insecure, meaning they had difficulty meeting basic food needs because they lacked money or other resources for food. Information on unmet food needs is of particular interest to USDA because the Department manages the 15 Federal food and nutrition assistance programs intended to provide children and low-income people access to food and a healthful diet.

The 20-year anniversary provides an opportunity to review the history of the food security measure—how the measure was developed, tested, and evaluated—and to reflect on its impact.

How Are Food Security and Food Insecurity Measured?

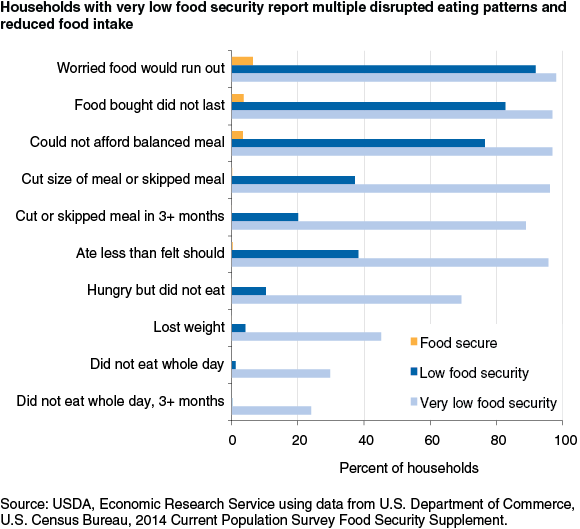

Since 1995, USDA has published information about the prevalence and severity of food insecurity in U.S. households using data collected in an annual food security survey, funded by ERS and conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. Food security is assessed by responses to a set of survey questions about conditions and behaviors that characterize households when they are having difficulty meeting their basic food needs (see box, “Assessing Household Food Security”). The questions cover a wide range of conditions—from worrying that food will run out, to not being able to afford balanced meals, to not eating for a whole day. Each question specifies a lack of money as the reason for the behavior or condition in question so that reduced food intake due to voluntary fasting or dieting does not affect the measure.

Each surveyed household is classified into one of three categories based on the number of food-insecure conditions it reports: food secure, low food security, and very low food security. Households with low food security primarily report conditions indicating anxiety about their food situation and reduced quality, variety, or desirability of their diets. Most report little or no reduction in food intake. Households with very low food security report those same conditions and in addition, report multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns, such as skipping meals and reduced food intake.

Of the 6.9 million households with very low food security in 2014, 96 percent reported that they had cut the size of meals or skipped meals because there was not enough money for food, 96 percent reported that they had eaten less than they felt they should because there was not enough money for food, and 69 percent reported that they had been hungry but did not eat because they could not afford enough food. These households reported other conditions as well.

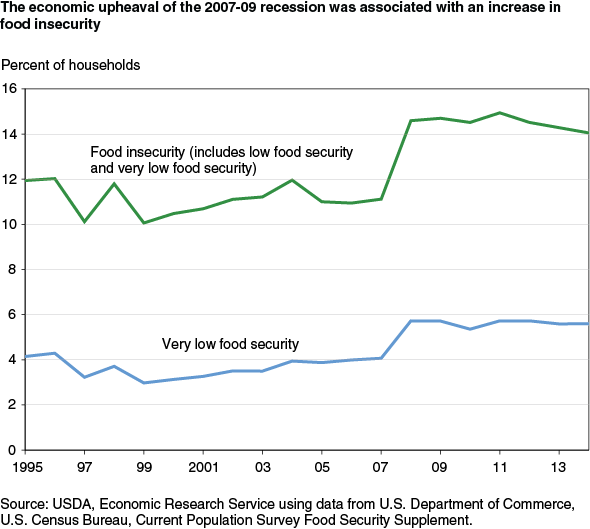

Food insecurity rates include households with low food security and very low food security. From 1995 to 2000, food insecurity declined overall; the data also showed seasonal variability due to the survey being conducted at different times during the year. During that time, the food security surveys alternated between April in odd-numbered years and August or September in even-numbered years. The measured prevalence of food insecurity was higher in the August/September collections. Since 2001, food security data has been collected in December each year, so the measure is no longer subject to seasonal variation from year to year. The 2007-09 recession and its aftermath was associated with a significant increase in food insecurity, as job losses and reduced incomes strained household resources. In 2007, 11.1 percent of U.S. households were food-insecure. Food insecurity increased to a high of 14.9 percent in 2011 and declined to 14.0 percent in 2014. Very low food security also increased with the recession from 4.1 percent in 2007 to 5.7 percent in 2008 and remained near that level in 2014 (5.6 percent).

Food insecurity has high costs for individuals, families, and society. Studies by medical researchers, nutritionists, and other scientists have found that among adults, food insecurity is associated with poor physical and mental health, underuse of prescription medications due to cost, reduced nutrient intake, and increased likelihood of experiencing chronic diseases, such as diabetes. Among children, food insecurity is associated with a variety of health and well-being issues, including anemia, stomach aches, frequent headaches and colds, anxiety, behavioral problems, poor psychosocial development, and lower academic achievement and attainment. Among adolescents, food insecurity is associated with higher rates of depressive disorder and suicidal symptoms.

Development and History of the Measure

The food security measure was developed using input from leading experts in academia, government, and the private sector. In 1994, the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) of USDA and the National Center for Health Statistics of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services convened the National Conference on Food Security Measurement and Research. Experts at that conference concluded that a scientific measure of food insecurity was feasible and worth pursuing.

After the conference, a working group produced a draft survey instrument, building on pioneering research at Cornell University’s Division of Nutritional Science and the Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project. As part of these projects, researchers talked with low-income parents struggling to put enough food on the table for their families. Many of the food security survey questions were developed directly from statements that people made about their food situations. As the food security measure was refined, technical experts at the Census Bureau assisted with finalizing and pretesting the survey questions.

The first food security survey was administered in April 1995. Federal researchers and private research firms analyzed the April survey responses to see whether the pattern of responses lined up with the underlying measurement theory. As had been theorized in early research, the data confirmed that food insecurity is a managed process, meaning that household members have some control over how they cope with food insecurity, how food insecurity is experienced, and who experiences it. In early stages of food insecurity, a household may experience anxiety about its food supply. To maintain adequate intake, households may reduce the quality or variety of foods consumed. As the situation deteriorates, adults reduce their food intake and try to shield their children. In the most severe situations, children, too, are subjected to reduced food intake.

The underlying concepts and statistical model for measuring food security status have undergone rigorous technical review. Over the past 20 years, only slight modifications have been made to the wording of the questions. In 2006, the Committee on National Statistics of the National Academies (CNSTAT) released the report Food Insecurity and Hunger in the United States: An Assessment of the Measure. This report was the culmination of a 2-year review of the measure conducted by an expert panel convened by the Committee on National Statistics at USDA’s request.

The panel affirmed the appropriateness of the general method currently used to measure food insecurity and recommended that USDA continue to regularly measure and monitor food insecurity in a household survey. The panel made some recommendations that have been incorporated into the measure, such as minor revisions to the wording and ordering of questions. The panel also recommended that USDA consider several potential technical enhancements to the statistical methods. These enhancements were explored, but the conclusion from the research was that little would be gained by using a more complex food security measure.

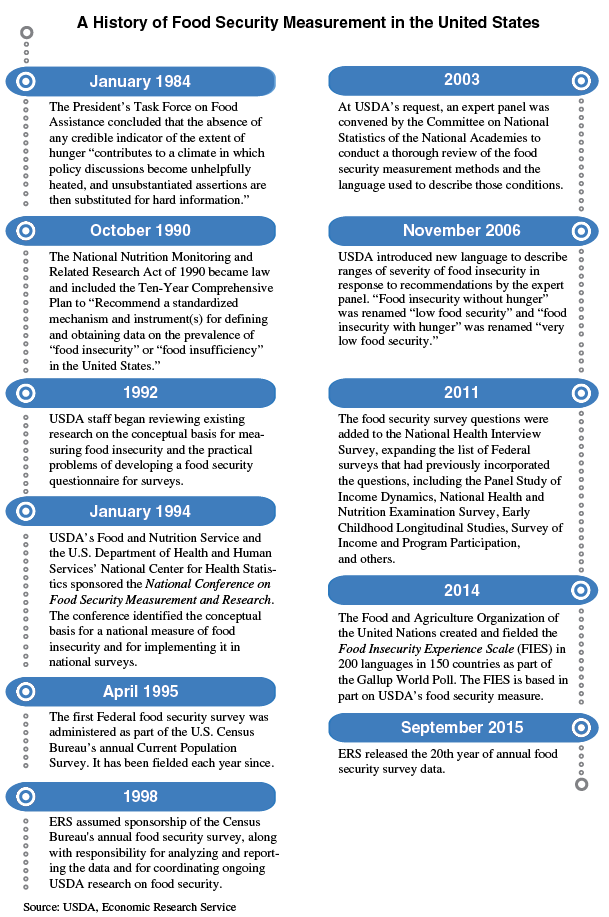

The CNSTAT panel also recommended that USDA make a clear and explicit distinction between food insecurity and hunger. Food insecurity—the condition assessed in the food security survey and represented in USDA food security reports—is a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food. Hunger is an individual-level physiological condition that may result from food insecurity. USDA agreed with this distinction and in 2006 introduced labels to describe food insecurity that did not include hunger. What was once referred to as “food insecurity with hunger” is now described as “very low food security.” This change was in name only; no changes were made to the actual measurement of the condition. The timeline “A History of Food Security Measurement in the United States,” summarizes the history of the food security measure.

Research Has Identified a Number of Risk Factors for Food Insecurity

Beginning with the analysis of the 1999 food security survey data, ERS has produced an annual statistical report on the prevalence and severity of food insecurity in U.S. households. Measuring and monitoring food security is just the first step—understanding the causes and risk factors can help identify ways to lessen food insecurity. The annual food security data have fostered research on the causes of food insecurity. The food security literature covers an array of academic disciplines including economics, nutrition, sociology, education, public health, medicine, child development, and social work. A key focus of this literature is to understand what factors may cause or be correlated with food insecurity.

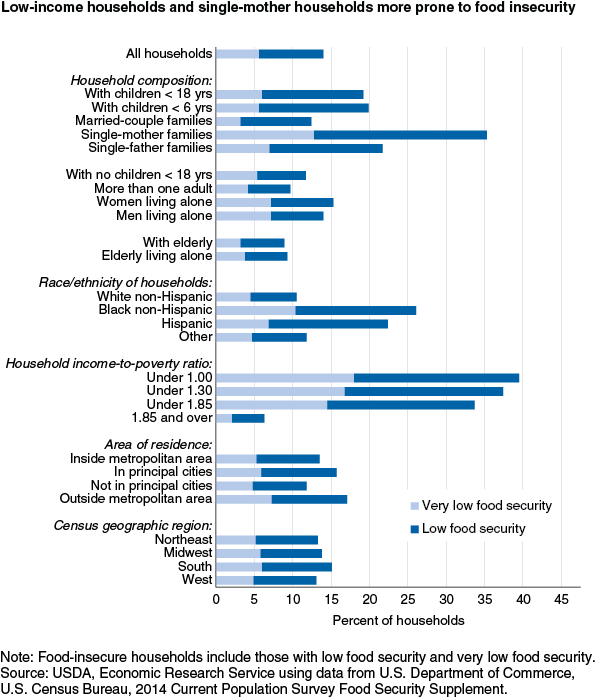

Recent ERS research has shown that households that include adults with disabilities are more likely to experience food insecurity, and food insecurity tends to be more severe among those with disabilities. Type of employment is also associated with food insecurity. Food insecurity rates were higher for households with members in nonstandard work arrangements—working multiple jobs, part-time work, or jobs in which the minimum number of hours worked varies from week to week—than for households with members in full-time jobs. As expected, those who are unemployed also face a higher incidence of food insecurity. Additional risk factors for food insecurity identified by government and academic researchers include poverty and low income, low education, being in a single-parent household with children, and experiencing negative life events such as violence, separation, or health problems.

ERS research on local food prices and food insecurity indicates that higher food prices are related to an increased likelihood of food insecurity, especially among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participants. National economic conditions, such as the unemployment rate, inflation, and the price of food relative to other goods, are associated with trends in the national prevalence of food insecurity. ERS has conducted a number of research studies to understand the influence of SNAP on food insecurity. These studies suggest that SNAP helps alleviate food insecurity. An FNS study also showed that participating in SNAP for 6 months was associated with lower percentages of households that were food insecure, that experienced very low food security, and in which children were food insecure. The size of the SNAP benefit appears to be particularly important, as larger benefits following the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act helped improve food security for SNAP-recipient households; the subsequent decline in the buying power of SNAP benefits due to inflation was associated with an erosion in food security for SNAP participants.

Is Food Insecurity a Temporary Condition or Chronic?

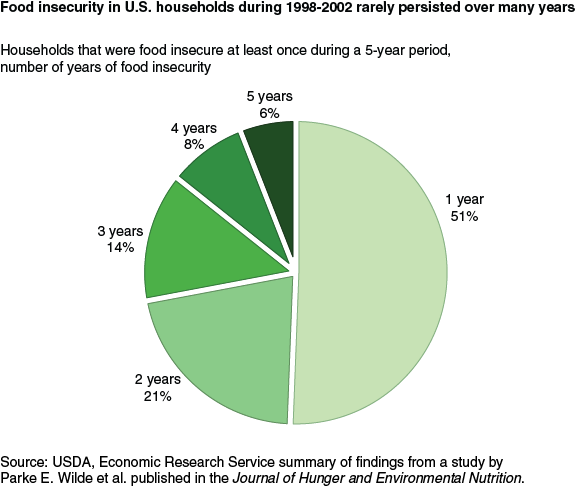

Knowing how often and how long households are food insecure is important for understanding the extent and character of food insecurity and for maximizing the effectiveness of programs aimed at alleviating it. Two studies commissioned by ERS found bouts of food insecurity to be generally of short duration. For example, one study found that half of households that were food insecure at some time during the 1998-2002 study period experienced the condition in just a single year, and only 6 percent were food insecure in all 5 years. However, the fact that households move in and out of food insecurity also means that a considerably larger number of households are exposed to food insecurity at some time over a period of several years than are food insecure in any single year.

Food Security Has Become a Key Measure for Tracking Well-Being

Food security has become an important outcome to measure well-being among American households and children. It is included as an indicator of children’s economic circumstances in America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, published by the Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. It is also being used to track progress toward strategic goals and objectives. A Federal interagency working group managed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services created Healthy People, a national health promotion and disease prevention initiative, to monitor progress over time in achieving 10-year national objectives for improving the health of all Americans. Healthy People 2020 includes two objectives focused on food insecurity. One is to “eliminate very low food security among children” and another is to “reduce household food insecurity and in doing so reduce hunger.”

While the Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement is the main survey vehicle for monitoring trends in U.S. food security, food security questions have been added to numerous other Federal surveys. These include the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), Early Childhood Longitudinal Studies Birth and Kindergarten cohorts (ECLS-B and -K), and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Additionally, food security questions have been included in numerous other non-Federal, private, and local surveys.

The food security measure has played a key role in evaluating the effectiveness of food and nutrition assistance programs and potential modifications to the programs. Food security is currently being used as the key outcome in evaluating five USDA-sponsored Demonstration Projects to End Childhood Hunger. These projects are testing alternative models for providing food assistance benefits and adjustments to benefit levels that promote the reduction or elimination of childhood hunger and food insecurity. FNS is also using food security to evaluate the success of its Summer Electronic Benefits Transfer for Children demonstration project designed to find innovative strategies for addressing hunger during the summer when low-income children do not have access to school meals.

Food Security Measure Going Global

The U.S. household food security measure has been applied around the world. Canada, Brazil, Mexico, and other countries have used the measure as a basis for creating and fielding their own food security surveys to assess food adequacy. The U.S. food security measure was one of several used by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations to create the Food Insecurity Experience Scale—translated in over 200 languages—to estimate food insecurity in 150 countries around the world in 2014. This new FAO scale will complement ERS’s international food security measure that focuses on the gap between countries’ food supplies and a consumption target.

USDA’s food security measurement and monitoring program continues to produce and sponsor relevant, high-quality research. Food insecurity has proven to be a valuable indicator, largely because it is based on validated statistical methods and is rooted in extensive research. The past 20 years of food security monitoring and research has created a solid foundation for moving forward. High-quality food security research will continue to inform policy options for combating food insecurity in the United States.

This article is drawn from:

- Nord, M. & Prell, M. (2007, June 1). Struggling To Feed the Family: What Does It Mean To Be Food Insecure?. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Coleman-Jensen, A., Rabbitt, M.P., Gregory, C.A. & Singh, A. (2015). Household Food Security in the United States in 2014. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-194.

- “Evolution of the USDA/DHHS Food Security Measurement Project”, by Steven Carlson. (2001). in Second Food Security Measurement and Research Conference, Volume 1: Proceedings, Margaret Andrews and Mark Prell (editors.

You may also like:

- Nord, M. (2013, October 24). Effects of Changes in SNAP Benefits on Food Security. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Gregory, C.A. & Coleman-Jensen, A. (2014, May 5). Higher Food Prices Mean Higher Rates of Food Insecurity for SNAP Participants . Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Coleman-Jensen, A. (2012, June 5). Food Insecurity More Common for Households With Nonstandard Work Arrangements. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Food Security in the U.S.. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Food Security in the United States - Interactive Chart: Food Security Trends. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- International Food Security. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Nord, M., Coleman-Jensen, A. & Gregory, C.A. (2014). Prevalence of U.S. Food Insecurity Is Related to Changes in Unemployment, Inflation, and the Price of Food. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-167.

- Nord, M. (2012). Assessing Potential Technical Enhancements to the U.S. Household Food Security Measures. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. TB-1936.