Hog Production

U.S. hog production can be broadly categorized into in four types of specialized enterprises:

- Farrow-to-finish operations raise hogs from birth to slaughter weight, about 270–285 pounds.

- Farrow-to-wean operations where females give birth to litters of pigs, which are typically nourished by the sow for about 3 weeks before weaning. Pigs weighing between 12–14 pounds are typically sold immediately after weaning.

- Nursery operations raise weaned animals to weights of about 40 pounds. These animals—feeder pigs—are typically sold to finishing operations.

- Finishing operations feed feeder pigs to slaughter weights, i.e., slaughter-ready animals, which are then sold to processors. The animals are fed rations comprised mainly of corn and high-protein (48-percent) soybean meal for about 4 months to achieve slaughter weights between 270–285 pounds.

Most hog producers use some type of confinement production system, with specialized, environmentally modified facilities. Confinement production allows year-round production that protects the animals from seasonal weather changes, disease exposure, and predators. Manure collected from hog operations is often spread as fertilizer on cropland, where permissible, in compliance with local, State, and Federal regulations.

At this time, the U.S. pork industry is moving away from gestation and farrowing crates as States enact laws that restrict both the time that sows are permitted to spend in movement confining crates while also requiring larger square footage allotments per animal. For example, such criteria are outlined in the newly enacted California law, Proposition 12. The law’s criteria for sow care specified in the law are a condition for the right to sell specific classes of pork in the State of California, regardless of where in the United States—or in what foreign country—the pork is produced.

The Biological Hog Cycle

The biological hog cycle is longer than that of broilers, but shorter than for cattle. The economic hog cycle refers to the peaks and valleys in hog inventories over time, while the biological hog cycle refers to the biological time lags involved in hog production. A sow can produce an average of slightly more than two litters per year, often consisting of more than eleven pigs per litter.

Figure 1. The Biological Hog Cycle

Source: Dr. Paul Pitcher and Sandra Springer, University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, 1997.

A gilt (a female hog that has not farrowed, i.e., given birth) typically reaches sufficient maturity to be bred at about 29 weeks of age. The reproduction process begins with the mating of a gilt capable of conception via “natural service” with a boar (male hog) or by artificially inseminating the gilt with semen from a boar bearing desired characteristics.

Over time, artificial insemination has become the dominant means of impregnating female swine in the U.S. hog industry. The USDA, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service report, Baseline Reference of Swine Health and Management in the United States, indicates that breeding in the US swine industry is almost entirely dependent on artificial insemination, with less than 3 percent of sows and gilts serviced via pen mating.

Once the gilt has been bred successfully, she will farrow a litter of about 11 pigs (usually more, depending on weather, prevalence of disease, etc.) in approximately 3 months, 3 weeks, and 3 days, or 113 days (i.e. 16 weeks). A sow (an adult female hog that has farrowed at least once) can be re-bred when the sow’s estrus cycle is re-established, which is typically about one week after weaning.

In a farrow-to-finish operation, 22–26 weeks (or about 6 months, starting at birth) are required to grow a pig to slaughter weight. Sows nurse their litters for an average of 3 weeks before they are weaned, or separated from the sow, and are able to digest a solid ration. This is the farrow-to-wean phase of hog production. Weighing about 12–14 pounds, the weaned pigs are either moved on to the next phase of production (known as the nursery phase, or the wean-to-feeder pig) or they are sold directly to operations that combine the nursery and finishing operations. Pigs in the wean-to-feeder pig phase are fed rations varying in protein content until they reach an average weight of about 40 pounds. From the feeder pig stage, the animals enter a finishing stage and remain there (typically 4 months) until they reach a desired slaughter weight of between 270-285 pounds. Operations of this type are known as the feeder pig-to-finish phase, or simply the finishing phase.

Industry Structure

The U.S. hog industry has undergone significant structural changes in the last 40 years, the most important of which has been the rapid shift to fewer and larger operations. Since 1990, the number of farms with hogs has declined by more than 70 percent as individual enterprises have grown larger. U.S. hog operations tend to be heavily concentrated in the Midwest—particularly Iowa and southern Minnesota—and in eastern North Carolina, but hog operations are also found in Oklahoma and in Texas.

Large operations that specialize in a single phase of production have largely replaced farrow-to-finish operations that predominated in the mid-1970s and performed all production phases. The use of production contracts has increased. Structural changes have coincided with efficiency gains and lower production costs. Most of the productivity gains are attributable to increases in the scale of production and technological innovation (figure 2).

Figure 2. U.S. commercial pork production versus breeding beginning stocks, 1980–2022

Download chart data in Excel format

Policy

Federal programs for hogs are not comparable to those for crops. Federal legislation provides assistance to farmers including emergency feed, meat purchasing, disease eradication, drought assistance, as well as conservation and environmental programs.

- When producers are undergoing financial stress, USDA's Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) may purchase meats for domestic feeding programs to help strengthen prices through Commodity Purchase Programs.

- USDA, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) oversees USDA's disease eradication programs such as those for pseudorabies, a viral swine disease, and African Swine Fever.

- USDA's Farm Service Agency (FSA) provides assistance to producers for natural disaster losses resulting from drought, floods, fire, freezes, tornadoes, pest infestations, or other calamities.

- Another program for livestock operations is the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), which provides technical, educational, and financial assistance to eligible farmers and ranchers to address soil, water, and related natural resource concerns on their lands in an environmentally beneficial and cost-effective manner.

- The USDA, Risk Management Agency offers two insurance programs to pork producers. The Livestock Risk Protection Insurance Plan for Swine (LRP-Swine) is designed to insure producers against declining market prices. The Livestock Gross Margin Insurance Plan for Swine (LGM-Swine) provides protection against the loss of gross margin. Both insurance programs offer maximum flexibility in terms of length and level of coverage.

The hog industry trending toward fewer and larger hog farming enterprises has brought environmental issues to the forefront of public policy. As animal density increases, so do concerns regarding facilities’ air and water quality, occupational health, and waste management. In areas where hog production is most concentrated, human population density can increase as well. These trends indicate growing conflicts between nearby residents and hog producers concerning odor, water contamination, and other environmental problems associated with concentrated production.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provides information about national environmental requirements related to agricultural animal production, including fish and other aquatic animals. EPA disseminates and enforces livestock waste regulations, including those on Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations. Many States and locales regulate the size of confined animal operations, as well as practices pertaining to odor, waste disposal, and water quality as they relate to agriculture.

Agricultural policy extends to trade, a primary topic area in the World Trade Organization (WTO). WTO member countries have negotiated rules pertaining to sanitary and phytosanitary practices, tariffs, quotas, and other policies to minimize the negative impacts to the trade of animal products. The WTO maintains a complex conflict-reduction procedure that can culminate in member-countries contesting trade practices of other member countries in a formal dispute settlement process, with the resulting WTO administrative opinions binding on the losing country.

Trade

The United States is a Major Pork Exporting Country

The United States became a net exporter of pork in 1995. Productivity gains allowed the U.S. pork industry to export a higher share of world exported pork, reaching 26 percent in 2020, compared with 2 percent in 1990. The United States’ share of the world’s exported pork volume reached a peak of 35 percent in 2008 and has averaged 29 percent in the last decade (figure 3).

Since 2000, the United States has been among the world’s top five annual pork exporters, annually. From 2010 through 2022, U.S. exports of fresh and frozen pork cuts averaged more than 5.6 billion pounds (carcass weight-equivalent) with a peak of 7.3 billion pounds shipped in 2020 (figure 3). In the last 5 years, the United States ranked second in the top five pork exporting countries, after the European Union (EU), followed from a distance by Canada and Brazil (figure 4).

Figure 3. U.S. pork export and world export shares, 1990-2022

Download chart data in Excel format

Again, becoming a net pork exporter is a consequence of technical innovation, early adoption of new technologies, and ongoing structural changes in the pork industry. Since the mid-1980s, U.S hog production has shifted away from large numbers of small, independently owned hog operations toward fewer, larger operations that rely on contracting and vertical coordination as management tools. Such structural change reduces producer risk and optimizes a year-round processing capacity, enabling the industry to accommodate cyclically large fall and winter slaughters.

Figure 4. Country shares of global pork exports, by volume, 2022

Download chart data in Excel format

Important U.S. Pork Export Destinations in Terms of Volume

Together Mexico and Japan have accounted for about half of U.S. pork exports in the last 10 years. The only exception was in 2020, when China was the primary buyer of U.S. pork due to Chinese hog losses that were attributable to African Swine Fever. Although China remains an important potential buyer of U.S. pork, if only due to its size, China’s demand for U.S. pork appears to be primarily driven mostly by disease outbreaks. Moreover imported U.S. pork is still subject to heavy tariff barriers that make it less competitive with pork from other major exporting countries. China’s tariffs place an important damper on U.S. pork’s market potential in China.

On the other hand, important export markets include those with which the United States has executed free trade agreements. In addition to Mexico and Canada (via the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), of 2020), the United States has executed agreements with the Dominican Republic (via the Central American-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (2006–09)), Columbia (via the U.S.-Columbia Trade Promotion Agreement (2012)), and with South Korea (via the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement (renegotiated in 2018)), all of which have become important U.S. pork buyers.

Figure 5. Country shares of U.S. pork exports, 2022

Download chart data in Excel format

The United States has Accounted for a Declining Share of World Pork Imports

The United States has accounted for a diminishing share of world pork imports, as U.S. import volumes have fallen, and world trade has expanded. Over the last decade, the United States accounted for an average share of about 6 percent of global pork imports, with the lowest volume attained in 2020, when the U.S. accounted for less than 4 percent of global import volume.

Most U.S. pork imports originate from Canada and the EU. In the last decade, about 93 percent of the U.S. pork imports originated from Canada and the EU, with almost 70 percent coming from Canada, while EU member countries accounted for about 25 percent. Additional 6 percent of the U.S. pork imports have originated from Mexico, Brazil, and Chile.

Going forward, such factors including trade agreements, low transportation costs, and cross-border proximity are likely to further consolidate integration across the North American pork and foodservice industries. Brazil is likely to increase its share of the U.S. pork import market as well, given its relatively low-cost production and processing structures.

The United States is a Net Importer of Live Hogs

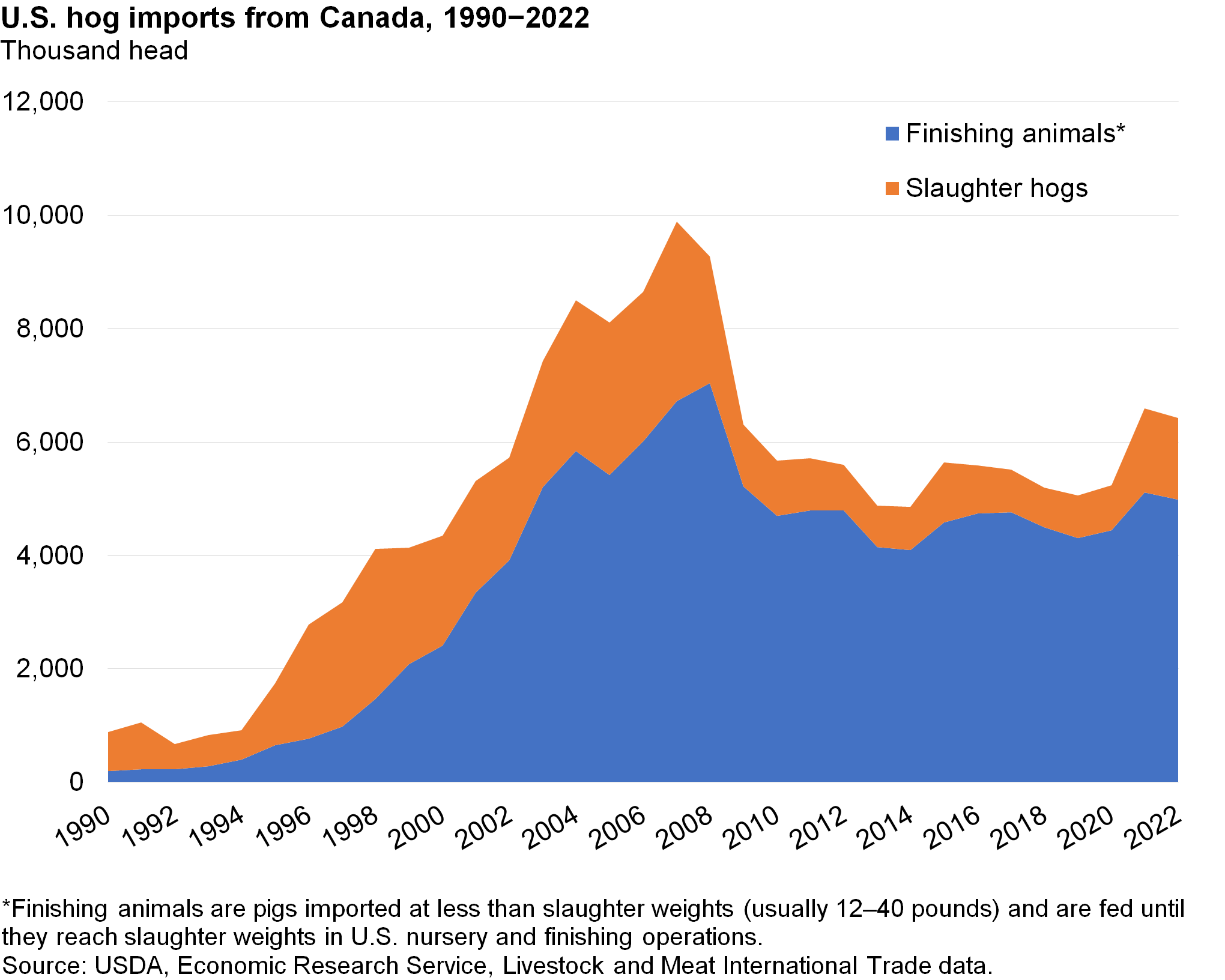

A significant number of live hogs (i.e., hogs for immediate slaughter and finishing animals) are imported from Canada. Most of the finishing animals (i.e., weaned pigs weighing less than 15 pounds and feeder pigs weighing about 40 pounds) are sold under contract to finishing operations in Corn Belt States—primarily Iowa and southern Minnesota (figure 6).

Figure 6. U.S. Hogs imports from Canada,1990−2022

Download chart data in Excel format

Before the early 2000’s, several factors encouraged Canada’s producers to export finishing animals to the United States. The most important factor was the Canadian Government’s drive to curb its expenditures in the 1990s, including the abolition of the Crow Rate grain transport subsidy in 1995, which was a rail transportation subsidy for farmers in the Canadian Prairies and manufactures in central Canada. Eliminating this subsidy provided an incentive for producers in the Canada’s western Provinces to use grain for livestock production in West Canada. Also, lower Canadian subsidies resulted in reduced U.S. countervailing duties on imported Canadian hogs. These policy changes created powerful incentives for the Canadian pork industry to expand, as did a strong U.S. dollar exchange rate in the 1990’s.

In the United States, several combined factors have generated significant U.S. demand for Canada’s finishing hogs. These factors include available slaughter capacity, abundant feed supplies, and environmental regulation favoring the construction of hog-finishing facilities in Corn Belt States.

U.S. imports of Canadian hogs peaked at about 10 million head in 2007. Among the factors that contributed to the reduction in live hog imports included exchange rate volatility; some increase in finishing and processing capacity in Canada; 2002 Country of Origin Labeling legislation in the United States for fresh pork products; and 2004 antidumping and countervailing duty actions by the U.S. National Pork Producers’ Council against imported live Canadian hogs. At its peak in 2007, hogs imported from Canada accounted for about 9 percent of U.S. federally inspected (FI) hog slaughter. Since 2007, live imports have not accounted for more than 5 percent of FI slaughter. In 2022, the United States imported about 6.5 million head of Canadian hogs, about 5 percent of U.S. federally inspected hog slaughter. About 77 percent of the sum imported from Canada in 2022 was finishing animals (i.e., animals weighing less than 7 kilograms) and feeder pigs (i.e., animals weighing 7–50 kilograms).

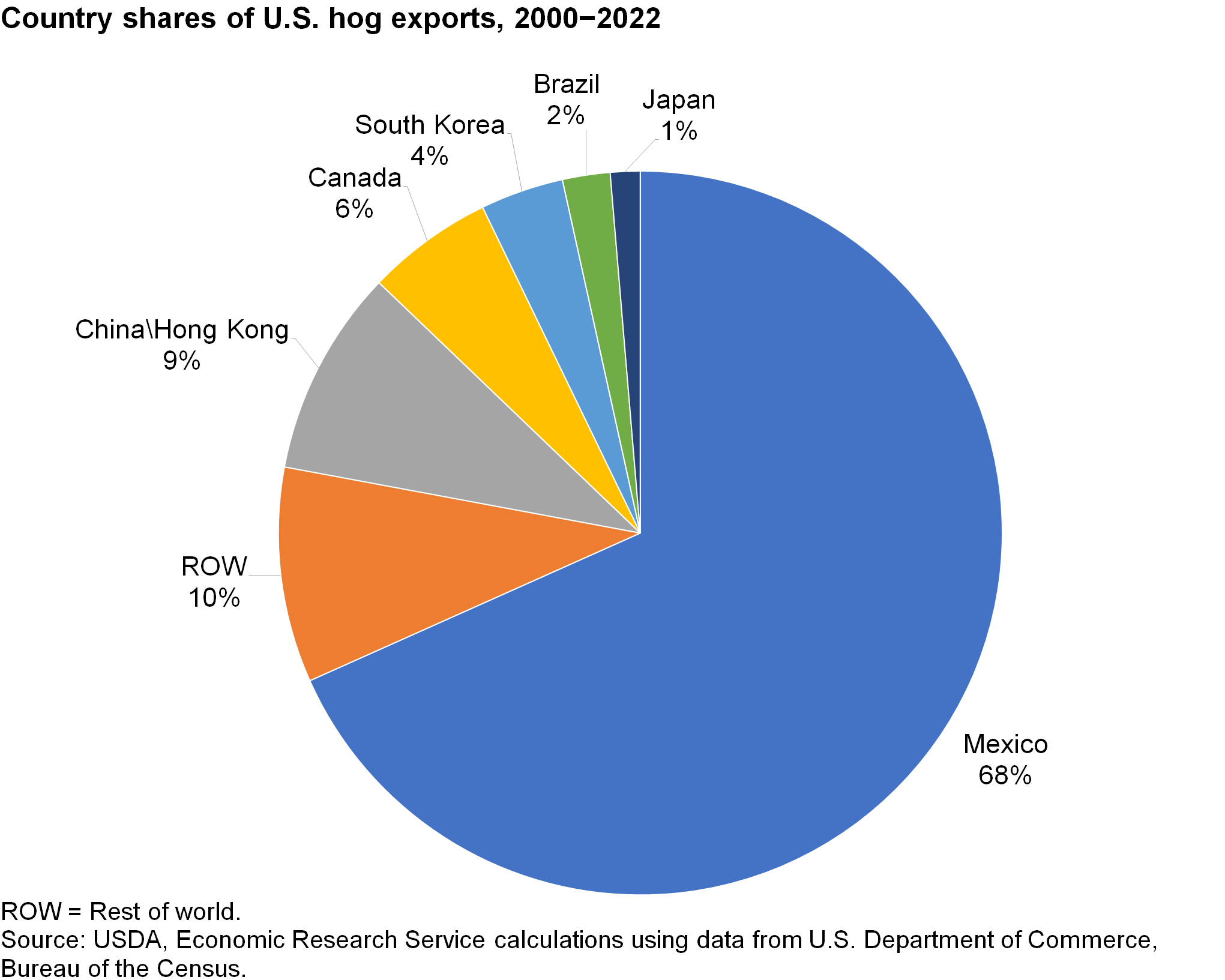

The United States exports a small number of hogs, mostly breeding animals. Historically, most of these animals (80 percent) were shipped to Mexico. However, in the last few years, the number of shipments to China and Canada doubled from the volumes seen in early 2000s (figure 7).

Figure 7. Country shares of U.S. hog exports, 2000−2022

Download chart data in Excel format