U.S. Exports of Animal Agricultural Commodities Face Many Similar Threats and Opportunities

- by Danielle J. Ufer

- 6/26/2024

Highlights

- U.S. animal product exports face both headwinds and tailwinds in a number of ways, including livestock and poultry diseases that often lead to trade restrictions.

- Tariff and nontariff trade barriers can form obstacles to the export of U.S. animal commodities.

- Trade agreements can facilitate competition by opening access to markets for U.S. animal product exports, but they also can benefit U.S. competitors.

- Emerging economies, such as those of Southeast Asia, represent new opportunities for increased U.S. animal product exports.

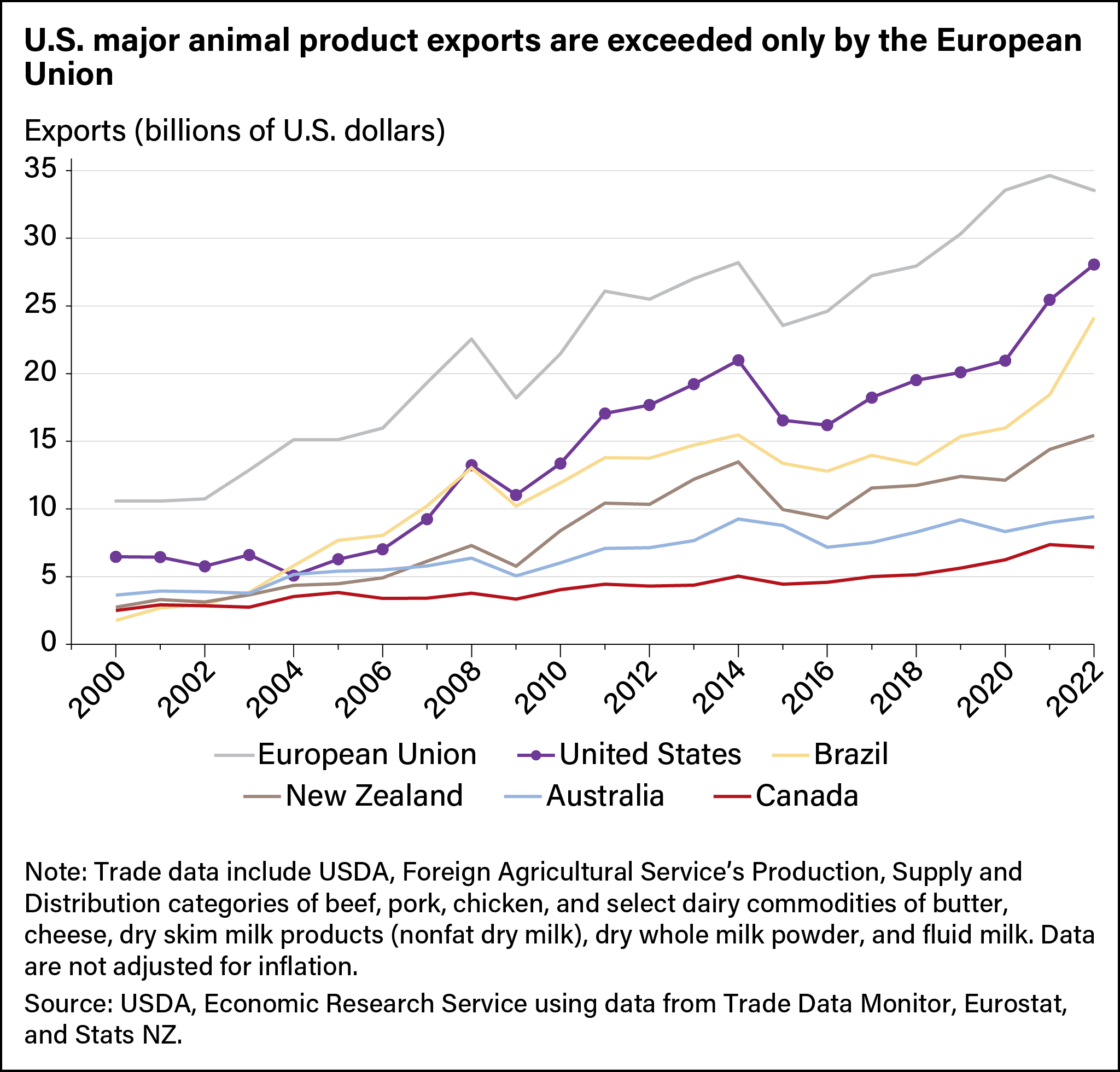

The United States is a leading global exporter of beef, pork, and chicken, as well as several dairy products. While U.S. animal product exports have grown in recent years, those of global competitors also have strengthened. Like the United States, many major players in animal product export markets have strong export portfolios across multiple animal commodities. However, they all must contend with trade barriers, disruptions, tensions, and provisions in trade agreements, which can represent opportunities as well as threats to competitiveness and overall trade performance.

U.S. animal product exports exceeded $37 billion in 2023, representing about one-fifth of the value of total U.S. agricultural exports. The United States holds strong market positions in many of its most common destinations for animal agricultural commodities, including Japan, South Korea, China, and the North American markets of Mexico and Canada. In 2022, U.S. exports accounted for more than two-thirds of Canada’s total imports of beef, pork, chicken, and many dairy commodities, and more than 83 percent of those same categories for Mexico. Export competitors for U.S. animal products include the European Union (EU), Brazil, New Zealand, Australia, and Canada.

Livestock Diseases Pose Threats, Opportunities for U.S. Animal Product Trade

Issues related to livestock or poultry disease have presented some of the biggest challenges for U.S. animal product trade in recent years. Diseases that can be passed from animals to humans (known as zoonotic diseases) are a natural cause for trade restrictions given the public health risks. Even animal diseases that are not passed to humans can motivate countries to put trade restrictions in place to protect their agricultural sectors and food supplies.

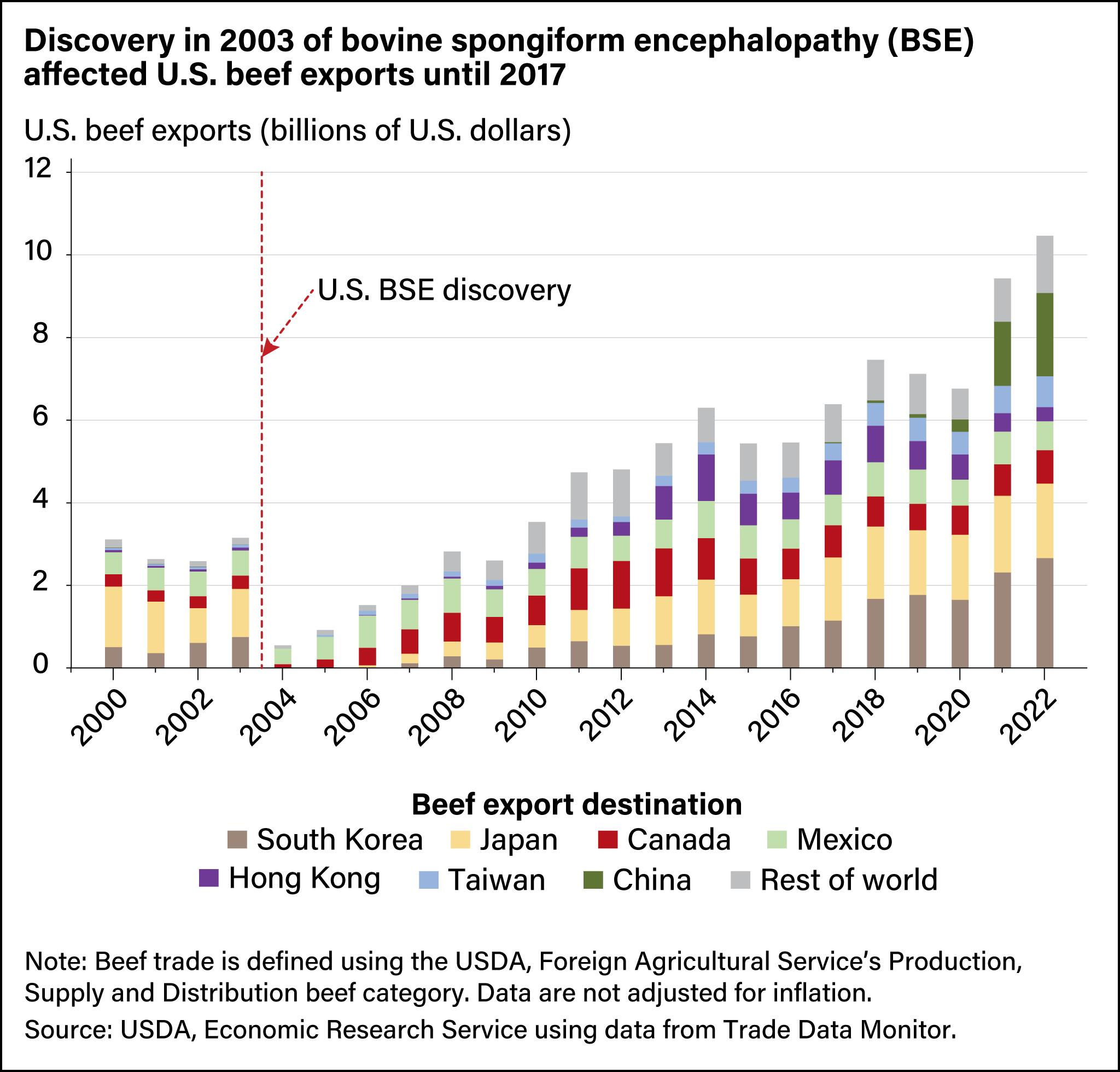

In the past three decades, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as mad cow disease, was an example of a disease that influenced trade. When the disease was discovered in the United States in 2003, foreign markets closed their borders to U.S. beef. Exports of U.S. beef subsequently dropped from $3.2 billion in 2003 to $551 million in 2004.

Such restrictions can last well beyond the actual threat of the disease. Even after the World Organization for Animal Health declared the United States to be of negligible risk for BSE, U.S. beef trade partners were slow to remove restrictions, and U.S. beef exports recovered gradually. China restored market access only as recently as 2017.

Outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in the past decade also have resulted in trade restrictions on a variety of animal products, including chicken broiler meat. While importing countries claimed the protection of public health to justify BSE-related restrictions, HPAI-based restrictions were primarily instituted with the stated goal of protecting domestic poultry industries. More recently, countries have limited their HPAI-based import restrictions to products originating in affected geographic regions rather than from an entire country. That trend has helped reduce the effect of disease threats to exports and market access. Still, the impact of any severe outbreak can reduce total exports.

Recently, USDA and other Federal agencies have begun to investigate the presence of HPAI in some U.S. dairy cattle. In April, USDA, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) announced the start of mandatory testing of dairy cows to take place before they are moved between States. The recent discovery of HPAI in dairy cattle has prompted some trade actions, including limitations on U.S. beef exports to Colombia from States with affected dairy herds and HPAI testing requirements for live U.S. dairy cattle imported into Canada.

On the other hand, disease outbreaks in a trading partner’s domestic industry or when an export competitor faces disease-related restrictions open a window for U.S. exports. Recent events surrounding African swine fever (ASF), a disease with no known human health risk but that is often fatal to swine, are one such example. In 2018, China’s domestic pork industry was devastated by an ASF outbreak, heavily contributing to a nearly sixfold increase in China’s pork imports, from $2 billion to nearly $12 billion in 2 years. U.S. pork exports to China grew at an even faster rate, more than tripling from $129 million in 2018 to $507 million in 2019 and then tripling again in 2020. ASF also affected major pork exporters such as Germany, where the discovery of the disease in wild and domesticated hogs in 2020 cost that country its nearly 15 percent share of China’s pork import market. Germany’s loss created export opportunity for competitors, including the United States.

Heightened Overseas Standards for Animal Husbandry Also Threaten U.S. Competitiveness

Another challenge for exporters is when importing countries restrict products that come from livestock raised using specific practices. Among the most common such restrictions on U.S. exports are those on products from animals raised with growth-promoting substances such as ractopamine and other beta-adrenergic agonists. U.S. beef and pork producers have used growth-promoting substances extensively in recent decades. Major markets for beef and pork, such as China or the EU, prohibit imports of meat produced using such substances despite statements from the World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization that ractopamine is safe under certain thresholds.

Measures on production standards such as animal welfare requirements or environmental impacts also threaten exports and competitiveness. For example, the EU included animal welfare standards in its 2022 and 2023 trade agreements with New Zealand and Chile, respectively. In 2023, the EU also started prohibiting the sale within the EU of products from cattle raised on land that was recently deforested or linked to forest degradation.

Trade Agreements Foster Market Opportunities for United States as Well as Its Competitors

The political relations and policies defining trade relationships also can present threat and opportunity for U.S. animal product exports. Global markets generally are structured such that tariffs, tariff-rate quotas, and safeguard mechanisms often bind and restrict trade. Trade negotiations and free trade agreements often relax these policies as well as nontariff barriers. Trade agreements have become essential in creating or preserving market access. Moreover, they help establish long-term expectations for trade prospects with specific trading partners or coalitions.

The United States is party to several trade agreements enacted over the past three decades, including many with the world’s largest animal agricultural commodity partners. The United States had 20 free trade agreements in place in 2022. U.S. animal product exports to Canada and Mexico have been supported by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and, more recently, the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Meanwhile, bilateral, or individual, trade agreements with Japan, South Korea, and China each have expanded or maintained market access for U.S. animal commodities. These agreements often grant preferential or reduced tariffs on many U.S. goods and can create opportunities for future negotiation or reduction of nontariff trade barriers. For example, provisions in the U.S. free trade agreement with South Korea (known as KORUS) removed tariffs on more than 90 percent of U.S. pork by 2016. Provisions of the Phase One Agreement between the United States and China granted China’s recognition of USDA, Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS) standards, allowing all FSIS-approved processors to export to China without needing to receive individual-level approval. The Phase One Agreement also included provisions for negotiation and discussion of a protocol to govern the importation of live breeding cattle from the United States.

U.S. competitors also engage in trade agreements, complicating the global network of trade advantages for the United States. For example, the South Korea-EU Free Trade Agreement (KOREU), implemented in 2011, offered tariff reduction benefits similar to those in KORUS. The terms of KOREU effectively neutralized much of the United States’ preferential access advantage over the EU, the top competitor in South Korea’s imported pork market.

Foreign relations and tensions over issues beyond agricultural commodities also can impact market access. Disputes over trade in nonagricultural goods can result in retaliatory actions that affect U.S. agricultural interests. In 2018, China imposed tariffs on U.S. pork and other agricultural products in response to U.S. Section 232 and Section 301 investigations and resulting tariffs on China’s manufactured goods and other products. Several other major trade partners levied their own retaliatory tariffs on U.S. agricultural goods in response to similar investigations and trade restrictions. USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) researchers estimated that from mid-2018 through 2019, U.S. pork export losses from retaliatory tariffs totaled nearly $646 million on an annualized basis.

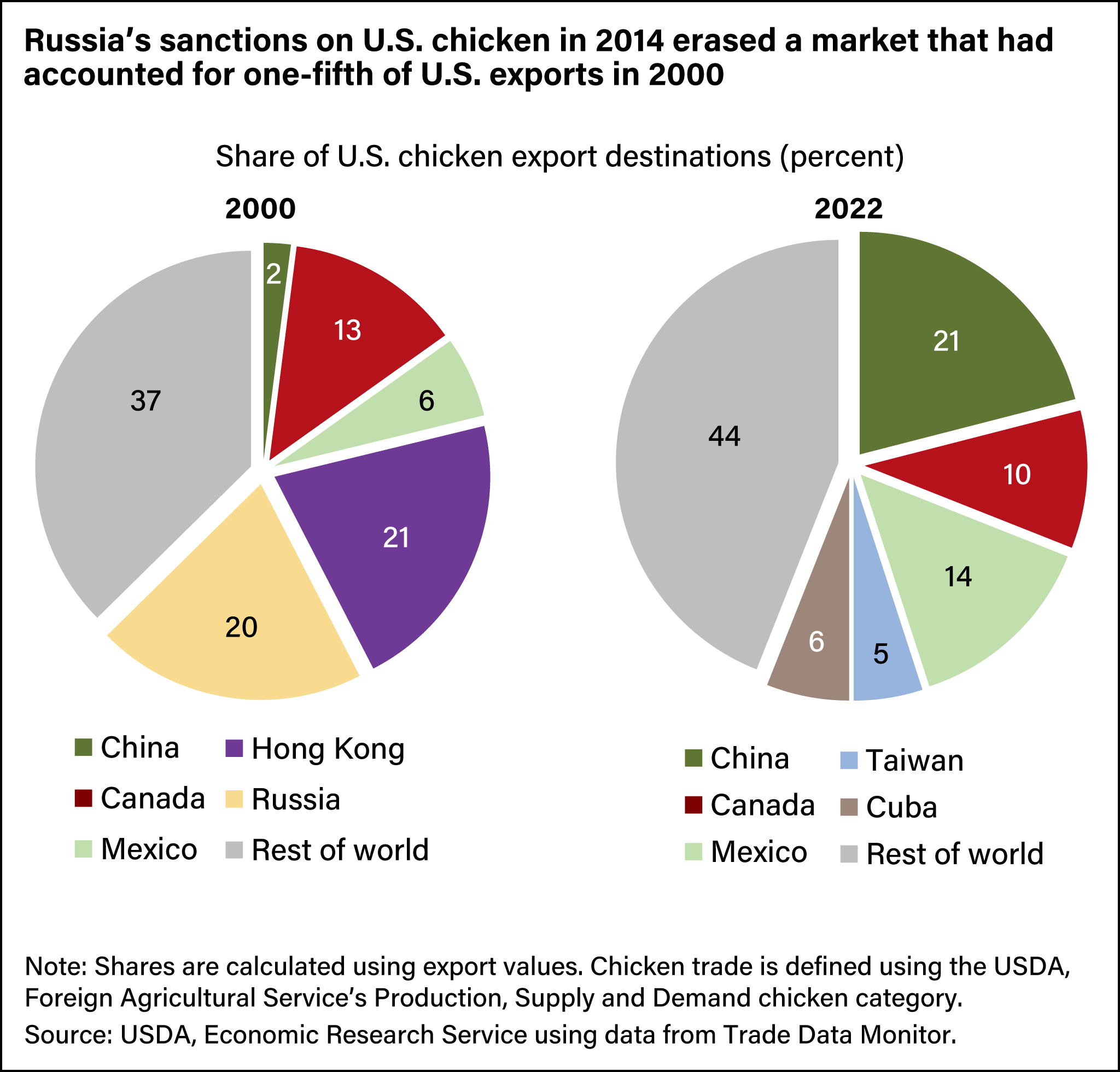

Tensions over events unrelated to trade also can affect exports. The United States and Russia imposed sanctions and countersanctions on agricultural imports from one another after Russia’s 2014 invasion and annexation of Crimea. Because of these actions, the United States lost all access to Russia’s poultry market. Russia had been a major destination for U.S. chicken, with exports worth $306 million in 2013, the year before the sanctions.

Opportunities for U.S. exports may arise amid tensions between U.S. trade partners and competitors. Recent political tensions between Australia and China, for example, resulted in restricted market access for Australia’s beef exports, compounding Australian beef export challenges from severe drought. Though it is not clear to what extent Australia and China’s political tensions may have directly benefited U.S. beef exports, they did create a potential advantage for the U.S. industry, where processors retained Chinese approval and, consequently, market access.

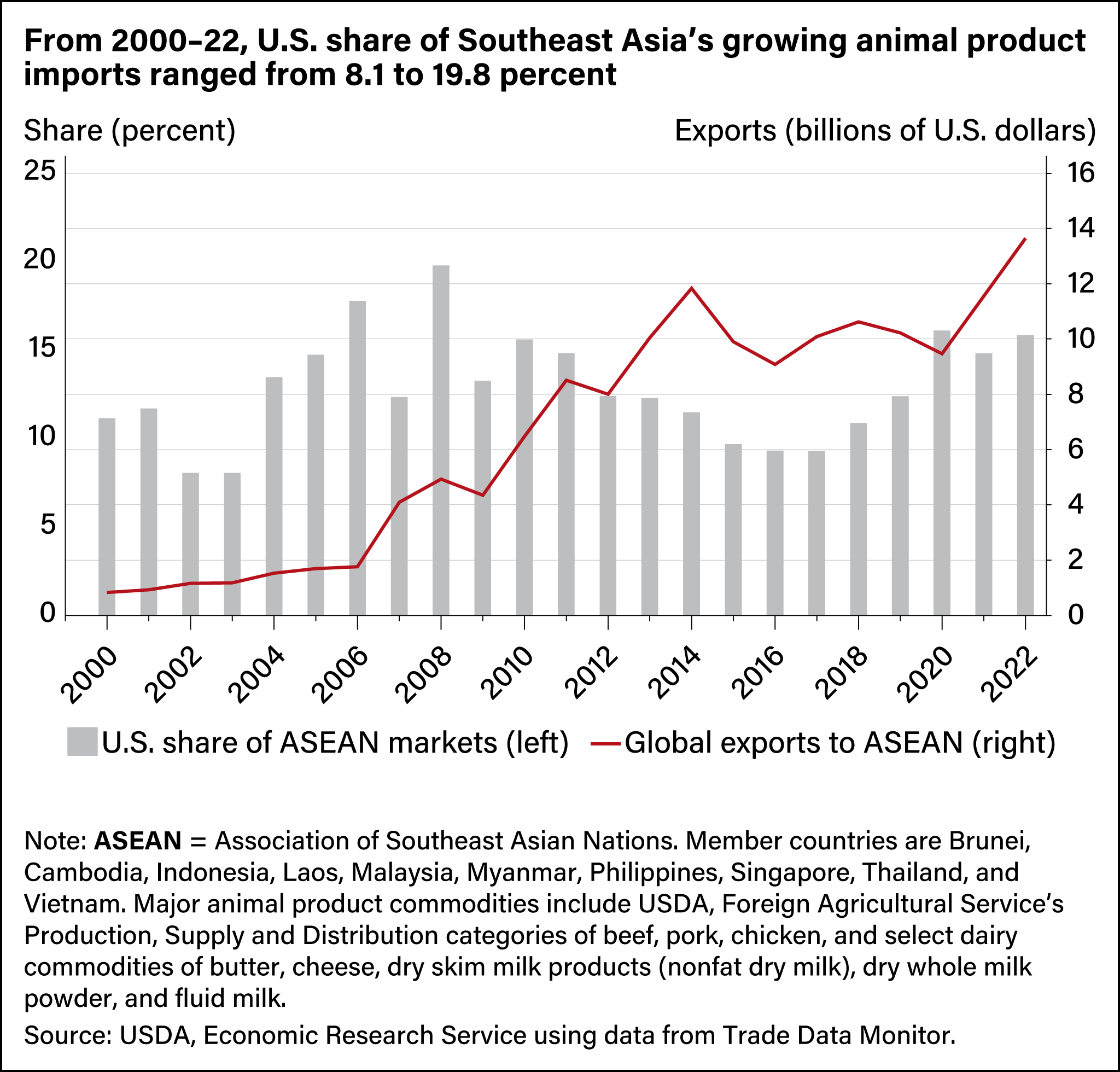

Emerging Markets Offer Opportunity for U.S. Export Growth

Notable opportunities for U.S. animal product growth exist in emerging markets. A prime example is in Southeast Asia, where imports of animal commodities have grown since 2000. Typical economic drivers such as income growth continue to boost demand for imported as well as domestic animal products. Other factors may create demand for specific products. For example, African swine fever reduced Vietnam’s pork supply, leading to an increase in pork imports for that country. Export potential already is evident in some commodities, such as U.S. dry skim milk product exports (nonfat dry milk), for which several Southeast Asian countries are among the top global importers. In 2022, four of the five largest Southeast Asian dry skim milk product export markets bought more than a third of their imports from the United States, with over half of imports to the Philippines originating in the United States. ERS researchers found similar prospects for other animal product exports in emerging markets as their economies continue to develop.

This article is drawn from:

- Ufer, D.J., Padilla, S. & Link, N. (2023). U.S. Trade Performance and Position in Global Meat, Poultry, and Dairy Exports. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-312.

- Knight, R., Taylor, H., Hahn, W., Valcu-Lisman, A., Terán, A., Haley, M. & Grossen, G. (2024). Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry Outlook: May 2024. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. LDP-M-359.

You may also like:

- Williams, B., Dohlman, E. & Miller, M. (2024, February 15). U.S. Pork Exports Projected to Surpass Chicken in the Next Decade. Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Morgan, S., Arita, S., Beckman, J., Ahsan, S., Russell, D., Jarrell, P. & Kenner, B. (2022). The Economic Impacts of Retaliatory Tariffs on U.S. Agriculture. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-304.

- Padilla, S., Ufer, D.J., Morgan, S. & Link, N. (2023). U.S. Export Competitiveness in Select Crop Markets. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-313.

- Davis, C.G. & Cessna, J. (2020). Prospects for Growth in U.S. Dairy Exports to Southeast Asia. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-278.