Free Trade Agreements Mean Export Growth for Some Countries, Reallocation of Trade for Others

- by Ethan Sabala

- 2/16/2023

Free trade agreements (FTAs) create additional trade between member countries by lowering import barriers and opening markets for producers. More than half of U.S. agricultural imports arrive from FTA partners, especially low- and middle-income countries. However, free trade agreements do not always lead to an increase in the total level of exports for all sectors of the economy. Even when exports to an FTA partner increase, exports might not increase overall. For instance, a country might export more of a commodity to a partner, but it might do so by reallocating, or diverting, trade away from other countries where tariffs remain in place. Additionally, with trade liberalized across many commodities, domestic resources are shifted towards the production of those most efficiently produced, which can result in resources being shifted away from that commodity. In that case, total exports might not increase even with rising exports to an FTA partner.

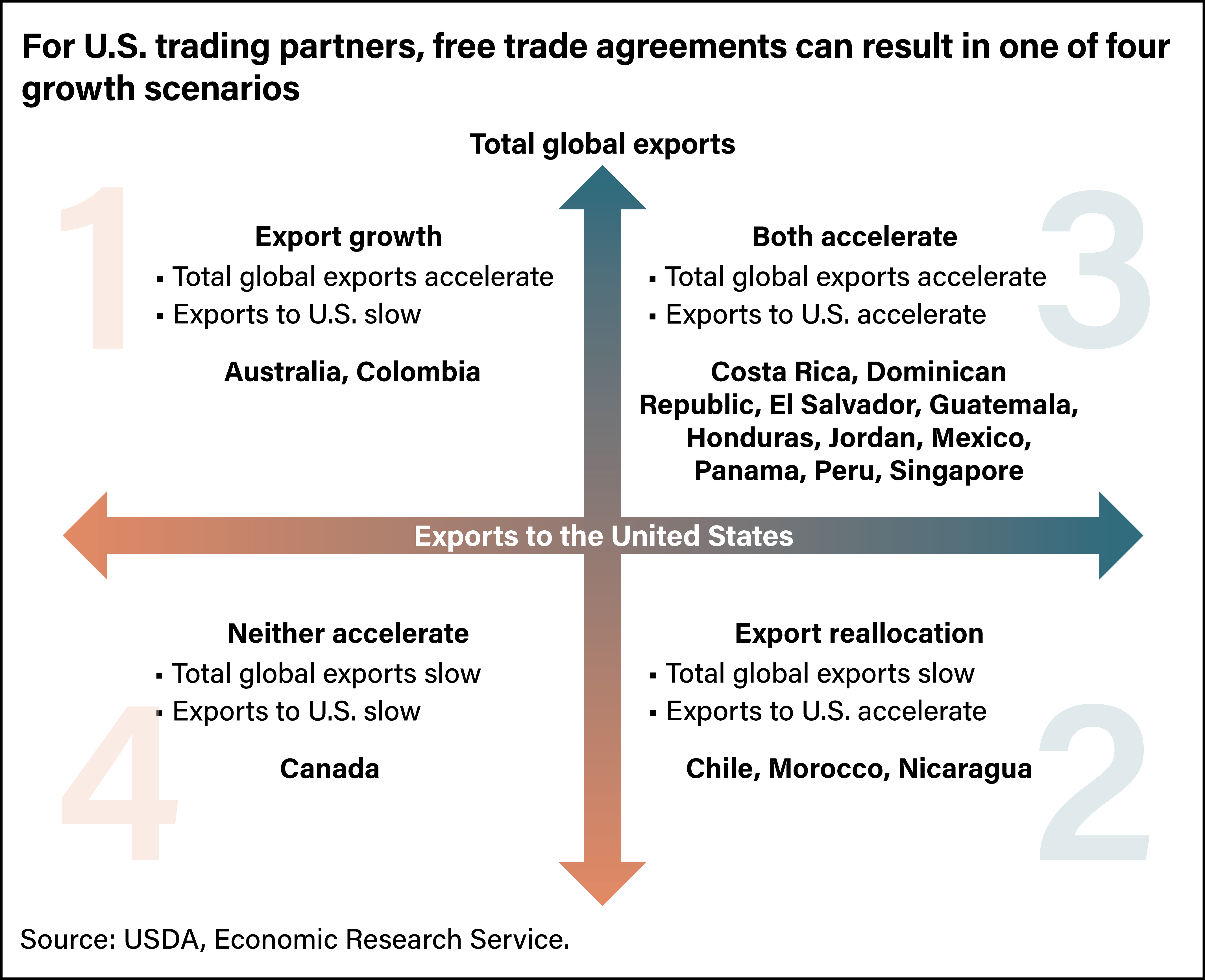

To determine the effect of FTAs on developing countries, researchers at USDA’s Economic Research Service recently examined the United States’ portfolio of free trade agreements. For each trading partner, they looked at changes in agricultural exports to the United States and total agricultural exports during the first 5 years of the FTA and found the direction and magnitude of trade changes varied by country. They grouped the changes into four categories: export growth, export reallocation, growth and reallocation together, and neither export growth nor reallocation. Acceleration or slowing of exports can be positive or negative depending on the average annual change in exports before the FTA. For instance, if a country’s exports decreased by an average of 10 percent during the 5 years before the FTA’s implementation and then decreased by a smaller average of 5 percent in the 5 years after the FTA, that change still would be considered acceleration.

Export growth (Quadrant 1). In the first 5 years of some free trade agreements, the trading partner’s total agricultural exports accelerated even though agricultural exports to the United States slowed. This categorization is referred to as export growth and is represented in quadrant 1 in the graphic above. Researchers found that in Australia and Colombia, total exports accelerated, but exports to the United States slowed or stagnated following their respective FTAs with the United States. This suggests that in the 5 years after the FTAs went into effect, Australia and Colombia experienced agricultural export growth.

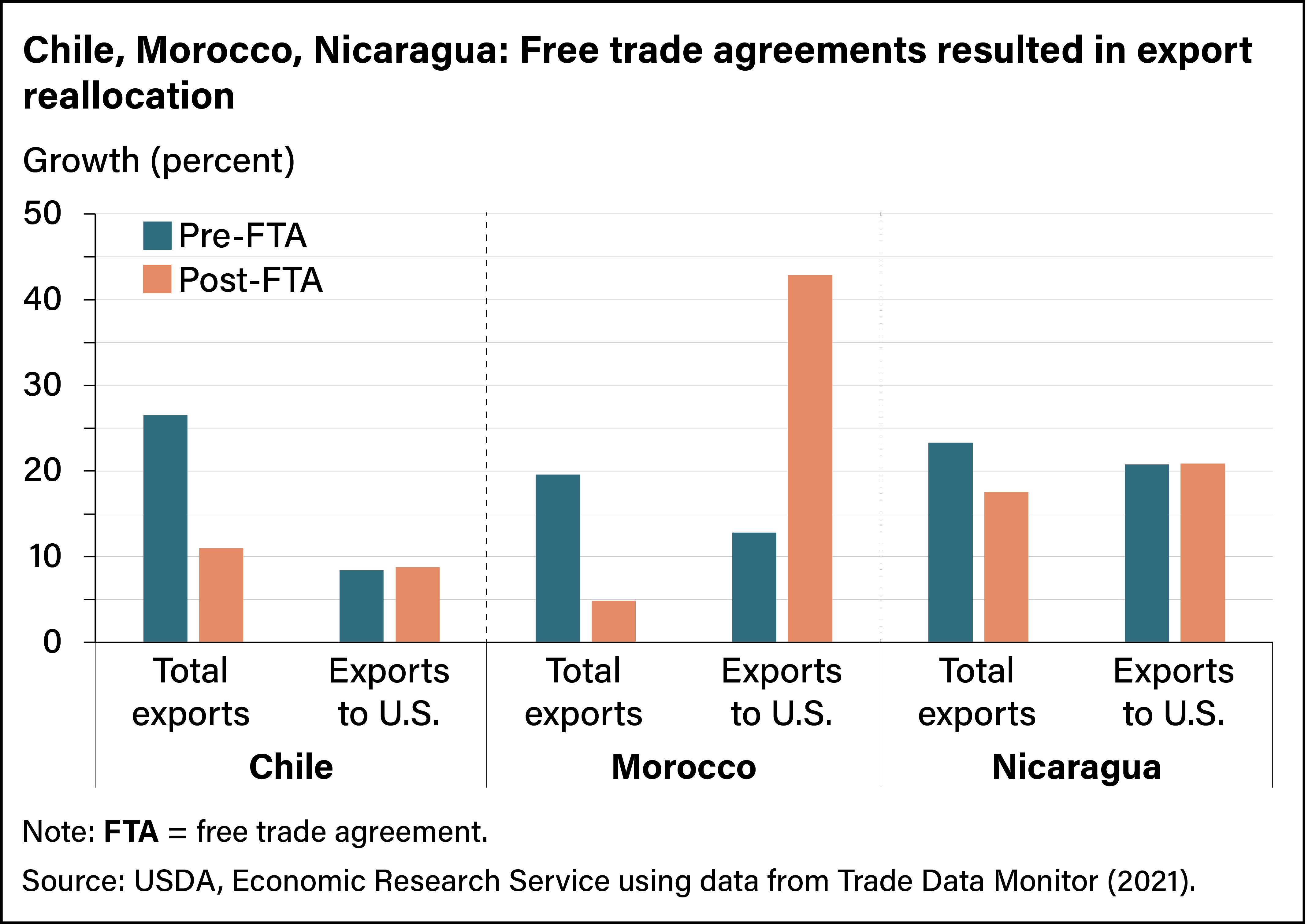

Export reallocation (Quadrant 2). In this category, agricultural exports to the United States accelerated, but total exports slowed for the partner country. Researchers concluded that the increase in exports to the United States came at the expense of existing trade that was reallocated from other countries. This occurred for Morocco, Nicaragua, and Chile. Exports to the United States accelerated after their FTA was implemented, but total exports slowed or stagnated. That suggests these countries reallocated existing exports.

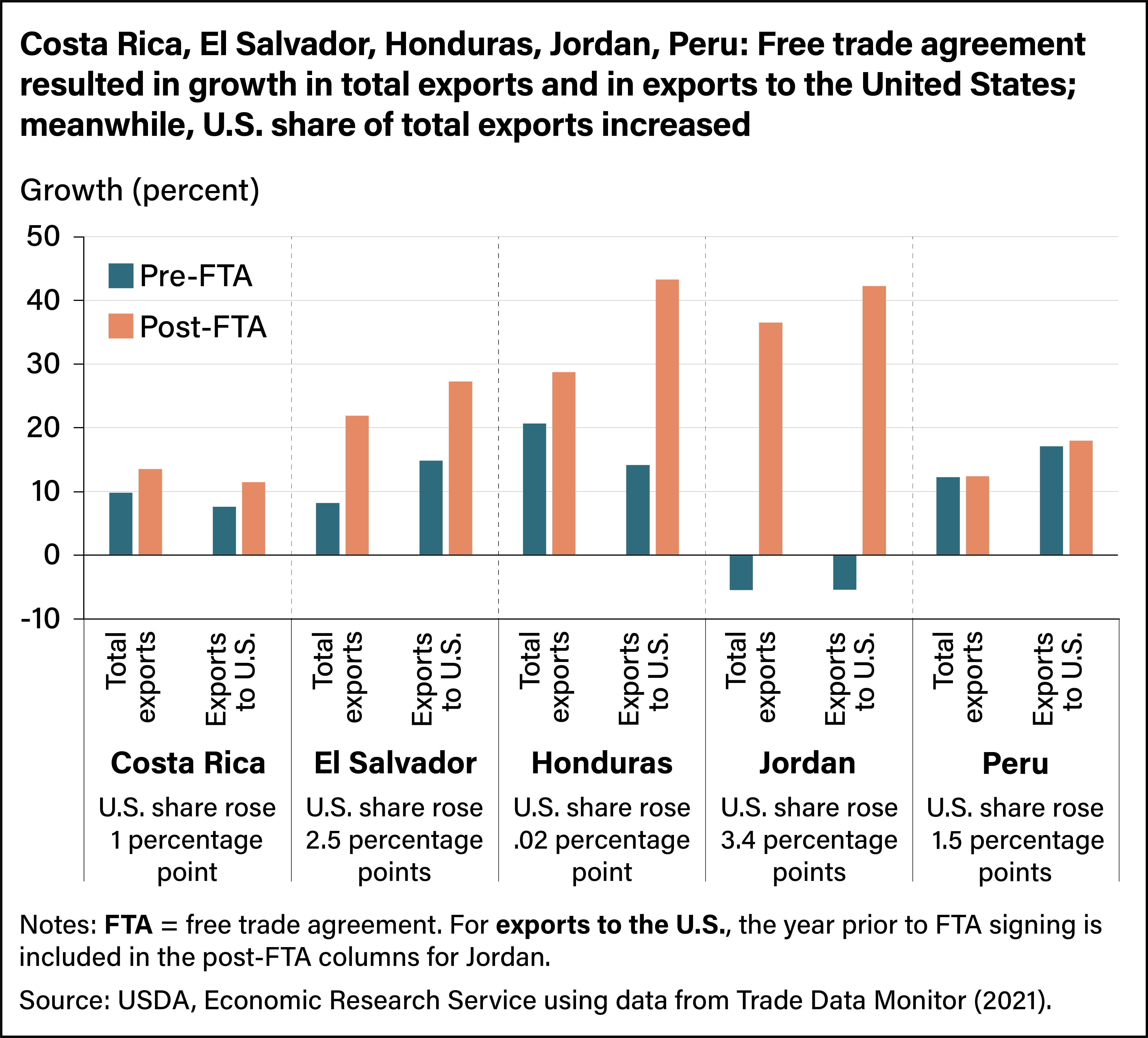

Both export growth and reallocation (Quadrant 3). Under other free trade agreements, total exports and exports to the United States both accelerated in the 5 years following FTA implementation. Because exports to the United States increased without corresponding decreases of exports to other countries, researchers looked at the change in the U.S. share of a partner’s total agricultural exports to determine whether export growth and reallocation occurred (see chart below). This was the case for Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Jordan, and Peru. In those countries, the U.S. share of agricultural exports increased after FTA implementation.

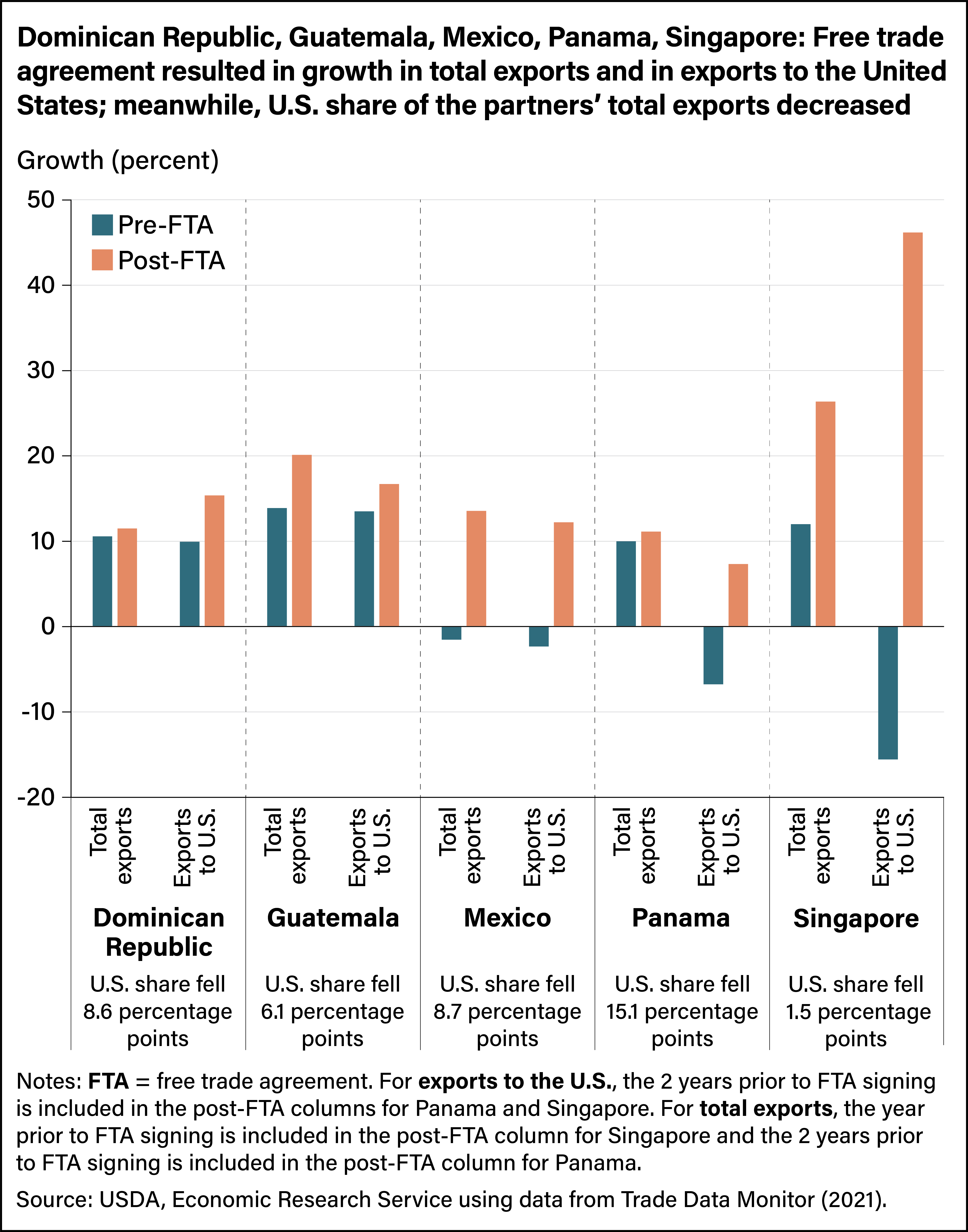

Conversely, the U.S. share of agricultural exports from the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, and Singapore fell after their corresponding trade agreements (see chart above). These countries belonged to simultaneous or multilateral trade agreements that allowed for additional export opportunities outside the United States. Though the U.S. share of agricultural exports fell, exports to the United States accelerated so these countries may have diverted exports from non-FTA partners to the United States but at a lower rate than for other FTA partners. Researchers concluded that exports to the United States from the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, and Singapore increased and were reallocated from non-FTA partners following their agreement implementation.

Neither export growth nor reallocation (Quadrant 4). Under some free trade agreements, total exports and exports to the United States both slowed after implementation of the FTA. For exports to “slow,” the change could be positive or negative, as long as the average annual change in exports was slower post-FTA then it was before the agreement.

Canada’s total agricultural exports and exports to the United States both slowed after implementation of its FTA, as Canada showed neither growth nor a reallocation of agricultural exports. Researchers suggested this could be the result of economic shocks unrelated to the FTA. However, they also concluded that Canada, a developed country, may have shifted production away from agriculture and toward other sectors of the economy. This shift in production would have been exacerbated by the North American Free-Trade Agreement (NAFTA) if the United States and Mexico had an advantage over Canada in agricultural production. In that case, Canada would have increased agricultural imports from Mexico and the United States and boosted production and exports of goods in other sectors of the economy.

This article is drawn from:

- Ajewole, K., Beckman, J., Gerval, A., Johnson, W., Morgan, S. & Sabala, E. (2022). Do Free Trade Agreements Benefit Developing Countries? An Examination of U.S. Agreements. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-240.

You may also like:

- Beckman, J. (2021). Reforming Market Access in Agricultural Trade: Tariff Removal and the Trade Facilitation Agreement. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-280.

- Beckman, J., Gale, F. & Lee, T. (2021). Agricultural Market Access Under Tariff-Rate Quotas. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-279.

- Gomez, M.I., Puerto, S., Zahniser, S. & Li, J. (2021). U.S. Agricultural Exports to Colombia: Rising Sales in Response to Trade Liberalization and Changing Consumer Trends. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. AES-118-01.