Food Loss: Why Food Stays On the Farm or Off the Market

- by Gregory Astill

- 3/2/2020

Highlights

- Reducing food loss in produce—when fruits and vegetables are not eaten by consumers—is a priority for the USDA and other national and international food and environmental entities.

- Food may be left unharvested in a field or not sold by a distributor for a variety of economic reasons, including price volatility, labor cost, lack of refrigeration infrastructure, consumer preferences, quality-based contracts, and various policies related to produce.

- Each action to reduce produce food loss comes at a cost. When reducing food loss is considered alongside goals like improving farm income, industry adoption of food loss initiatives may be more likely.

Why would a grower leave food unharvested in the field?

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture's (USDA's) Economic Research Service (ERS) identified a variety of economic factors that influence growers or distributors in their decisions regarding food loss, including:

- price volatility,

- labor cost and availability,

- lack of refrigeration infrastructure,

- aesthetic standards and consumer preferences,

- quality-based contracts, and

- various policies related to the harvest and marketing of fresh produce.

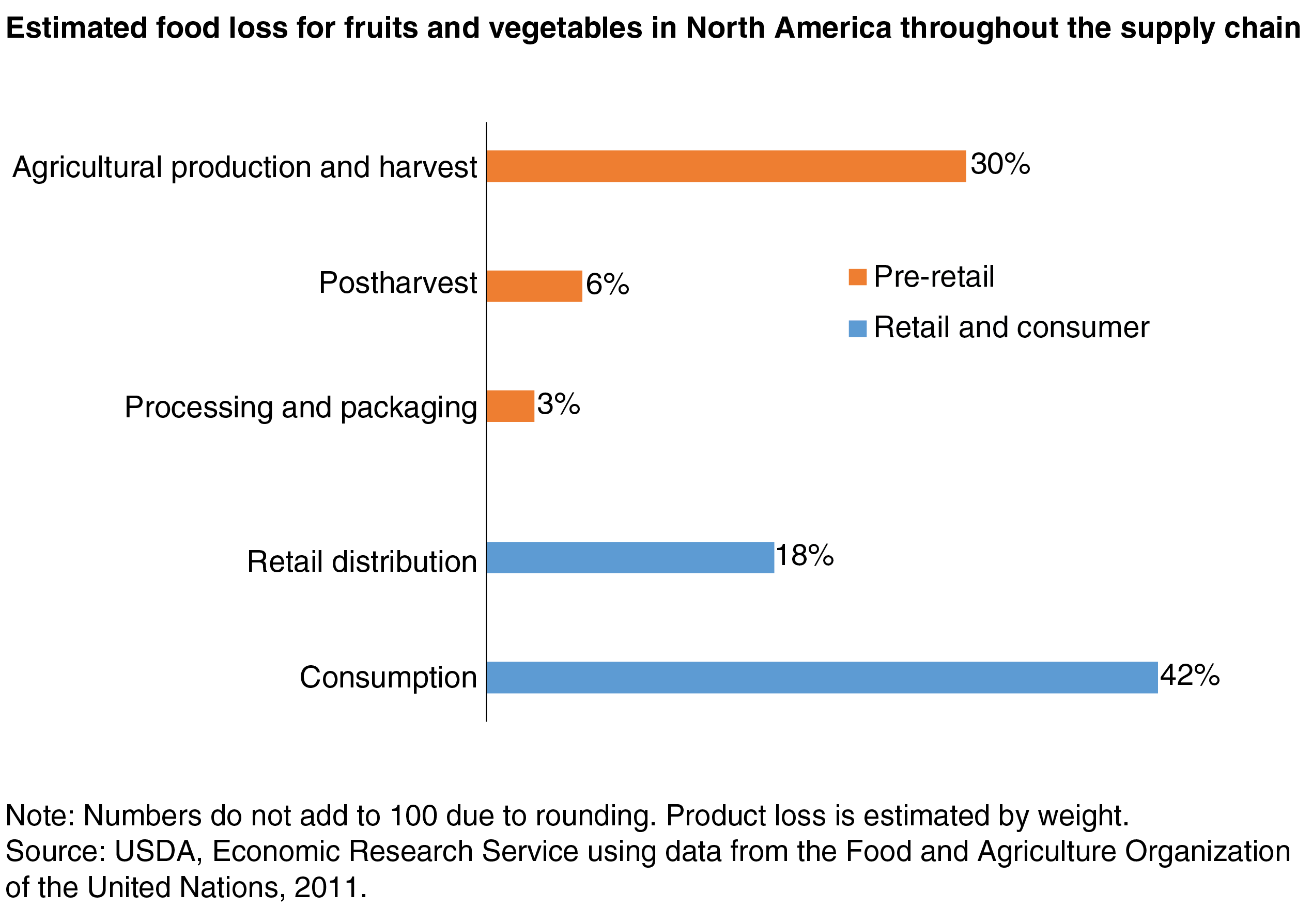

ERS estimates that $161.6 billion of food at the retail and consumer stage of the supply chain goes uneaten yearly. Through the entire supply chain, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that 30 percent of global food loss occurs at the agricultural production and harvest stage, 6 percent at post-harvest, 3 percent at processing and packaging, 18 percent at retail and distribution, and 42 percent at consumption. While the causes of food loss at the end stages of the supply chain have been well studied, the causes of loss on the farm and in early distribution stages have not. Food loss as it relates to fresh fruits and vegetables is especially challenging because these foods are highly perishable.

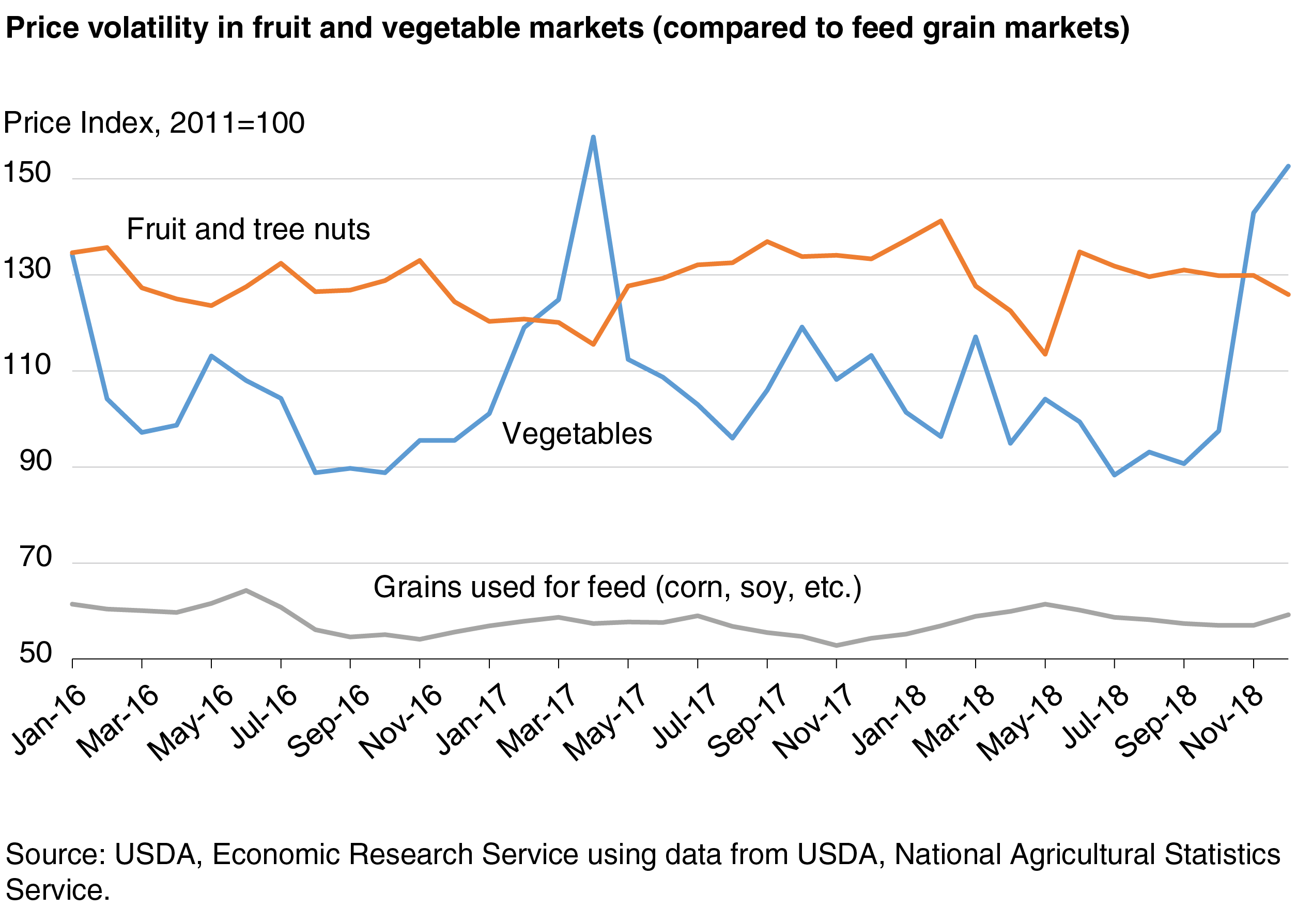

Price Volatility

Prices of fresh produce can quickly rise or fall, especially when compared to other agricultural products. There are times when it may become unprofitable to move produce into the market because prices fall below the cost of harvest, processing, or shipping. When prices rise, growers harvest more intensively (either by hiring more labor or by lowering product thresholds) and may have the incentive to send lower cosmetic-quality product to market, which can then be subject to increased loss further along the supply chain.

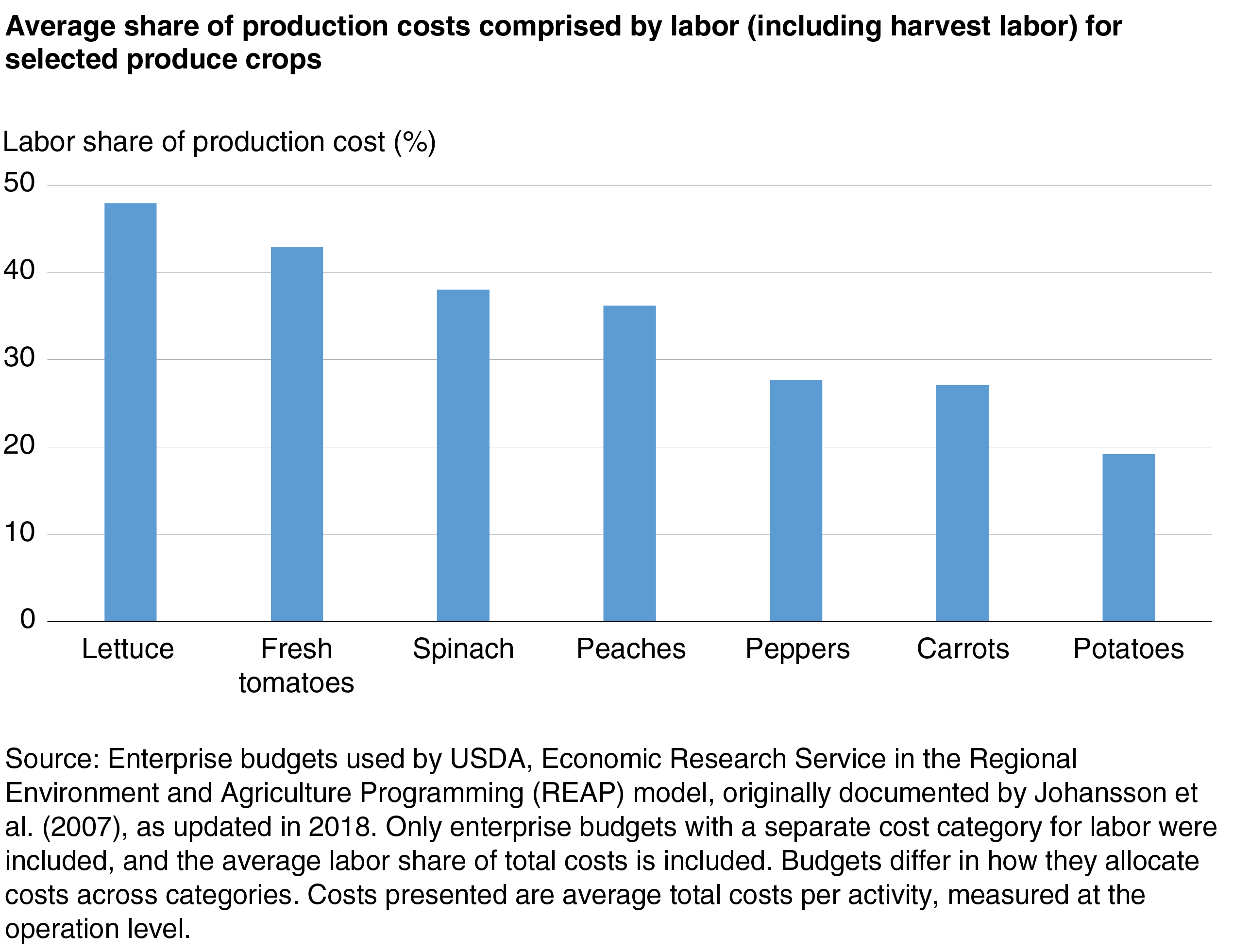

Labor Cost and Availability

Labor is a relatively high share of the cost of growing and marketing fresh produce. Labor (including harvest labor) comprises nearly half of the share of production cost for lettuce and more than one-third for fresh tomatoes, spinach, and peaches. Rising wages and decreasing labor availability may combine to increase the costs to harvest the produce in a field. During times when harvest labor is costly, growers may abandon the crop before harvest or make other production and marketing decisions that directly affect levels of food loss.

Cold-Chain Infrastructure

Investments in infrastructure to keep produce cool until it gets to market, such as vacuum cooling refrigerated storage facilities, are large, with benefits often shared across multiple growers. Incurring these costs for crops that would command a lower price often is not profitable for a single grower.

Aesthetic Standards and Consumer Preferences

Produce that does not meet aesthetic or other requirements, at any stage in the supply chain, is likely to be rejected, either by commercial buyers or final consumers. Growers, shippers, and retailers make decisions about what to cull based on perceived consumer preferences; if sellers in any of these supply chain stages anticipate that a buyer will not accept certain produce, they do not harvest or accept such produce from earlier stages of the supply chain.

Quality-Based Contracts

Agreed-upon price and delivery date for product of a defined quality (i.e., contracting) may reduce some of the variability in price and seasonal availability that is otherwise inherent to produce markets. However, contracts may also contribute to food loss by acting as barriers to entry, such as for growers who have additional product that does not meet fresh market cosmetic standards—e.g., a blemished apple—but are not already contracted in a supply chain for processed products with less stringent cosmetic standards—e.g., applesauce.

Policy Constraints

Federal, State, and local policies, such as tax incentives for donating food, can support food-loss reduction, recovery, and recycling, but some policies may fail to address the underlying causes of loss. Moreover, some existing policies may unintentionally serve as barriers, such as restrictions on gleaning (the harvest of intentionally unharvested produce for the purpose of donation) or supply control through private-public marketing orders. Quality standards enforced through private and public marketing orders may also affect food-loss rates.

Challenges to Estimating Food Loss on the Farm and in Pre-Retail Stages

Gathering data on a hard-to-define concept like food loss from a highly diverse group of fruit and vegetable growers, processors, and shippers is a challenge for researchers. While consistent, reliable, national estimates of food loss on the farm and at the pre-retail level constitute a significant investment, some opportunities to reduce food losses and improve farm income have emerged.

Reducing food loss, like any singular focus in a complex system, does not occur in a vacuum and each action comes at a cost. Food loss reduction may be greatest when considered alongside other competing factors for the individual grower, processor, retailer, and consumer. If reducing food loss takes away resources devoted to farm profitability, for example, it is unlikely that any grower would choose to participate. However, if reducing food loss is considered alongside more traditional goals like improving farm income, industry adoption of food loss initiatives may be more likely. Additionally, how the issue is framed (e.g., as a distribution problem, a way to feed hungry people, or a path to increase farm profit) may lead to different mitigation strategies that produce different results.

There are emerging retail markets and opportunities that can both alleviate food loss and improve grower’s income, as shown by consumer interest in “ugly” or “imperfect” produce. As the conditions for food loss are multifaceted, so, too, are the strategies that alleviate that loss and improve grower welfare. Collecting and analyzing nationally representative data could identify which of the potential driving factors are most significant and highlight the opportunities to most substantially reduce food loss.

This article is drawn from:

- Minor, T., Astill, G., Raszap Skorbiansky, S., Thornsbury, S., Buzby, J.C., Hitaj, C., Kantor, L., Kuchler, F., Ellison, B., Mishra, A.K., Roe, B. & Richards, T.J. (2020). Economic Drivers of Food Loss at the Farm and Pre-Retail Sectors: A Look at the Produce Supply Chain in the United States. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-216.

You may also like:

- Food Availability (Per Capita) Data System - Food Loss. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.