2018 Farm Act Retains Conservation Programs But Could Reduce Payments for Land Retirement

- by Roger Claassen, Daniel Hellerstein and Steven Wallander

- 12/2/2019

Highlights

- The new Farm Act (which covers 2019-23) continues all five major USDA conservation programs, but also makes subtle changes that could shift policy focus away from support for farm-wide conservation.

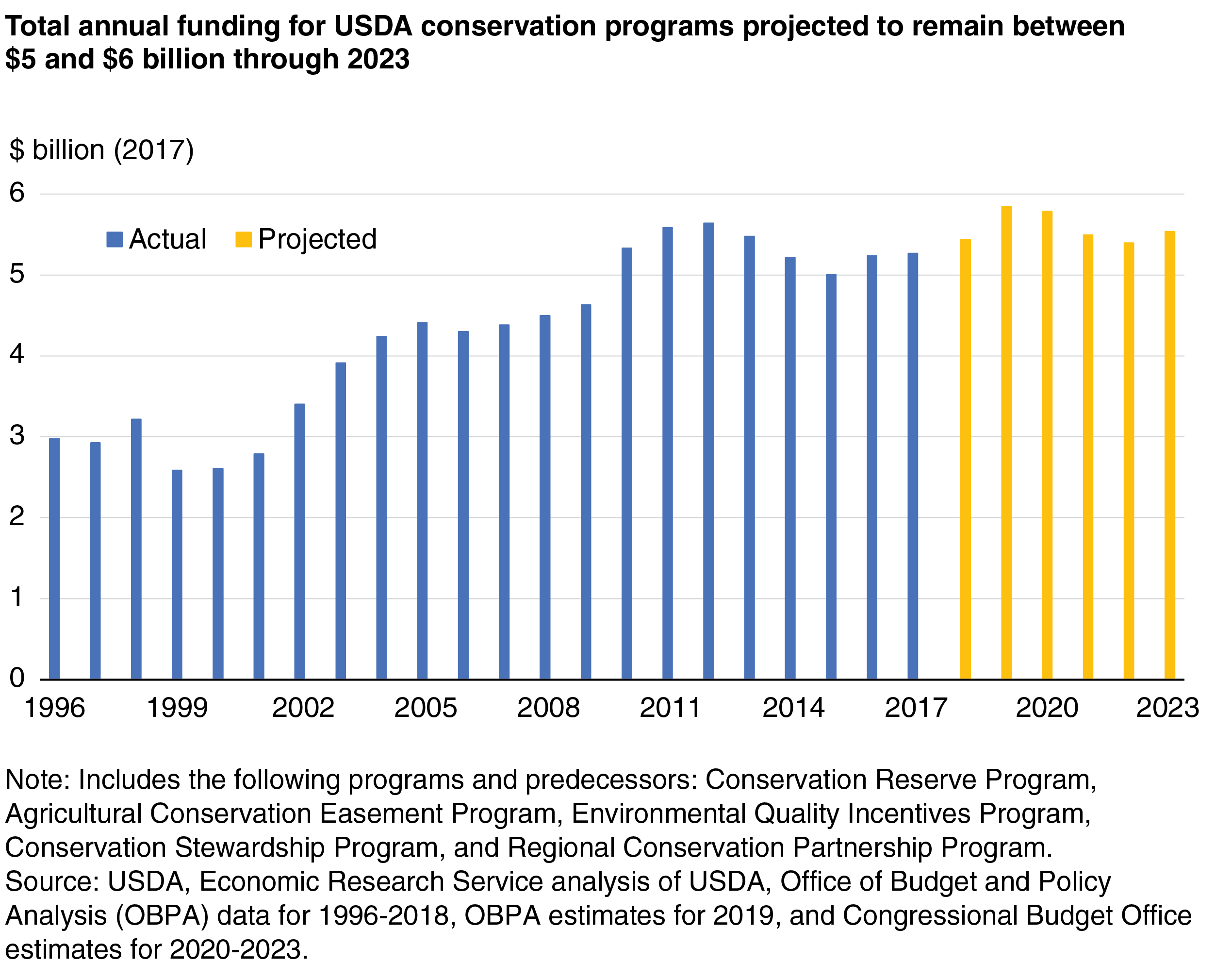

- Overall conservation spending is roughly similar to what it was under the 2014 Farm Act, projected to remain between $5 and $6 billion through 2023.

- New constraints on rental payments from the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) could lead to lower average payment rates, which could also lead to lower enrollment incentives.

Under the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (also known as the 2018 Farm Act), agricultural conservation policy retains most of the programs under the previous Farm Act of 2014. Unlike the 2002, 2008, and 2014 Farm Acts—all of which involved some reconfiguration of programs—the 2018 Act continues all major conservation programs and makes only modest changes in program funding. The five largest agricultural conservation programs continue to account for a large majority of mandated conservation spending, while overall spending levels are projected to be slightly higher than they would have been under the 2014 Farm Act.

Embedded within the bill, however, are changes that could have far-reaching effects on the conservation incentives offered to farmers and ranchers. Specifically, the 2018 Farm Act sets funding for the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) at $700 million in fiscal year (FY) 2019, lower than in recent years, and gradually increases funding to $1 billion per year by 2023. In contrast, the new Farm Act increases funding for the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). Specifically, the 2018 Farm Act shifts funding away from the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) and toward the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). The new Act is also likely to decrease the average size of annual payments available to producers in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which could reduce incentives for landowners to offer land for CRP enrollment and lessen the program’s role in the land market.

Conservation Funding To Increase Slightly

Under voluntary incentive programs, producers receive financial and technical assistance to take actions that conserve resources or reduce the environmental effects of agricultural production. These five programs are the backbone of agricultural conservation policy:

- The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) provides annual rental payments to landowners who voluntarily retire environmentally sensitive cropland for 10 to 15 years or who reenroll earlier contracts subject to the availability of signup opportunities.

- The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) provides financial assistance to farmers who adopt or install conservation practices on land in agricultural production.

- The Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) supports ongoing and new conservation. To be eligible, farmers and ranchers must demonstrate a high level of stewardship and agree to further improve conservation over their whole farm or ranch during the life of the CSP contract (5 years).

- The Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) provides long-term or permanent easements for preservation of wetlands and the protection of agricultural land (cropland, grazing land, etc.) from commercial or residential development.

- The Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) engages partners, often environmental or agricultural non-governmental organizations, to address resource conservation or environmental problems on a regional or watershed scale. By pooling together Federal and non-Federal resources, RCPP provides financial and technical assistance.

Under the 2002 and 2008 Farm Acts, spending on farm bill conservation programs grew rapidly. Over the course of a single decade, real (inflation-adjusted) spending grew by more than 80 percent—from less than $3 billion in FY 2001 to roughly $5.5 billion in FY 2011. Conservation spending leveled off under the 2014 Farm Act (FY 2014-18), settling at levels that were higher on average than under the 2008 Farm Act (FY 2008-13), but lower than peak spending in fiscal years 2011 and 2012. Under the 2018 Farm Act, which covers FY 2019-23, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects mandatory spending that is slightly higher than spending projected under an extension of previous 2014 Farm Act programs. Although funding for farm bill conservation programs is mandatory (annual appropriations are not required to fund these programs), spending on these programs in future years is subject to congressional review and, under past farm acts, sometimes has been reduced.

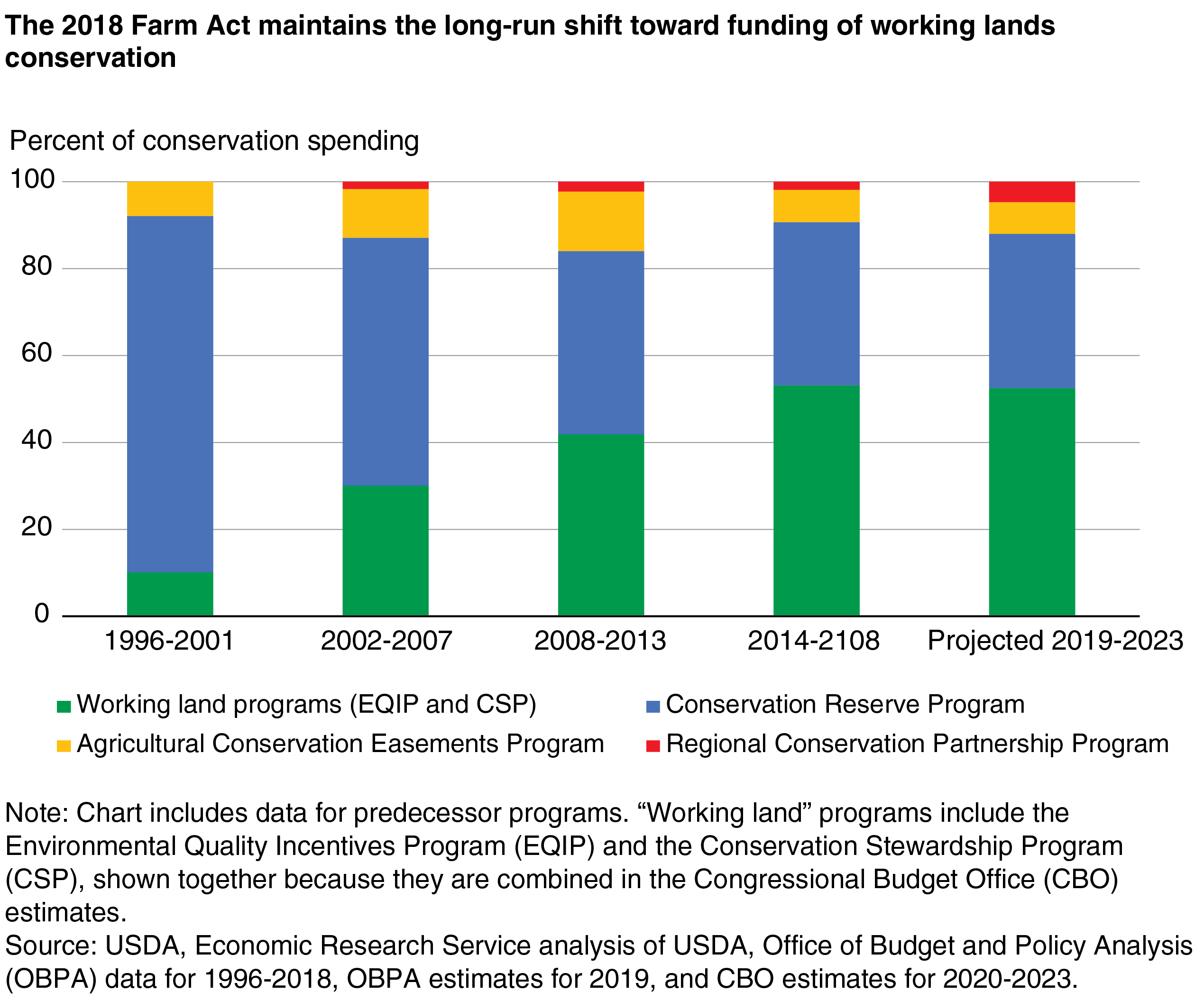

Funding changes over the last decade have resulted in a “rebalancing” of conservation effort from programs largely designed to move land out of production (e.g., CRP) to programs designed to support farmers who use resource-conserving practices on land in crop and livestock production (e.g., EQIP and CSP). The rapid increase in conservation spending between 2001 and 2011 was accomplished largely through increases in such “working land” programs. Programs like EQIP and CSP can and do fund a wide range of conservation practices. Widely supported practices include winter cover crops, brush management, grass waterways, nutrient management, irrigation water management practices, conservation tillage, and terraces (for soil conservation). The practices applied on any given farm or field depend on type of agricultural production, climate, topography, producer preferences, and other factors.

Three programs, CRP, EQIP, and CSP, account for approximately 88 percent of conservation spending mandated by the 2018 Farm Act. While the share of conservation funding for working lands was increased through the 2002, 2008 and 2014 Farm Acts, spending projections suggest that working land programs will receive 53 percent of conservation spending under the 2018 Farm Act (2019-23), nearly identical to the proportion under the 2014 Act.

Within the working land category, however, the new Farm Act shifts funding away from CSP and toward EQIP. CSP supports farms that have already met certain conservation thresholds to maintain and enhance existing conservation practices and expand conservation efforts using a comprehensive, farm-wide approach. EQIP is available more broadly (there are no minimum conservation requirements for program eligibility and no payments provided for continued adoption of existing practices), offering farmers and ranchers a more “a la carte” approach. For example, EQIP may fund anything from a single practice addressing a single resource concern to broader, more comprehensive farm-level plans. The CBO baseline (spending under a continuation of programs in the previous Farm Act) projected average annual spending of roughly $1.75 billion for each program during FY 2019-23. Under the 2018 Act, CSP spending (for new contracts) is limited to $700 million for FY 2019, increasing to $1 billion by FY 2023, both a decline from the $1.32 billion of CSP funding in 2018. In contrast, EQIP funding held steady initially, going from $1.76 billion in FY 2018 to $1.75 billion in FY 2019, and then increases gradually to $2.025 billion in FY 2023.

CRP Participation Incentives To Decline

Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) funding is projected to be roughly $2 billion per year over the course of the new farm bill (according to CBO projections). Under CRP, producers who agree to place marginal or environmentally sensitive cropland in grass or tree cover for 10-15 years can receive benefits, such as annual rental payments, cost-sharing, and other incentives.

The 2018 Farm Act increases CRP’s overall acreage cap from 24 million to 27 million acres, but also includes changes that are likely to reduce the size of annual rental payments to participants. The new limitations are designed, at least in part, to reduce per-acre costs of enrolling land in CRP and to limit the extent to which CRP is competing with farm operators who may be looking to rent the same cropland. Lower payments may also make it more difficult to maintain and expand CRP acreage, excluding some land with high environmental benefits or more beneficial practices that could have been enrolled when annual payments were higher.

USDA establishes parcel-specific “soil rental rates” (SRRs) that are, with some exceptions, the maximum annual rental payment that can be received under CRP contract. SRRs are designed to control program cost and ensure that CRP payment rates are in line with local land-rental markets and reflect variations in the productivity and rental value of land. SRRs are based largely on county-average cash rental rates for non-irrigated cropland, with adjustments for potential inflation and individual parcel characteristics. In some years, an inflation factor of 10 percent is added to the county-average cash rental rate to account for likely inflation over the 10-15 year period of a CRP contract, and the result is set as the county-average SRR. Parcel-specific SRRs start with the county-average SRR and then incorporate other adjustments, primarily for land productivity that is significantly higher (or lower) than average. In addition, parcels that enroll through continuous sign-up periods, which operate on a first-come first-served basis rather than through the competitive auction of the general signup, may receive CRP rental payments above their SRRs for practices that yield especially high environmental benefits.

Under the 2018 Farm Act, two provisions could push CRP rental payments down. The first would limit county-average SRRs to no more than 85 percent (general signup) or 90 percent (continuous signup) of the county-average, non-irrigated cropland cash rental rate (CRR). In the most recent general signups (45 in 2013 and 49 in 2016), county-average SRRs were set at 110 percent of the CRR, following the inflation adjustment. Under these new limits, SRRs could be significantly lower. The county-average SRR for continuous signup could be 90 percent of the CRR rather than 110 percent, while the general signup rate could be 85 percent rather than 110 percent of the CRR. How parcel-specific SRRs established under the new Farm Act compare to past ones will depend on how estimated county-average rental rates evolve over time and how county-average SRRs are adjusted for productivity or other factors.

For continuous signup contracts, which have often used signup incentive payments to increase participation rates, the 2018 Farm Act also mandates a signup incentive payment equal to 32.5 percent of the first annual rental payment. Assuming a 10-year contract and a discount rate of 5 percent, ERS researchers estimated that the incentive payment would exactly offset a 4-percent decline in present value of annual rental payments over a 10-year contract, discounting future payments at 5 percent. The incentive would not be large enough to fully offset a 10-percent decline in the present value of the rental rate.

The second farm bill provision that could lower CRP payments applies only to land that has already been under CRP contract. For this land, the annual rental payment would be limited to no more than 85 percent (general signup) or 90 percent (continuous signup) of the county-average cropland rental rate. If this limit is applied stringently, annual rental payments could not exceed these limits, even for relatively high-productivity land that could be assigned a higher-than-average SRR due to parcel-specific productivity adjustments or high-priority continuous signup practices that often have maximum payment rates above their SRR. Under the 2018 Farm Act, this provision may be waived (on a case-by-case basis) for the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP).

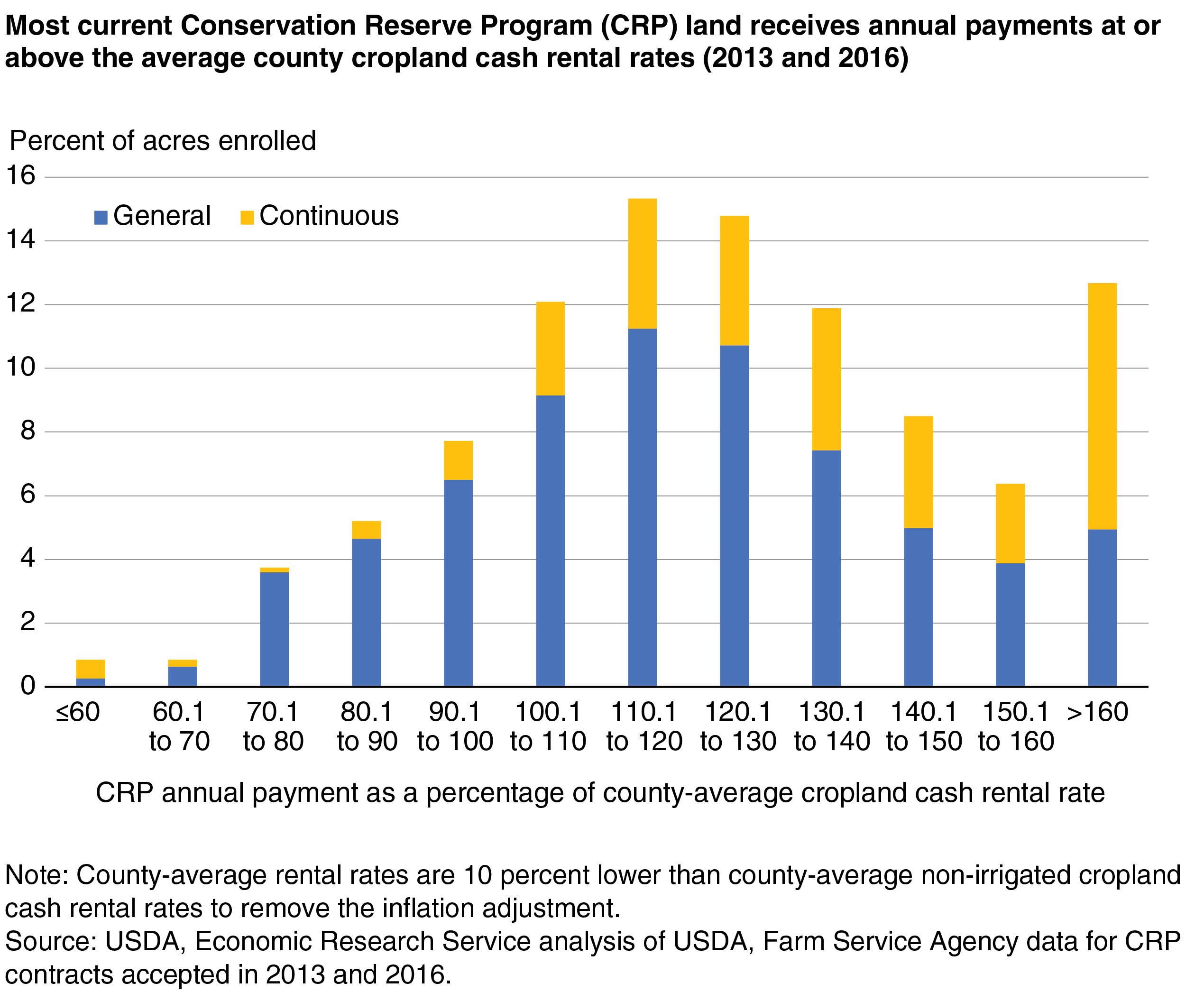

ERS researchers looked at the relationship between actual rental payments and the county-average rental rate (without the inflation adjustment) for land that was re-enrolled in CRP during 2013 and 2016. These years were selected because they include the two most recent CRP general signups. Re-enrolled land accounted for about 60 percent of CRP enrollments over this period. CREP contracts were excluded because the CRP limitations mentioned in the previous paragraph could be waived under CREP.

While this analysis cannot predict the specific effect of the new Farm Act provision on future CRP rental rates, it does suggest that the provisions, if they had been in force, could have had a significant impact on annual rental payments in past signups. During the 2013 and 2016 signups, less than 20 percent of previously enrolled acres had an actual annual rental rate that was lower than the county-average rental rate. Lower annual rental rates could reflect the enrollment in either general or continuous signup of land with productivity that was lower than the county average. In a general signup, when enrollment is competitive, lower rates could also reflect the effects of bidding down rental rates. Landowners who offer to take less than the maximum payment improve their chances of being selected for CRP contracts. CRP offers are ranked for acceptance using an Environmental Benefits Index that combines measures of expected environmental benefits and the cost of the contract.

For 80 percent of previously enrolled land, annual rental payments were above the CRR. For these parcels, annual soil rental rates could have been higher than CRR for a number of reasons, such as:

- County-average SRRs were set at 110 percent of the CRR.

- Higher annual rental rates could reflect the enrollment in either general or continuous signup of land with productivity higher than the county average.

- In continuous signup, payments above the SRR were allowed for some practices that may yield high environmental benefits.

If annual rental payments on previously enrolled land were set at 85 percent of the county-average rental rate for general signup or 90 percent for continuous signup, annual rental rates for a large share of re-enrolling land could be significantly lower. Had these limits been in effect for 2013 and 2016, rental rates would have been limited to a rate that is at least 30 percent lower than actual rental payments for roughly 40 percent of re-enrolling land. For example, land with an annual rental payment of $120 per acre, located in a county where the average rental cropland rental rate is $100, would have been limited to $85 (85 percent of $100) upon re-enrollment, a decline of almost 30 percent.

Many factors are considered in establishing upper limits on CRP annual payments. USDA policy regarding some of these factors (e.g., productivity adjustments to determine field-specific soil rental rates) can change over time. Our analysis suggests that limiting rental payments to 85 or 90 percent of the county-average soil rental rate (for general and continuous signup, respectively) could have had a significant effect on annual payments under previous signups, had it been in place during those signups. These estimates, however, should not be seen as a prediction of the impact on future CRP rental rates.

Conclusions

The broad outlines of U.S. conservation policy under the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 are much the same as those under the 2014 Farm Act. Some changes, however, could signal important shifts in the coming years.

The ultimate effect of shifting funds across working land programs is difficult to discern. The Conservation Stewardship Program and Environmental Quality Incentives Program serve different purposes and, to some extent, different producers. The allocation of funds could shift focus away from farms already engaged in and committed to conservation, particularly in terms of supporting and enhancing ongoing conservation efforts.

In the Conservation Reserve Program, findings suggest that reduced payments may make the program less competitive in the land market—particularly for re-enrollment of higher productivity land with above-average rental rates within counties and initial enrollment of contracts with higher cost practices, such as trees or riparian buffers. A less competitive CRP is also less likely to be a factor in cropland rental rates and could make additional land available to producers seeking to start or expand farming operations.

However, less competitive payments will make it more difficult to maintain and expand CRP acreage. Higher value land could be much more difficult to enroll and retain. High-value practices, which yield greater environmental benefits but are also more expensive to install, could also be discouraged by tighter limits on annual payments. This may be particularly true for practices in which benefits grow over time, such as the re-establishment of native vegetation for wildlife habitat.

This article is drawn from:

- 2018 Farm Bill. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Hellerstein, D., Vilorio, D., Ribaudo, M., Aillery, M., Bigelow, D., Bowman, M., Burns, C., Claassen, R., Crane-Droesch, A., Fooks, J., Greene, C., Hansen, L., Heisey, P., Hitaj, C., Hoppe, R.A., Key, N., Lynch, L., Malcolm, S., McBride, W.D., Mosheim, R., Nehring, R., Schaible, G., Schimmelpfennig, D., Smith, D., Sneeringer, S., Wade, T., Wallander, S., Wang, S.L. & Wechsler, S.J. (2019). Agricultural Resources and Environmental Indicators, 2019. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-208.

- Hellerstein, D. M., “The US Conservation Reserve Program: The Evolution of An Enrollment Mechanism,” . (2017). Land Use Policy 63: 601–610.

You may also like:

- Claassen, R. (2012). The Future of Environmental Compliance Incentives in U.S. Agriculture. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-94.

- Wallander, S., Claassen, R., Hill, A. & Fooks, J.R. (2019). Working Lands Conservation Contract Modifications: Patterns in Dropped Practices. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-262.