China’s Agricultural Investment Abroad Is Rising

- by Fred Gale and Elizabeth Gooch

- 4/24/2018

Highlights

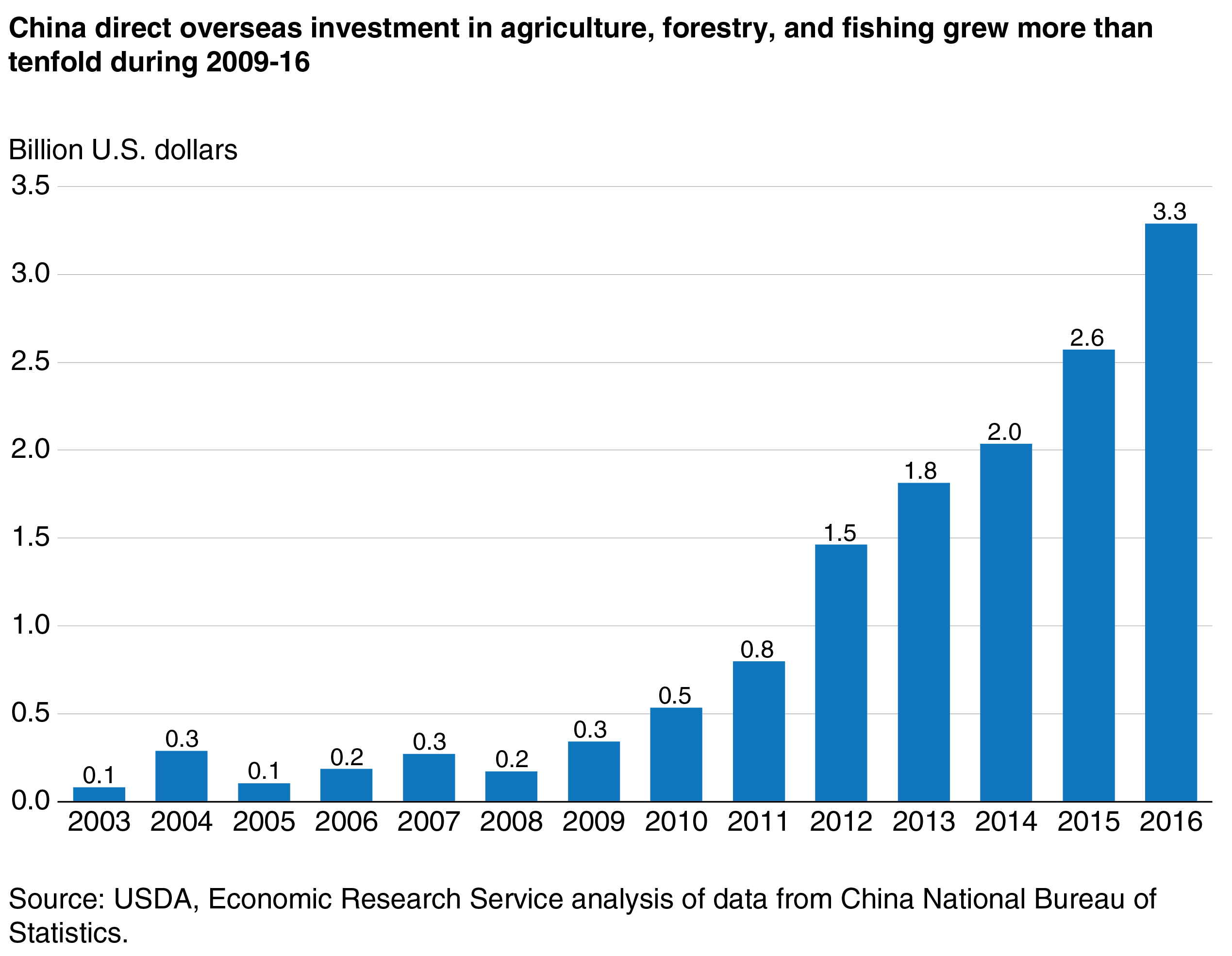

- China’s agricultural investment abroad grew more than tenfold in less than a decade.

- The growth parallels China’s emergence as a major importer of agricultural commodities.

- The focus of investments are shifting from farming and raw materials to business acquisition.

China’s need for agricultural resources and technology and the country’s considerable financial clout are driving rapid growth in Chinese investment in agriculture and food sectors abroad. The trend reflects the growing global ambitions of Chinese companies, and it is attracting the attention of business and government leaders around the world.

According to Chinese investment statistics, overseas ventures in agriculture, forestry, and fisheries soared from $300 million in 2009 to $3.3 billion in 2016. But these totals understate the magnitude of Chinese agricultural-focused foreign assets because the statistics exclude the acquisition of food processing and trading companies classified in manufacturing and service sectors. A more complete count issued by China’s Ministry of Agriculture said the country had over 1,300 agricultural, forestry, and fisheries enterprises with registered overseas investments of $26 billion, at the end of 2016.

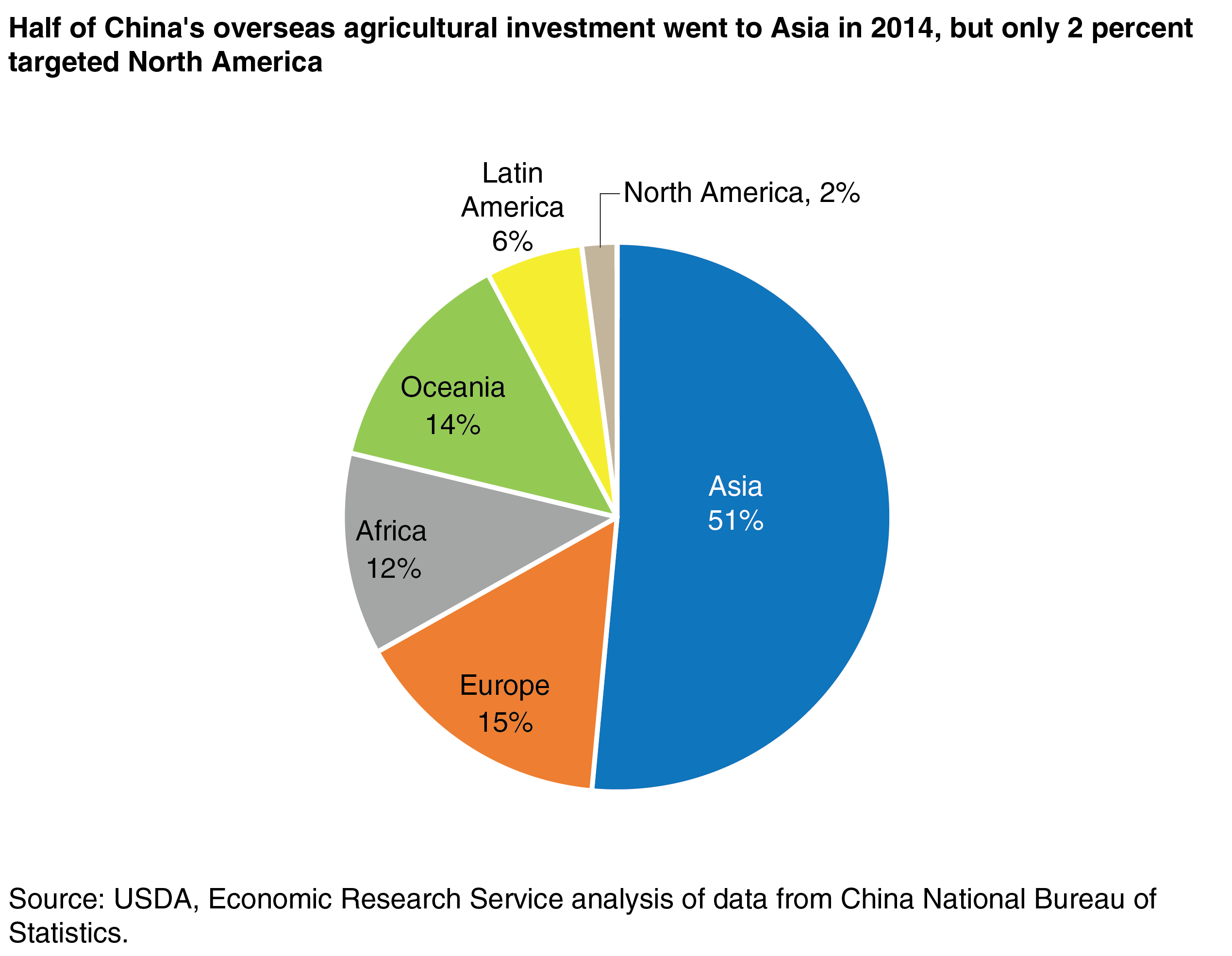

An initial wave of investments during 2004-12 was focused mainly on crop production, fishing ventures, and acquiring raw materials for the Chinese market. Most such ventures have targeted eastern Russia and neighboring Asian countries, attracted by relatively cheap, underutilized land. Chinese investments in Southeast Asia have focused on tropical crops like palm oil, cassava, sugar, fruit, and lumber, prompted by strong domestic demand and a regional free trade agreement with the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). Asia accounts for about half of China’s foreign investment in agriculture, forestry, and fishing.

More recently, some Chinese companies and officials have shifted the thrust of their strategy from farming overseas to acquiring established agribusiness companies based in Europe, North America, and Oceania. These include ChemChina’s $43-billion acquisition of Syngenta, a Swiss farm chemical and seed company, Shuanghui International's purchase of U.S.-based Smithfield Foods, and China National Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs Corporation’s (COFCO) purchase of two major agricultural trading companies—Noble Agri and Nidera. Chinese companies have also acquired companies or formed joint ventures in New Zealand and Australia, focused on meeting China’s growing demand for dairy, beef, and lamb.

China’s Strategic Considerations as an Agricultural Importer

The surge of agricultural investment reflects an alignment of interests between Chinese companies and political leaders as China’s imports of agricultural products grow. The Ministry of Agriculture reported that agricultural imports exceeded $125 billion for 2017, up from $41 billion 10 years earlier. The growth reflects greater import volume of particular commodities like soybeans and pork as well as a broadening menu of imported commodities. Chinese consumers’ escalating demand for product variety—from staples like rice and wheat to premium products like olive oil and infant formula—stimulates commercial investments in land, brand names, and technology aimed at profiting from market growth. At the same time, the Chinese Government seeks to steer investors toward ventures that achieve national goals by offering various incentives, arranging deals, and setting up strategic plans.

As Chinese authorities have loosened national food self-sufficiency objectives, they have encouraged companies to gain greater control over the supply chain for imported agricultural products. Their “two markets, two kinds of resources” strategy calls for China’s demand for agricultural commodities to be met by a combination of domestic and foreign supplies. The strategy encourages Chinese companies to engage in each link of the supply chain for imported commodities to earn profits and gain influence over prices.

The strategy is reflected in encouragements to invest abroad by various documents and articles issued by Chinese leaders. For example, a series of annual “Number one documents” from China’s communist party authorities stating rural policy have contained increasingly specific strategies for investment. A general exhortation to invest in agriculture overseas, issued in 2007, was followed by an initial surge in overseas farming ventures. In 2010, authorities called for supportive policies to encourage investment abroad. The 2014 document included a more specific mandate to create large grain-trading conglomerates, designed to give Chinese companies greater control over oilseed and grain imports. That was the same year COFCO acquired Nidera and Noble Agri, making COFCO one of the largest trading companies in the world based on value of assets. The 2015 document specifically called for policies to support facilities, equipment, and inputs for agricultural production in foreign countries. The 2017 document broadened the encouragement to include all types of agricultural conglomerates. The 2018 document repeated the general endorsement of overseas investment and instructions to create multinational grain-trading and agricultural conglomerates.

The incorporation of agricultural investment into broader geopolitical objectives is reflected by the prominence of “One Belt One Road,” a recent Chinese development strategy for connectivity and cooperation among Eurasian Countries, in policy directives on agricultural investment contained in 2015-18 rural policy documents. In these documents, Chinese officials emphasize the role of agricultural investment, technical assistance, and agricultural trade as a crucial part of the initiative that targets agrarian countries in Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe for closer relations in trade and investment.

China’s aspiration to be a leader in international technical cooperation is reflected by an instruction to build agricultural technology parks overseas, issued in 2015. Early examples have been constructed in Tanzania and eastern Russia. Many projects associated with these initiatives appear to function both as foreign aid projects and as ventures giving Chinese companies access to agricultural raw materials.

| Year | Strategic statements related to foreign investment in agriculture |

|---|---|

| 2007 | Accelerate the agricultural foreign investment strategy. |

| 2010 | Set policies to support and encourage companies to invest abroad. |

| 2014 | Accelerate the agricultural foreign investment strategy. Foster large, internationally competitive grain and oils enterprises. |

| 2015 | Promote foreign science and technology demonstration parks. Implement policies to support facilities, equipment, and inputs needed for foreign agricultural production. |

| 2016 | Strengthen agricultural investment with countries along the “One Belt One Road” path and bordering countries and regions. Foster international grain traders and agricultural conglomerates. |

| 2017 | Support multinational agricultural businesses that are developing foreign production bases, processing, storage, and logistics focused on “One Belt One Road” objectives. Foster large internationally competitive conglomerates. |

| 2018 | Actively support agricultural foreign investment. Foster large, internationally competitive grain-trading and agricultural business conglomerates. |

| Note: Drawn from “Number one documents” issued by China’s central communist party committee that summarize rural policy priorities for the year. Translations from Chinese to English by USDA, Economic Research Service. | |

Many of China’s Investments Fall Short of Expectations

Rapid growth in investment does not necessarily mean success. Many of China’s overseas investments never reach their intended scale, and quite a few have been abandoned. While a handful of prominent ventures and acquisitions have benefited from bank loans or deals negotiated by political leaders, surveys by Chinese scholars have found that most overseas agricultural investors receive little Government assistance.

An agricultural park established in Laos by the Chongqing Municipal Government illustrates the disappointing results achieved by many projects. According to Chinese news media, the planned 5,000-hectare park was expected to produce flowers, aquaculture products, and other items, but it never grew beyond 50 hectares. While 200 Chongqing companies expressed interest in the Laotian park, only 4 actually invested. The most prominent business venture planned for the park in Laos intended to ship rice back to China. However, rice seeds brought from Chongqing proved unsuited to the local climate and soils. After several years, a viable hybrid variety was developed, but the company discovered that costs of transporting rice to China would be prohibitive. The company concluded that additional investment in irrigation and roads needed to make the park viable could not be justified. By 2013, the original four investors had pulled out of the project.

More recent investments by some of China’s largest agribusiness companies have also encountered difficulties. China’s Bright Group sold Weetabix 5 years after acquiring it, reportedly due to disappointing sales of its products in China. Both Bright and COFCO discovered financial irregularities in companies they had acquired.

China’s investment strategies and policies, however, are responding to problems and new priorities. Many companies have shifted from overseas farming to acquisitions of existing companies and assets in marketing and processing. To support investment, Chinese Government organizations are setting up training courses, information clearinghouses, and subsidized insurance and are upgrading ports of entry and building overseas agricultural technology parks.

Responding to concerns voiced by many countries experiencing Chinese investments, Chinese Government leaders have advised companies investing overseas to give more attention to building goodwill in the host country. One Chinese company provided financial support to a dairy research institute in New Zealand and another cofounded a food safety initiative in Australia to allay concerns about Chinese investment in those countries. Another strategy is to emphasize “win-win” projects that give poor farmers technical training and access to new markets. Mutual benefits of disseminating new techniques and opening new markets in exchange for greater raw material supplies is a theme of China’s agricultural investments in the regions of Asia and Africa. For example, a manufacturer of a traditional Chinese medicine derived from donkey skins sponsored an international conference on donkey breeding and farming as a strategy for fostering new suppliers in poor countries where raising the animals is still popular.

More Growth on the Horizon?

While China’s spending on foreign agricultural ventures appears large, it is modest compared with the country’s agricultural imports: In 2016, the country’s foreign agricultural investment equaled just 3 percent of the value of its agricultural imports that year. Moreover, agricultural investment has lagged behind other sectors in China’s foreign investment surge. Agriculture, forestry, and fishing accounted for about 1.7 percent of China’s foreign investment from 2012 to 2016. By comparison, agriculture’s share of China’s gross domestic product is about 9 percent.

More growth in Chinese investment appears to be forthcoming. Political leaders in China are endorsing agricultural investment as a core component of China’s One Belt, One Road initiative. More Chinese investments in Europe and North America could offer access to agricultural technology, processing, and logistical know-how to support China’s ambitions to modernize its domestic farming sector. China’s goals of gaining more control over supply chains for its imports and increasing its influence on global commodity prices could drive further investment in trading, logistics, and commodity markets.

China’s investments are likely to have impacts on global agricultural trade, just as a similar stream of Japanese investments did in earlier decades. Japanese companies played a role in Brazil’s emergence as a soybean exporter and China’s rise as an exporter of vegetables and poultry. Japanese agricultural trading companies have a prominent role in sourcing grains and oilseeds. There were concerns that Japan’s agricultural and food investment during the 1970s and ‘80s were a threat to U.S. agriculture. However, the United States remains the leading supplier of Japan’s agricultural imports, and Japan’s ownership of U.S. farmland and agribusiness remains modest.

China’s investments may influence patterns of trade at the margins, but resource scarcity, production capabilities, commodity prices, exchange rates, and other fundamentals will remain the dominant factors in the country’s growing agricultural imports. Nevertheless, China’s investments will create new opportunities and present new threats for particular industries, companies, and regions toward which they are targeted.

This article is drawn from:

- Gooch, E. & Gale, F. (2018). China's Foreign Agriculture Investments. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-192.