Land Acquisition and Transfer in U.S. Agriculture

- by Daniel Bigelow and Todd Hubbs

- 8/25/2016

Highlights

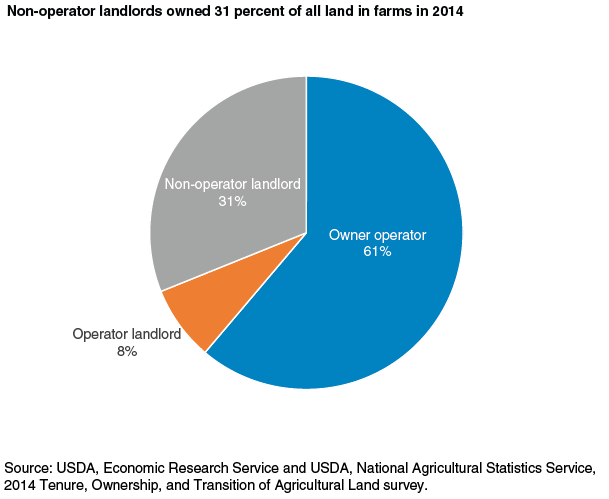

- Of the 911 million acres of land in farms in the contiguous 48 States, 31 percent is owned by entities who are not involved in farming and who rent the land to other farm operators.

- In 2015-19, just over 2 percent of land in farms is expected to be sold in an arm’s-length transaction in which the buyer and seller are not related.

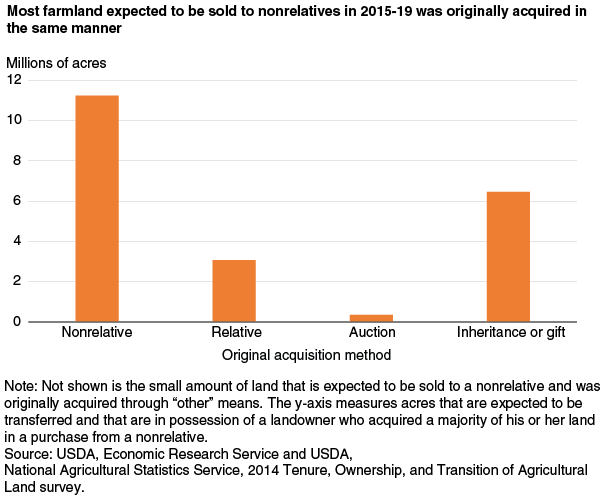

- Most land that will be sold to nonrelatives in the next 5 years was originally acquired in an arm’s-length transaction, suggesting that the supply of land available for purchase may not vary much over time.

As land is a primary input to farming, access to land is critical to starting and growing a farm operation. Given that land accounted for 81 percent of total asset value on U.S. farms in 2014, information on who owns land and the manner in which current operators acquired it can provide insights into the challenges involved with beginning or expanding a farm operation through land ownership. For example, if most land was acquired through an outright purchase from a nonrelative or auction, it would signal greater land availability than if most land were inherited. Information on the manner in which current landowners plan to transfer their land in the future may also signal potential opportunities, or barriers, to gaining access to farmland, particularly for beginning farmers and ranchers.

In the overall context of U.S. agriculture, landowners fall under three types: owner operators, operator landlords, and non-operator landlords. Owner operators are defined as farmers who own some or all of the land in their farm operation. Operator landlords are farm operators who rent some of the farmland they own to one or more other farm operators. Note that in terms of a single landowner entity, the owner operator and operator landlord categories are not mutually exclusive: a single agricultural landowner can operate some of the land (i.e., owner-operator) in addition to renting out a portion to other operators (i.e., operator landlord). Non-operator landlords are defined as agricultural landowners who rent land to one or more operators but are not, themselves, actively involved in a farm operation.

Of the total amount of farmland in the U.S. (911 million acres), 61 percent is owned by farm operators, 31 percent is owned by non-operator landlords, and the remaining 8 percent is rented from one operator to another. Although a sizable share of farmland is owned by non-operators, when accounting for those non-operators who either previously farmed or acquired land from a family member, 83 to 94 percent of all farmland is owned by a person or entity (e.g., corporation) with a current, former, or familial connection to the agricultural sector. The breakdown of land ownership is relevant to the topic of land accessibility because the manner in which landowners acquired and plan to transfer their land may vary across landowner entities. Specifically, non-operator landlords may have obtained their land through different channels than operators and may also have different objectives in terms of what they plan to do with their land in the future.

Land Acquisition Methods

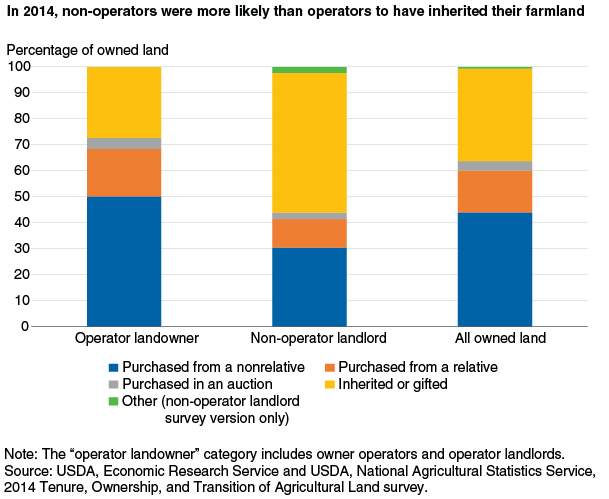

Access to land is often cited as a barrier to starting or expanding a farm operation. Although land accessibility is difficult to measure, one way of viewing its role as a barrier is to analyze the manner in which the current stock of farmland was acquired by its respective owners. For example, if the majority of farmland was acquired through inheritance or other forms of intergenerational within-family transfer, it would signal the presence of a potential barrier to those without any familial connections. In addition, the manner in which non-operators came into possession of their land provides useful information on whether these individuals have a personal connection to farming or if they acquired their land, possibly for investment purposes, via outright purchase.

Farmland may be acquired in a number of ways, including sales from both relatives and non-relatives, auction purchases, and inheritances or gifts. According to data from USDA’s 2014 Tenure, Ownership, and Transition of Land (TOTAL) survey, operator landowners (owner operators and operator landlords, collectively) purchased 50 percent of their land from non-relatives and 4 percent in auctions. In contrast, non-operator landlords acquired 30 percent of their land in purchases from non-relatives and 2 percent in auctions. Clearly, compared with their non-operator counterparts, operator landowners relied more heavily on arm’s-length market transactions (i.e., the buyer and seller were not related and were acting independently). The majority of non-operator-owned land, 54 percent, was inherited or received as a gift. Further, non-operator principal landlords (in individual and partnership ownership arrangements) who identify with having “never farmed”—which accounts for 45 percent of landlord survey respondents—are less likely to have purchased their land and more likely to have inherited or received their land as a gift. This implies that even though many non-operator landlords have had no direct experience with a farm operation, they may be acquiring land through a family or personal relationship to farming.

Land Transfers

The relatively advanced age of the U.S. farming population—about a third of principal farm operators in 2014 were at least age 65, compared with 12 percent of self-employed workers in nonagricultural businesses—has sparked interest in the manner in which land will be transferred to other landowners, including the next generation of farm operators. While it is not possible to determine how all farmland will be transferred, the TOTAL survey asked respondents how much of their land they anticipate transferring over the next 5 years using each of the following transfer methods: sell to a relative, sell to a non-relative, gift, place in a trust, or include in a will. Overall, 10 percent of all land in farms (93 million acres) is expected to be transferred between 2015 and 2019, 61 percent of which is owned by operator landowners.

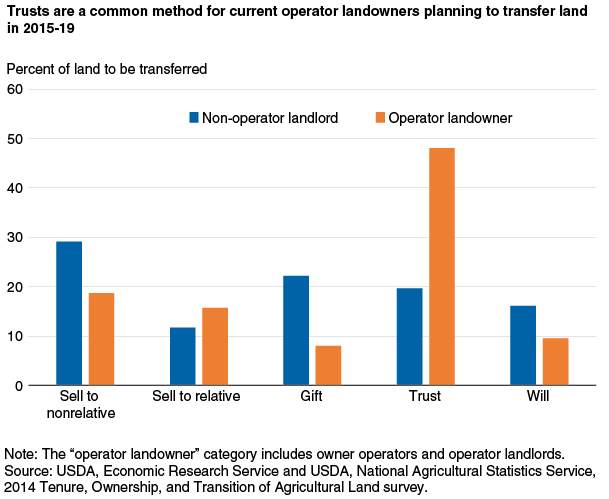

The market for farmland is often described as being “thin,” or having relatively few buyers and sellers, and, as a result, sales transactions take place infrequently. In 2014, less than 4 percent of all U.S. land in farms (34.3 million acres) was expected to be sold in the next 5 years. Furthermore, just over 2 percent of farmland (21.1 million acres) was expected to be sold to a nonrelative of the current owner, illustrating the potential challenges associated with acquiring land through an open-market purchase. Operating landowners and non-operating landlords vary in the manner in which they plan to transfer land. Selling land to a nonrelative was the most common method of transfer among non-operators (29 percent of all land they expected to transfer) and the second-most common transfer method among operator landowners (19 percent of land). Selling land to a relative was more common among operator landowners (16 percent of land owned) than among non-operators (12 percent of land owned).

One of the most common transfer methods, particularly among operator landowners, is putting land in trusts. Of all farmland expected to be transferred in 2015-19, trusts make up 48 percent of land owned by operators and 20 percent of land owned by non-operators. When a trust is established, the ownership of assets is transferred to the trust. However, the transferor, at least initially, may retain control of the assets as trustee of the trust. Thus, the establishment of a trust may or may not affect the use and availability of the land for rent or purchase. Establishing a trust often falls under the scope of farm estate planning. Other methods of transfer consistent with farm business and estate planning include wills and gifts. Although it varies on a case-by-case basis, compared with a will, a trust is typically more complex and can sometimes be costlier to establish and manage. Given that trusts are typically more complex than wills, it would be expected that trusts would be used in situations involving larger amounts of land to be transferred. Indeed, the average transfer acreage for those planning to transfer their land through a trust over the 2015-19 period was 420 acres, compared with 47 acres for those planning to transfer land in a will.

Unlike a trust, in which ownership of the property is transferred when the trust is created, a will-based transfer takes place at the time of death of the landowner. Thus, while an estimated 57 million acres of farmland are eventually planned to be transferred through a will, based on the life expectancy of the owners, only about 20 percent of this land is expected to be transferred in the next 5 years. Gifting farmland is far more common among non-operators (22 percent of land expected to be transferred) than among operator landowners (8 percent of expected land transfers).

From Acquisition to Transfer – Is Land Involved in Sales Transactions Recycled?

As stated earlier, just over 2 percent of farmland is expected to be sold to a nonrelative in 2015-19, and it is a commonly held belief that farmland markets are relatively thin. This leads some to ask if the same land is repeatedly being put on the market. If the same parcels tend to be sold, it suggests that farmland available for purchase on the open market is drawn from a small subset of all farmland. If different parcels tend to be sold, it suggests that the supply of farmland that may be available for purchase is more variable over time. Of the 21 million acres of land expected to be sold in the next 5 years to a nonrelative, more than half (11 million acres) were originally obtained by a landowner who acquired a majority of his or her land through arm’s-length transactions. A majority of an additional 6.4 million acres set to be sold on the competitive market were inherited, while another 3.4 million acres were mainly purchased from family members.

Information on both land acquisitions and near-term transfer plans help paint a broad picture of the contemporary farmland market. Farmers generally have two options to acquire new land to begin or expand an existing operation: renting or purchasing. Based on TOTAL survey responses, a relatively small share of all U.S. farmland (2 percent) will be purchased through arm’s-length transactions in the next 5 years. Moreover, the majority of this land was itself originally purchased from a nonrelative of the current owner, suggesting that the supply of land available for purchase on the open market may not vary much over time. While the survey results present a picture of limited arm’s-length transactions, they also show that 6.4 million acres that will come on the market in 2015-19 was largely inherited. This finding, combined with the large share of farm transfers associated with trusts, suggests that the relatively small quantity of land expected to be transferred immediately through a market transaction likely represents a lower bound on the true amount of farmland that will be sold in the near future.

This article is drawn from:

- Bigelow, D., Borchers, A. & Hubbs, T. (2016). U.S. Farmland Ownership, Tenure, and Transfer. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. EIB-161.