Healthy Vegetables Undermined by the Company They Keep

- by Joanne Guthrie and Biing-Hwan Lin

- 5/5/2014

Highlights

- Vegetables—naturally low in calories and sodium and high in dietary fiber—are mostly eaten by Americans in prepared forms that alter their nutrient profile.

- Holding constant the total amount of food consumed, eating more vegetables in the forms currently favored by Americans would add calories and sodium.

- Reformulation of processed foods, improved labeling of packaged foods, and menu labeling of food prepared away from home may help Americans make more nutritious vegetable choices.

As the U.S. Government prepares to issue updated Dietary Guidelines for Americans in 2015, the question of how best to encourage Americans to eat a nutritious diet for a healthy weight is once again under discussion. Vitamin- and mineral-packed vegetables are naturally low-calorie, low-sodium, high-dietary-fiber foods, so it seems logical that eating more of them would be a good way to improve diets, reduce overall sodium intake, and control weight. Yet, research linking fruit and vegetable consumption to body weight has been inconclusive. Therefore, the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the U.S. Government’s consensus statement of nutrition policy, made only a qualified statement that fruits and vegetables may be a useful part of an overall approach to achieving and/or maintaining a healthy weight.

An analysis of American diets suggests that the answer is in the processing and preparation of our favorite vegetable-containing foods. Earlier ERS research found fruit consumption to be linked to healthier weight status, but for vegetable consumption there was no such link. The researchers speculated that the issue might be how the vegetables are prepared. Unlike naturally sweet fruit, American may find vegetables more palatable if prepared with added fats or oils, such as in fried potatoes or creamed spinach, or in a mixed dish like pizza.

More recently, ERS researchers returned to this question, examining in more detail the types of vegetables and vegetable-containing foods eaten by Americans. As hypothesized, they found that instead of eating vegetables in their simple, unadorned state, Americans often eat vegetables prepared in ways that add calories and sodium. They also tend to eat vegetables in forms that remove dietary fiber.

Eating More Fruit Found To Be Associated with Lower Weight—But Not Eating More Vegetables

In 2002, ERS researchers used data from USDA’s Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII) 1994-96 to investigate the relationship of fruit and vegetable consumption and weight status among children 5 to 18 years of age and adults. This survey collected data from a nationally representative sample of Americans on everything they ate and the amount consumed over 2 nonconsecutive days. Survey respondents were also asked to report their height and weight, and this information was used to compute their body mass index (BMI), a measure of overweight and obesity. Parents or guardians reported dietary and height and weight information for children less than 13 years of age.

The number of servings of fruits and vegetables each survey respondent consumed was calculated using the USDA’s Pyramid Servings Database. This database identifies the fruit and vegetable component of each food, whether a simple item like an apple or carrot sticks, or a combination food like a vegetable soup or a fruit pie, and converts it into the appropriate number of servings by food group. This allows all the forms in which fruits and vegetables are consumed—as solid, single items; as juices; or as part of combination foods—to be aggregated into a measure of the total number of servings consumed.

The researchers found that, on average, healthy weight children and adults ate more fruit than their overweight peers. After conducting a more complex analysis that controlled for personal characteristics that could affect weight, including age, gender, and race, they found consistent results. Higher fruit consumption was associated with lower BMI for adult men and women and for adolescent girls and boys 10 years of age and above.

Total vegetable consumption had no association with body weight. When vegetables were separated into two groups—white potatoes only, and all other vegetables—white potato intake was associated with higher BMI for both adult men and women. Intake of vegetables other than potatoes was associated with lower BMI among women but not among any other age-sex groups.

Researchers hypothesized that vegetables might not be as low-calorie as fruit because they are often eaten in ways that add calories. While 100 grams of a plain baked potato, eaten with skin contains 97 calories, 100 grams of French fries from a fast food restaurant typically contains 312 calories, according to USDA nutrient data. Other vegetables might also be frequently prepared in forms that add calories, explaining the lack of association with healthy weight.

Vegetables Are Frequently Eaten in Forms That Add Fat and Sodium

The hypothesis that Americans might be eating vegetables most often in forms that add calories and fat was explored in a second study by ERS researchers. Researchers used nationally representative dietary data from the 2003-04 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). NHANES interviewers collected dietary information using methods very similar to the CSFII. As before, participants reported everything they ate and the amount consumed over a 24-hour period, and the interview was repeated on a second, nonconsecutive day, providing 2 days of dietary intake data for each participant. USDA nutrient data were used to estimate the calorie and nutrient content of every food item consumed. The USDA MyPyramid Equivalents Database (MPED) 2.0 was constructed for use with the 2003-04 NHANES and used to identify the vegetable content of each food, such as soups, stews, juices, and sauces. At the time the study was conducted, a database to identify vegetable content of foods was not available for NHANES data newer than 2004. However, eating patterns observed in 2003-04 are likely to be similar to those today since food preferences and eating habits change slowly.

ERS researchers aggregated individual vegetable consumption from all sources—plain raw or cooked vegetables; vegetables from mixed dishes such as soups, stews and pastas; juices; sauces; etc.—and generated overall estimates of cups of vegetables consumed. Because Americans often make quite different choices when eating out, they examined vegetable consumption patterns for food prepared at home versus those for food prepared away from home. They separated foods by where prepared, so a sandwich made at home and taken to work for a brown-bag lunch would be considered a home-prepared food, whereas a pizza taken home from a restaurant would be considered as prepared away from home. They examined the effects of the types of vegetables consumed on intake of calories, sodium, and dietary fiber.

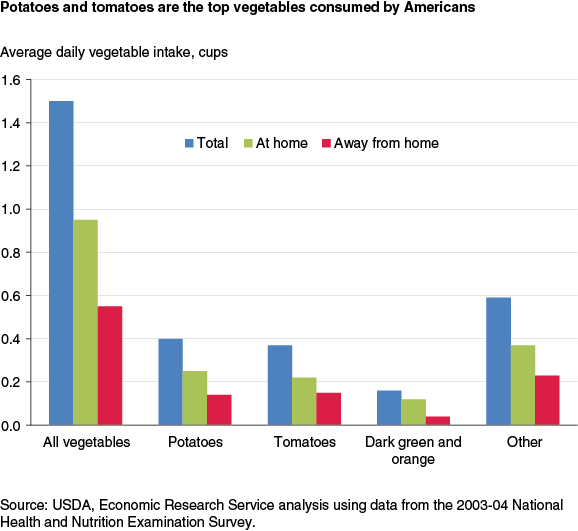

Researchers found that on average, Americans ate 1.5 cups of vegetables daily, about 50-60 percent of the 2-3 cups recommended for adults and older children. More than half of vegetable intake came from potatoes and tomatoes (51 percent), whereas only 10 percent came from dark green and orange vegetables. Some vegetables were eaten in their unadorned state—raw carrot sticks or sliced tomatoes—but most were consumed in prepared forms or as part of mixed dishes.

Potatoes, as had been hypothesized, were typically consumed in forms that added fat. At home, potato chips were the most commonly eaten form, whereas away from home, fried potatoes predominated. Other potato dishes, such as mashed and scalloped potatoes, are often prepared with added fats and sodium. Baked potatoes were popular, but most commonly—especially when eating out—the skin was not eaten, reducing dietary fiber content.

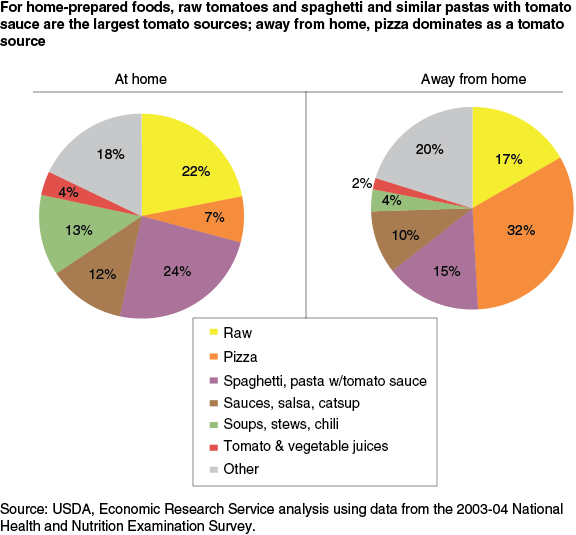

The predominance of fried potatoes was expected, but the results for tomatoes, the second-most consumed vegetable by Americans, may be more surprising. Although popular raw, most tomato is consumed as an ingredient in popular mixed foods, such as pastas and pizzas. To illustrate, when the researchers examined the leading sources of tomato consumed, they found that at home, raw tomato accounted for 22 percent of tomato consumption, while 24 percent came from tomato sauces for spaghetti and similar pastas. Among foods prepared away from home, pizza provided the largest share of tomato consumed, at 32 percent, followed by raw tomato at 17 percent, and spaghetti and similar pastas with tomato sauce at 15 percent.

The Dietary Guidelines recommend that Americans should lower their sodium intakes from the current average of approximately 3,400 mg daily to no more than 2,300 mg/day. Although tomatoes are naturally low in sodium, many of the tomato sauces featured in mixed dishes are high in sodium. While a cup of raw tomato has only 9 mg of sodium, according to the most recent USDA nutrient data canned tomato sauce typically contains more than 1,000 mg of sodium per cup.

Adding More American-Style Vegetables Can Increase Calories and Sodium

Having found that so much of Americans’ vegetable consumption is obtained in forms that add fat or sodium and reduce dietary fiber, ERS researchers analyzed the effect of adding more vegetables—in forms currently consumed by Americans—to the diet on calorie intake, sodium density (mg/1,000 kcal), and dietary fiber density (g/1,000 kcal). Researchers held the total amount of food consumed as measured in weight (grams) constant; as more vegetables were eaten, the amount of other foods consumed was lowered. For the analysis, they examined four categories of vegetables: potatoes, tomatoes, dark green and orange vegetables, and all other vegetables. Researchers estimated the effects of adding more vegetables and vegetable-containing foods to the diet using a method that controls for individual differences that may affect food intake such as age, gender, and personal tastes and preferences.

Contradicting what might have been expected from a shift to a higher vegetable diet, researchers found that calorie intake increased, with effects varying by type of vegetable and where the food was prepared. Eating an additional cup of potatoes in the forms prepared at home resulted in an increase of 88 calories, whereas eating an additional cup of potatoes prepared away from home increased calorie intake almost twice as much. This reflects the predominance of fried potatoes when eating out. For tomatoes, the difference in the calorie increase from foods prepared at home versus away from home was even larger. An additional cup of tomatoes from home foods increased calories by 59 versus a 364-calorie increase from away-from-home foods. This may be attributable to the popularity of calorie-laden combination foods like pizza as a tomato source. According to USDA’s MyPlate guidance, a piece of pepperoni pizza provides ¼ cup of vegetable, but also contains approximately 400 calories, making it a high-calorie source of vegetables.

Whether at home or away, increasing tomato consumption resulted in a more sodium-dense diet, likely reflecting the sodium content of tomato-sauce dishes that make up the bulk of tomato consumption. Eating more potatoes, whether at home or away, decreased sodium. Increasing dark green and orange vegetable intake of foods prepared at home by 1 cup reduced sodium density by 56 milligrams. But away-from-home foods containing dark green and orange vegetables had the opposite effect, increasing sodium by 186 milligrams per cup consumed. Both at home and away, raw carrots and greens are popular choices, but among the leading away-from-home choices are also dishes that include dark green and orange vegetables cooked with soy sauce, spinach dips, and other higher sodium items.

| Nutrient | Potatoes: at home | Potatoes: away | Tomatoes: at home | Tomatoes: away | Dark green and orange vegetables: at home | Dark green and orange vegetables: away | Other vegetables: at home | Other vegetables: away |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of increasing intake of each type of vegetable by 1 cup, holding total amount of food consumed constant | ||||||||

| Calories | 88 | 159 | 59 | 364 | 80 | NS | NS | NS |

| Sodium (mg) | -52 | -76 | 179 | 113 | -56 | 186 | 75 | 91 |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 0.30 | NS | 0.86 | NS | 1.38 | 1.07 | 1.14 | 0.49 |

| Effects on nutrient intake are attributable to consumption of vegetable-containing foods, including other non-vegetable ingredients. For example, potatoes may be fried with oil and have added salt; tomatoes may be consumed as a sauce on pasta or pizza. NS = not significant. Source: USDA, Economic Research Service analysis using data from the 2003-04 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. |

||||||||

Increasing Dark Green and Orange Vegetables Boosted Dietary Fiber

Dietary fiber is provided by nondigestable carbohydrates and related compounds in the foods we eat. Its bulk promotes a feeling of fullness, which may help control calorie intake, and it promotes healthy digestion. Vegetables, along with fruits and whole grains, are naturally rich sources of dietary fiber. However, fiber is often removed from vegetables by peeling, removing seeds, or extracting juice.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend 14 grams of dietary fiber per 1,000 calories consumed, which would be equivalent to about 28 grams per day for a 2,000 calorie diet. On average, Americans consume about 15 grams of dietary fiber daily, far less than recommended. The Dietary Guidelines state that these low intakes constitute a public health concern. Adding more potatoes and tomatoes from food prepared away from home would not significantly increase dietary fiber, probably because of losses during preparation or because individuals choose not to eat the skins on potatoes.

Eating more tomatoes and potatoes as prepared at home would boost dietary fiber, but not as much as increasing dark green and orange vegetables would. Consumption of an additional cup of dark green and orange vegetables as prepared at home would increase fiber by 1.38 grams, whereas an additional cup as prepared away from home would result in a 1.07-gram increase. Increased consumption of other vegetables was also associated with increased fiber intake, particularly the home-prepared versions, which added 1.14 grams of dietary fiber per cup.

Public-Private Efforts May Promote Healthier Vegetable Choices

When considering how increased vegetable consumption can support efforts to prevent obesity and reduce sodium intake, thinking about the typical forms in which Americans eat vegetables is important. Rather than simply eating more of their current favorite forms of vegetable-containing foods, Americans will need to add vegetables in forms that come with fewer added calories and sodium.

Combination foods such as pizzas and pastas may seem like a tasty and convenient way to add vegetables to the diet, and the vegetables in those foods do make nutritional contributions. For example, tomato sauce contains vitamins A and C and potassium. However, consumers need to be aware that along with the vegetable content of combination foods may come calories and sodium from the other parts of the dish. The presence of vegetables in a mixed food like heavily sauced pasta may lend a “health halo” to the dish in the minds of many consumers—that is, consumers may have an overly positive impression of the healthfulness of the dish based on considering only its healthy attributes. This may be most likely when eating out, since consumers may not know all the ingredients in an item. Calorie labeling will soon be required in American restaurant chains of 20 or more establishments. Such labeling may help consumers make healthier choices when eating out and create incentives for restaurants to offer more nutritious items.

Most sodium consumed by Americans is not added at the table from the salt shaker, but rather comes from processed items such as tomato sauce and canned soups. For this reason, the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans emphasized the importance of reducing the sodium content of packaged foods. Many food companies have made efforts to reduce the sodium content of their foods, encouraged by public-private efforts such as the National Salt Reduction Initiative. This initiative set voluntary goals for sodium reduction in packaged and restaurant foods. In 2013, the Initiative reported that 21 companies had made changes that met one or more of its goals. Nevertheless, changes are uneven. A recent report from the Center for Science in the Public Interest assessed changes in sodium content of 480 food products between 2005 and 2011. Of that group, sodium content had declined in 205 products, but it increased in 158. Sodium content of similar products varied considerably—for example one brand of tomato paste contained five times the amount of sodium as another brand. Unless consumers check the nutrition label and choose the lower sodium options, they may not consistently benefit from the improved products available.

Although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration permits front-of-label claims for low sodium products that could assist consumers to identify these products, some food companies may not choose to make these claims. They assert that consumers associate “low salt” claims with poor-tasting foods, making it difficult to successfully market lower sodium products. Instead, these food companies practice what has been called “stealth health,” reducing the sodium content of the item but not publicizing the change with front-of-label claims. A report from the Institute of Medicine stated that successfully marketing lower sodium products has been difficult for food companies. Consumers who are used to larger amounts of added salt may find it hard to accept lower salt versions of their favorite foods. New USDA school meal standards call for a gradual reduction in the sodium content of meals. This may help the younger generation grow up with more acceptance of a lower sodium diet.

This article is drawn from:

- “Impact on energy, sodium and dietary fibre intakes of vegetables prepared at home and away from home in the USA”. (2013). Public Health Nutrition, published online.

- Higher Fruit Consumption Linked With Lower Body Mass Index. (2002). USDA, Economic Research Service.