The Role of Conservation Program Design in Drought-Risk Adaptation

- by Steven Wallander, Daniel Hellerstein and Marcel Aillery

- 7/1/2013

Highlights

- Since USDA conservation programs are voluntary, farmers base their participation decisions on local conditions, among other factors, and those decisions are influenced by the level of local drought risk; this is a form of climate adaptation.

- Various aspects of conservation program design—including contract ranking, eligibility requirements, and participation constraints such as national and county enrollment caps—may limit how farmers are able to use these programs to adapt to drought risk; adjustments to any of these provisions will interact with underlying differences between farmers, including differences in exposure to drought risk.

- USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program provides a clear example of the interactions between existing climate adaptation and existing program provisions, which are generally designed to serve program goals that are unrelated to encouraging adaptation.

The 2012 U.S. drought invited historical comparisons. How did this drought compare with other large-scale droughts such as those in 1988, 1954-56, and, of course, the peak years of the dustbowl, 1934-36? For national-scale droughts, this sort of question is helpful in understanding drought severity, extent, and duration. Meteorologically, the 2012 drought was more extensive and more severe than both the 1988 and the 1954-56 drought. Asking similar historical questions at a smaller, regional scale reveals insights on the nature of drought—some regions experience severe or extreme drought more frequently than others.

When deciding what commodities to grow and how best to grow them, farmers generally consider a host of factors, but one of the most important is their growing conditions. Local climate conditions—such as average rainfall totals and average temperatures—influence farmer decisions, as does the risk that “normal” conditions will not prevail during the growing season. Drought is a prime example of a production risk resulting from abnormal weather conditions. Farmers in drought-prone regions may factor that risk into their farming decisions. Drought-risk adaptation involves farmers taking actions or making investments that reduce their vulnerability to drought. These actions and investments will generally be of greater benefit to farmers in areas that face a higher risk of drought during the growing season. As a result, other things being equal, it is expected that farmers in higher drought-risk regions will be more likely to take steps to reduce their vulnerability to drought before it occurs.

Many of the practices encouraged by USDA’s conservation programs—investment in irrigation efficiency improvements, adoption of conservation tillage, use of rotational grazing, and idling of sensitive lands—are frequently cited as ways to improve drought preparedness. Farmers facing a higher risk of drought, therefore, may favor these practices over other conservation practices. In other words, farmers can be engaging in drought-risk adaptation through participation in USDA’s conservation programs even though the programs are not explicitly designed to help farmers reduce their vulnerability to drought. To evaluate the extent to which drought-risk adaptation influences farmer behavior, ERS recently examined the role of drought risk in farmer participation in USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) and Environmental Quality Incentive Program (EQIP). This article presents some key findings of ERS’s assessment of the CRP, emphasizing the importance of conservation program design decisions to farmers interested in pursuing drought risk-adaptation through USDA programs.

Climate and Drought

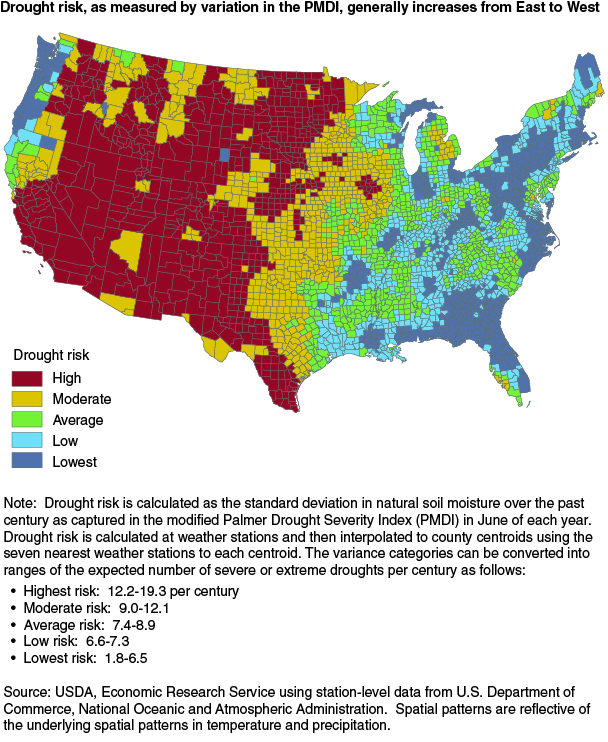

Drought risk is a measure of the tendency for a given location or region to experience severe or extreme drought. Meteorologists have established many measures of drought severity that reflect various aspects of water shortage. One of the most widely used measures of drought is the Palmer Modified Drought Index (PMDI), which focuses on soil moisture as it is accumulated or depleted over time. Because early to midsummer is a critical period for crop development for most major crops, this research uses the standard deviation in the local weather station’s PMDI in June of each year to measure a county’s drought risk. Due to how the PMDI is constructed, this drought-risk measure can be directly converted into the expected frequency of severe or extreme drought. In general, this measure follows the intuition that low-rainfall areas of the arid Western States are more drought prone than other areas, although drought risk is not the same as aridity.

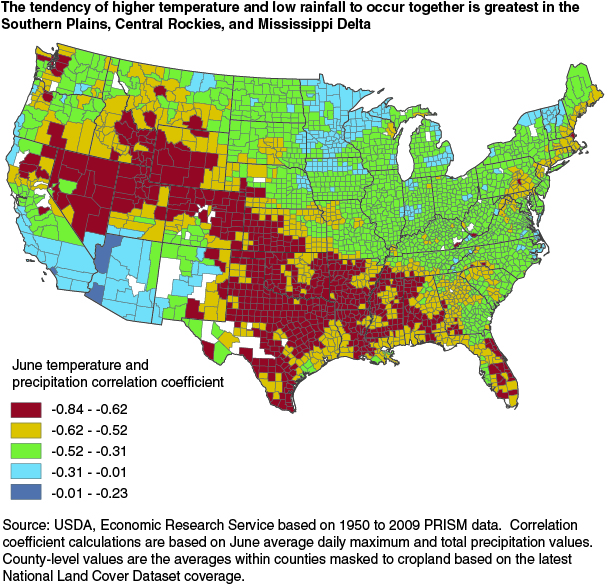

Since the PMDI is an index based on complex calculations from precipitation and temperature data, it can be helpful to examine the weather patterns that influence PMDI calculations. For example, some areas may be more drought prone because precipitation is more variable. Also, some areas are more likely to experience the combination of high temperatures and low precipitation at the same time. Based on an examination of 60 years of historical weather data for the month of June, the Southern Plains, Rocky Mountain, and Gulf Coast regions are more likely to experience below-average precipitation and above-average temperatures simultaneously than other regions. This combination is most likely to result in severe drought when average rainfall is not high to begin with, such as in the Southern Plains and Rocky Mountain regions.

It is projected that climate change may result in increased drought risk for many regions of the United States. If this occurs, more farmers will need to adapt to a heightened risk of drought, and as shown here, that is likely to involve increased interest among farmers in participating in USDA’s conservation programs.

CRP Participation and Drought

USDA’s CRP is a cropland retirement program that provides a range of environmental benefits by enrolling environmentally sensitive cropland in long-term (10- to 15-year) contracts to establish and maintain conservation covers. Producers receive an annual rental payment for acreage enrolled in the CRP as reimbursement for foregone crop sales. Enrollment of eligible land in the program occurs through voluntary signups, either during a periodic competitive general signup or through a continuous noncompetitive signup program restricted to high-priority land-use practices—such as filter strips to protect waterways. As of March 2013, about 27 million acres were enrolled in the CRP, with about 80 percent of those acres enrolled through a general signup.

Enrollment in the CRP may have several added benefits for producers in drought-prone regions. First, producers in these regions may prefer the constant stream of CRP rental payments to the potential volatility of crop revenue. Second, CRP land may help replenish groundwater and, thus, provide a benefit to surrounding irrigated cropland. Lastly, the CRP includes provisions for emergency haying and grazing in the instance of severe or extreme drought, a provision more likely to be used by farmers in higher risk regions where livestock production may be more predominant.

To evaluate the impact of drought risk on CRP participation, ERS examined data on enrollment offers made in CRP general signups between 1997 and 2011. CRP enrollment eligibility is limited to an estimated 212 million acres, about 23 percent of farmland nationwide. In addition, enrollment in each signup is determined through a competitive process in which offers are ranked according to an Environmental Benefits Index (EBI) that reflects the environmental benefits and cost of each offer. Finally, in most counties, no more than 25 percent of the county’s cropland may be enrolled in the CRP. Combined, these elements of program design limit the extent to which producers may be able to adapt to drought risk by enrolling in the CRP.

Nonetheless, when controlling for other factors that influence participation, such as EBI scores, soil rental rates, and county enrollment caps, drought risk is found to have a large impact on the likelihood that land will be offered for enrollment in the CRP. A 1-percent increase in drought risk, on average, is associated with a 2.4-percent increase in the number of acres offered for enrollment in the CRP. This adaptation to drought risk by farmers potentially interacts with program provisions in ways that may be of interest to policymakers. First, the provisions are in place to balance existing program goals, and if policymakers consider changing those provisions for reasons unrelated to climate and drought risk, it is important to know how different regions will respond to those changes. Second, there are suggestions that “facilitating climate adaptation” should be added to the goals served by conservation programs, which means that policymakers may wish to explicitly reconsider these program provisions in light of farmers’ adaptation responses.

To demonstrate how the design of the existing program may limit this adaptation, ERS used a simulation model to predict farmer response to a number of hypothetical changes in CRP’s eligibility and selection criteria. Since the program is completely voluntary but may involve application preparation costs, farmer interest in the program is expected to increase as the chance of having an offer accepted increases. Therefore, design changes that favor farmers in drought-prone regions should elicit an increase in the number of acres they offer for enrollment if the existing program design is discouraging some farmers from participating.

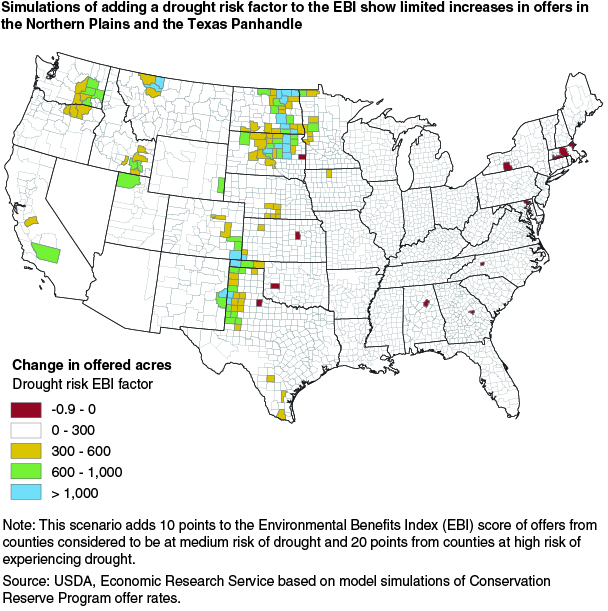

The first scenario examined shows the effect of explicitly recognizing drought-risk adaptation in CRP’s offer selections by adjusting the EBI ranking criteria while holding program eligibility criteria constant. Adding EBI points for drought risk implicitly creates a tradeoff between drought risk and the existing environmental benefits covered by other components of the EBI. Mapping these tradeoffs is beyond the scope of this study, as doing so would require a more complex behavioral model to capture how farmers would change their overall EBIs and how that would change which offers are accepted by USDA's Farm Service Agency. The EBI currently ranks offers based on their environmental benefits—such as water quality, wildlife habitat, and soil erosion—and program costs, but it does not consider an area’s drought risk. A scenario is envisioned in which farms in more drought-prone counties would receive an added 10 to 20 EBI points on their CRP offers, which amounts to a 5- to 20-percent increase in their total EBI score, depending on the county. Spatially, the resulting increase in offers is most evident in bands of counties in the eastern portion of the Northern Plains and the western part of the Southern Plains.

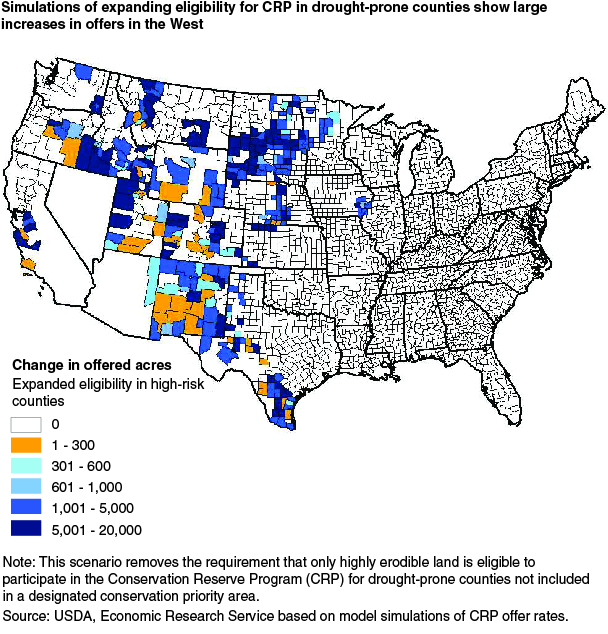

In contrast, a second scenario retains the existing EBI ranking but expands program eligibility in drought-prone counties to include land that is not considered highly erodible. This scenario would treat drought-prone counties the same way the existing program treats conservation priority areas. That is, all land in drought-prone areas that satisfies CRP’s cropping history requirements would be eligible to participate in the program, but winning bids would still need to score highly based on the environmental benefits they are expected to provide. Under this scenario, the Mountain West and the Western Plain regions experience the largest increases in offers. This largely reflects the fact that many of these counties have offer rates that are currently constrained by eligibility rules that limit participation to land that is considered highly erodible or land that is in conservation priority areas.

A third scenario (not shown) would expand program eligibility by raising the cap currently placed on the share of a county’s cropland that can be enrolled in the CRP. Significantly raising the current 25-percent enrollment cap would result in more land being offered for CRP enrollment, with offers in drought-prone areas increasing the most, on average, even if the higher enrollment cap was applied nationwide. This suggests that the current 25-percent enrollment cap discourages some farmers from making offers to the program and may be particularly binding in drought-prone areas.

Together, these scenarios demonstrate how climate adaptation through the CRP can be limited by various aspects of current program design. Such limitations may be necessary for the program to effectively address its mandate, but awareness of the interactions with climate adaptation may help farmers, environmentalists, and policy officials as they prepare climate adaptation plans. This research (including ERS research on EQIP in the source report to this article) also demonstrates, more generally, that adaptive decisions by farmers will affect conservation program outcomes even if those programs do not explicitly take such behavior into account.

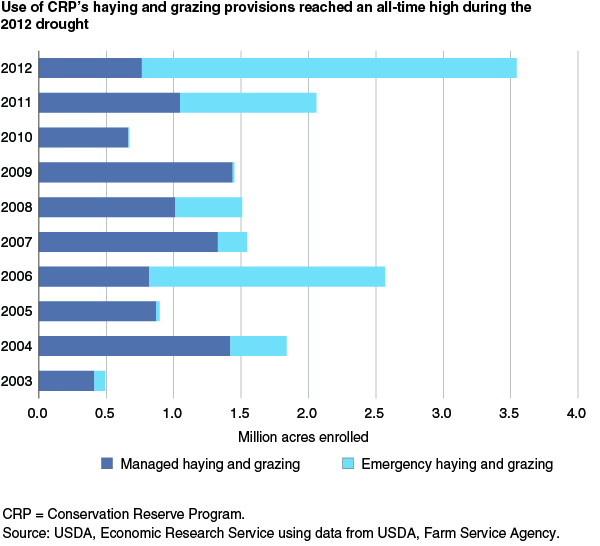

This research has focused on longrun patterns in conservation program participation. However, the impact of conservation programs on participating farms experiencing drought can vary dramatically from year to year. This is particularly evident in farmer response to CRP’s haying and grazing provisions during the 2012 drought. Under these provisions, enrollees can capture forage benefits on enrolled acreage, consistent with an approved conservation plan, if they are in counties in declared drought disaster areas and are willing to accept a reduction in their annual CRP rental payments. During the 2012 drought, these provisions were used on more than 2.8 million acres, far more than in any other year.

Conclusions

The interaction between drought risk and CRP participation demonstrates three aspects of climate change adaptation. First, climate change adaptation may involve elements of climate, such as drought risk, that are not revealed by changes in average temperature and precipitation. While extreme weather events such as droughts are difficult to predict, if farmers perceive changes in the risks they face, they are likely to search for ways to reduce their vulnerabilities. Second, climate change adaptation will impact USDA programs that are not necessarily designed with such adaptation in mind. To the extent that programs support farming practices that reduce vulnerabilities to climate change risks, program participation will be affected as those risks change. Lastly, due to the complexities of program design, there are important interactions between drought risk adaptation and various program provisions. Using CRP as an example, this article demonstrates how various changes to these provisions may lead to greater drought-risk adaptation, which may or may not be the intended consequence of these changes. Simulations demonstrate the interaction between farmer behavior and program provisions. The potential for tradeoffs between climate adaptation and environmental benefits for conservation programs is related to this interaction but is beyond the scope of this research.

Based on ERS research results, drought risk influences program participation to the extent that program designs allow. By providing adaptation opportunities to farmers, USDA’s conservation programs have helped farmers address, to some extent, drought preparedness while satisfying the programs’ primary conservation goals. While conservation programs could be changed to allow more significant use in drought adaptation in the future, doing so would have implications for regional enrollment distribution, environmental benefits, and program cost effectiveness.

This article is drawn from:

- Wallander, S., Aillery, M., Hellerstein, D. & Hand, M.S. (2013). The Role of Conservation Programs in Drought Risk Adaptation. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. ERR-148.

We’d welcome your feedback!

Would you be willing to answer a few quick questions about your experience?