ERS Charts of Note

Subscribe to get highlights from our current and past research, Monday through Friday, or see our privacy policy.

Get the latest charts via email, or on our mobile app for  and

and

Friday, January 26, 2018

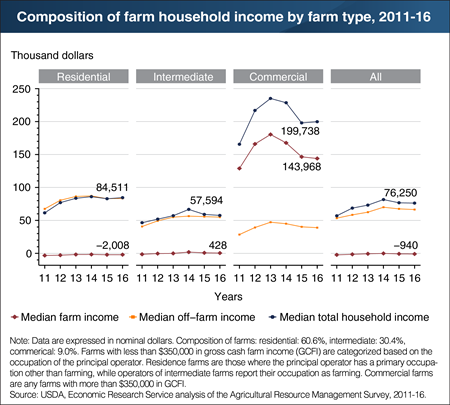

Most farm households rely on off-farm income, such as wages from a job outside the farm. Typically, only commercial farm households receive a substantial share of their income from the farm. For example, in 2016, the median farm income was negative $2,008 for households operating residence farms (where the operator primarily works off-farm or is retired from farming), while median off-farm income was $83,400. Households operating intermediate farms (smaller farms where the operator’s occupation is farming) also earn the bulk of their income from off-farm sources. In contrast, households operating commercial farms—where gross cash income is $350,000 or more—derive most of their income from the farm (nearly $144,000 in 2016). Changes to their total household income follow profits from farming. Most agricultural production takes place on commercial farms. In 2016, residential and intermediate farms together accounted for over 90 percent of U.S. family farms and one-quarter of the value of production. By comparison, commercial farms accounted for 9 percent of family farms and three-quarters of production. This chart is based on data from the ERS data product Farm Household Income and Characteristics, updated November 2017.

Wednesday, November 29, 2017

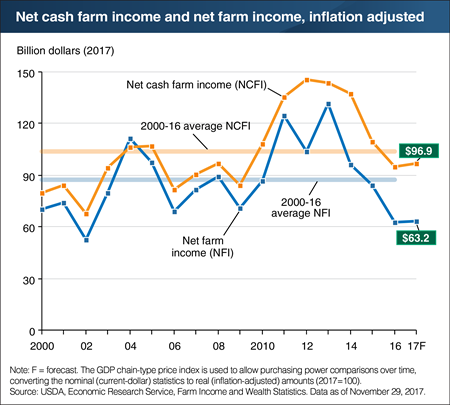

After several years of decline, net farm income in 2017 for the U.S. farm sector as a whole is forecast to be relatively unchanged at $63.2 billion in inflation-adjusted terms (up about $0.5 billion, or 0.8 percent), while inflation-adjusted U.S. net cash farm income is forecast to rise almost $2.0 billion (2.1 percent) to $96.9 billion. Both profitability measures remain below their 2000-16 averages, which included substantial increases in crop and animal/animal product cash receipts from 2010 to 2013. Net cash farm income and net farm income are two conventional measures of farm sector profitability. Net cash farm income measures cash receipts from farming as well as cash farm-related income, including government payments, minus cash expenses. Net farm income is a more comprehensive measure that incorporates noncash items, including changes in inventories, economic depreciation, and gross imputed rental income. Find additional information and analysis on ERS’s Farm Sector Income and Finances topic page, released November 29, 2017.

Wednesday, August 30, 2017

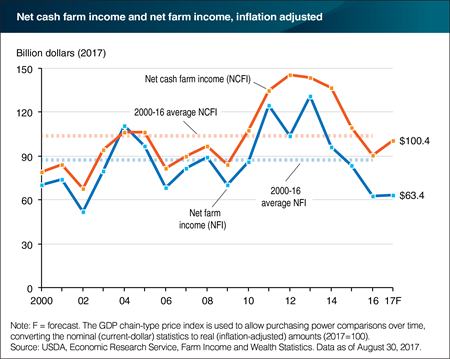

After several years of declines, inflation-adjusted U.S. net farm income is forecast to increase about $0.9 billion (1.5 percent) to $63.4 billion in 2017, while inflation-adjusted U.S. net cash farm income is forecast to rise almost $9.8 billion (10.8 percent) to $100.4 billion. The expected increases are led by rising production and prices in the animal and animal product sector compared to 2016, while crops are expected to be flat. The stronger forecast growth in net cash farm income, relative to net farm income, is largely due to an additional $9.7 billion in cash receipts from the sale of crop inventories. The net cash farm income measure counts those sales as part of current-year income, while the net farm income measure counts the value of those inventories as part of prior-year income (when the crops were produced). Despite the forecast increases over 2016 levels, both profitability measures remain below their 2000-16 averages, which included surging crop and animal/animal product cash receipts from 2010 to 2013. Net cash farm income and net farm income are two conventional measures of farm sector profitability. Net cash farm income measures cash receipts from farming as well as farm-related income including government payments, minus cash expenses. Net farm income is a more comprehensive measure that incorporates non-cash items, including changes in inventories, economic depreciation, and gross imputed rental income. Find additional information and analysis on ERS’s Farm Sector Income and Finances topic page, released August 30, 2017.

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

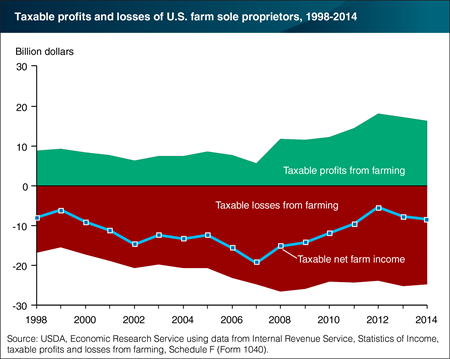

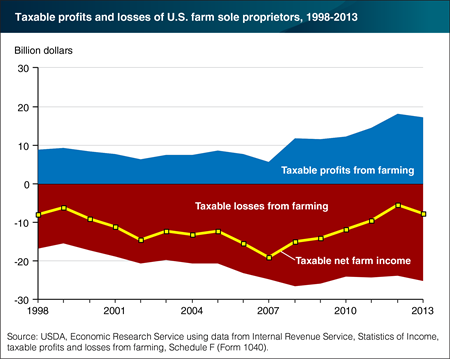

Nearly 90 percent of family farms are structured as sole proprietorships. These entities are not subject to pay income tax themselves; rather, the owners of the entities (farmers) are taxed individually on their share of income. Numerous Federal income tax law provisions allow farmers to reduce their tax liabilities by reporting losses. From 1998 to 2008, for example, taxable losses from farming (the red area of the chart) rose from $16.7 billion to $24.6 billion. This was due, in part, to changes in the tax code beginning in 2001 that expanded the ability of farms to deduct capital costs—such as tractors and machinery—in the year the equipment was purchased and used. Between 2007 and 2014, strong commodity prices bolstered farm-sector profits (the green area), but taxable net farm income (the blue line) remained negative. Farm sole proprietors, in aggregate, have reported negative net farm income since 1980; in other words, they’ve reported a farm loss due to higher farm expenses than income. In 2014, the latest year for which complete tax data are available, U.S. Internal Revenue Service data showed that nearly 67 percent of farm sole proprietors reported a farm loss. This chart appears in the ERS topic page for Federal Tax Policy Issues, updated January 2017.

Friday, March 24, 2017

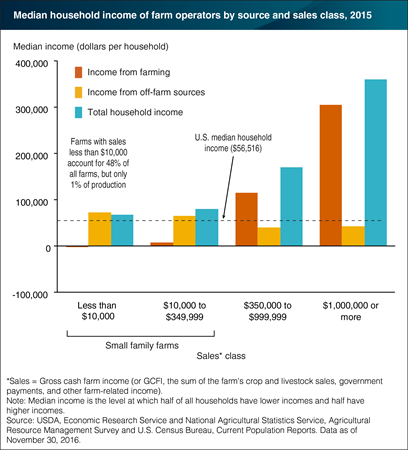

In 2015, farm households had a median total income of $76,735 per household—a third greater than that of all U.S. households ($56,516). Median total household income increased with farm size, with the median income of households operating small family farms approximating the U.S. median household and those operating larger family farms far exceeding it. The source of household income also varied with farm size: As farm size decreased, off-farm income represented a larger share of total household income. Households operating midsize and large farms (gross cash farm income or GCFI greater than $350,000) earned the majority of their total household income from their farm operations. By comparison, more than half of households operating small farms (GCFI less than $350,000) incurred small losses from farming, so the majority of their total household income came from off-farm sources. Wages from off-farm jobs accounted for more than half of off-farm income across all farm households. Farm households also receive significant income from transfers (such as Social Security or private pensions), interest and dividends, and non-farm business income. This chart appears in the ERS data product Ag and Food Statistics: Charting the Essentials, updated March 2017.

Thursday, March 9, 2017

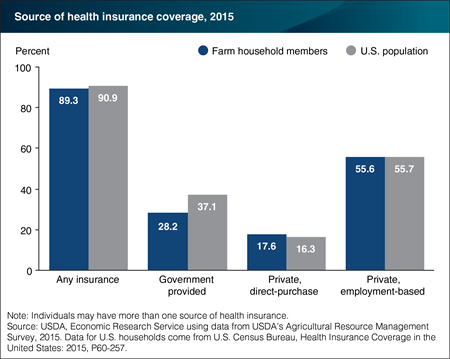

Health insurance can help people and households manage the cost and uncertainty of healthcare expenses. Most Americans with health insurance coverage receive it through their employers, and farm households are no exception. Although many farm operators are self-employed, in the majority of farm households either the operator or spouse is employed off-farm. In 2015, more than half of farm household members had health insurance coverage through an employer—close to the rate for the overall U.S. population. Farmers reported similar rates to the general population in purchasing their health insurance directly from an insurance company—and are less likely to receive health insurance from a government-provided program, such as Medicare or Medicaid. Over 89 percent of farmers had some form of health insurance, similar to the general population (nearly 91 percent). This chart appears in the topic page for Health Insurance Coverage, updated December 2016.

Monday, February 27, 2017

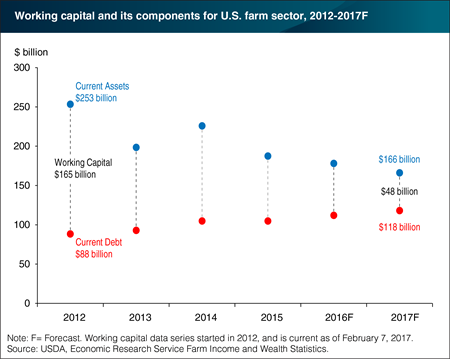

Farm financial liquidity describes how easily the U.S. farm sector can convert assets to cash in order to meet its short-term debt obligations. One measure of liquidity is working capital, the difference between current assets (such as cash and inventory) and short-term debt. Higher working capital means better financial health for the farm sector. ERS expects that working capital for the farm sector could contract to $48 billion by the end of 2017. The erosion in working capital was caused both by the reduction in the value of current assets (down $87 billion since 2012) and growing current debt (up $30 billion since 2012). Although working capital has weakened since ERS started tracking this measure in 2012, this decline followed record highs in net cash farm income from 2011 to 2013. The balance sheet forecast also indicates that farm solvency ratios—which measure whether debt can be met in a timely manner—are favorable compared to 25-year historical averages. However, farm solvency has weakened for 5 consecutive years; taken together with the decline in working capital, this pattern reflects a modest increase in farm financial risk exposure for the sector as a whole. This chart is based on the ERS Farm Income and Wealth Statistics data product, updated February 7, 2017.

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

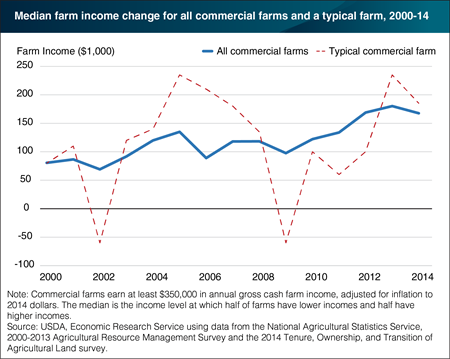

Commercial farm income is highly variable from year to year, fluctuating with output and prices. Income variability can affect key farm decisions, including how much to invest in farm assets (such as land or machinery) and how much to save as a cushion for low-earning years. Aggregate statistics, like the median income for all farms, can provide useful insight into how the farm sector as a whole fares from year to year—but can mask considerable variation for individual farms. For example, farms in one region might be thriving, whereas in another region they might be experiencing low incomes due to a localized drought. Between 2000 and 2014, median farm income for commercial farms ranged from about $70,000 to $180,000, with income fluctuating between consecutive years an average of $20,000. By comparison, a typical (representative) commercial farm with the same average income as the median commercial farm (about $120,000) could see its income fluctuate much more—with an average income swing of $86,000. This chart appears in the ERS report “Farm Household Income Volatility: An Analysis Using Panel Data From a National Survey,” released February 2017.

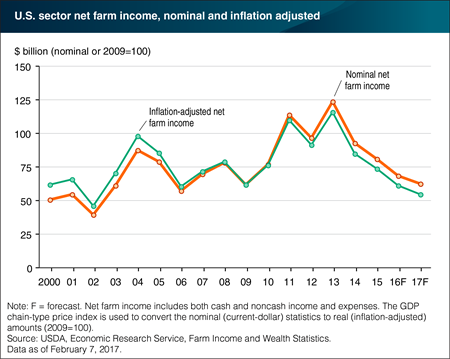

Tuesday, February 7, 2017

Net farm income is a conventional measure of farm sector profitability that is used as part of the U.S. Gross Domestic Product calculation. Following several years of record highs, net farm income trended downward from 2013 to 2016. For 2017, ERS forecasts net farm income will fall to $62.3 billion ($54.8 billion in inflation-adjusted terms). If realized, this would be an 8.7 percent decline from the prior year and a decline of 49.6 percent from the record high in 2013. The expected decline in 2017 net farm income is driven by a forecast reduction in the value of production. Crop value of production is forecast down $9.2 billion (4.9 percent), while the value of production of animal/animal products is forecast to decline by less than $1 billion (0.5 percent). Find additional information and analysis in ERS’ Farm Sector Income and Finances topic page, released February 7, 2017.

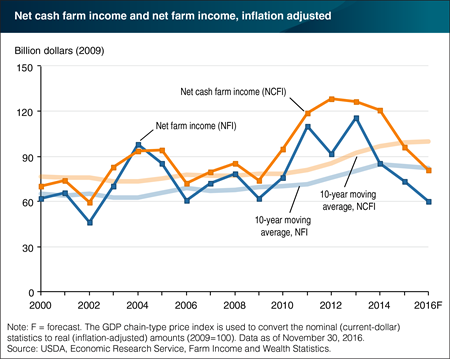

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

Net cash farm income and net farm income are two conventionally used and related measures of farm sector profitability. The first measure includes cash receipts, government payments, and other farm-related cash income net of cash expenses, while the second is more comprehensive and incorporates noncash transactions such as implicit rents, changes in inventories, and economic depreciation. Following several years of high income, both measures have trended downward since 2013. ERS forecasts that net cash farm and net farm income for 2016 will be $90.1 billion and $66.9 billion, respectively, or $80.9 billion and $60.1 billion, respectively, when adjusted for inflation (in 2009 dollars). Cash receipts declined across a broad set of agricultural commodities in 2015, and are expected to fall further in 2016—primarily for animal/animal products. Production expenses are forecast to contract in 2016, but not enough to offset the commodity price declines. Net cash farm and net farm income are below their 10-year averages, which include surging crop and animal/animal product cash receipts from 2010 to 2013. Find additional information and analysis in ERS’ Farm Sector Income and Finances topic page, updated November 30, 2016.

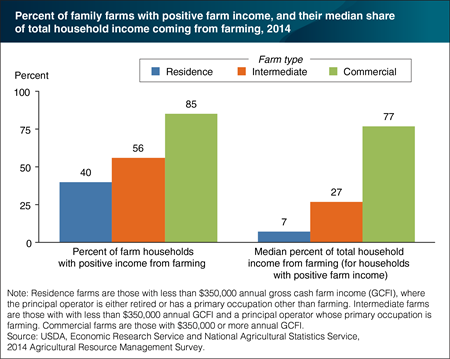

Thursday, August 4, 2016

The roughly 2.05 million U.S. family farms vary widely in size and by the share of household income from farming. Farm income contributes little to the annual income of farm households operating residence farms—those with annual gross cash farm income (GCFI) less than $350,000 and where the principal operator is either retired or has a primary occupation other than farming. In contrast, farm income is a secondary source of income for households with intermediate farms—those with annual GCFI less than $350,000 and a principal operator whose primary occupation is farming. For commercial farms with annual GCFI greater than $350,000, farm income is a primary source of income. In 2014, 40 percent of residence farms had positive income from farming activities, which contributed only 7 percent to total household income for the typical (or median) household reporting positive farm income. For households of intermediate farms, 56 percent had positive farm income, which comprised 27 percent of their total household income. Most commercial farms—85 percent—had positive farm income, and farm income typically accounted for 77 percent of total income for these households. Annual income from farming is volatile—15 percent of households of commercial farms experienced a loss from their farming operation in 2014. This chart is found in the ERS topic page on Farm Household Well-being.

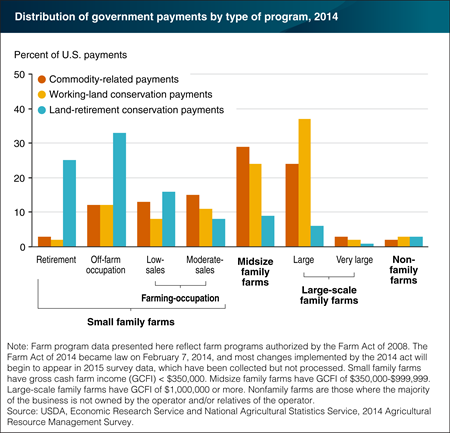

Tuesday, July 12, 2016

Farmers can receive government farm program payments from three broad categories of agricultural programs: commodity-related programs, working-land conservation programs, and land-retirement conservation programs. The distribution of payments in each category varies by farm type. In 2014, nearly 70 percent of commodity-related program payments went to moderate-sales, midsize, and large family farms, roughly proportional to their 80-percent share of acres in program-eligible crops. Midsize and large family farms together received about 60 percent of working-land payments that help farmers adopt conservation practices on agricultural land in production. Land-retirement programs pay farmers to remove environmentally sensitive land from production. Retirement, off-farm occupation, and low-sales farms received about three-fourths of these payments. Retired farmers and older farmers on low-sales farms may be more likely to take land out of production as they scale back their operations. Although government farm program payments can be important to the farms receiving them, 75 percent of farms in 2014 received no government payments. (These data summarize payments made in 2014. The Farm Act that was passed in 2014 introduced changes to commodity programs as part of a shift to greater reliance on crop insurance; most of those changes will be reflected in the source data beginning in 2015. Nevertheless, who receives particular government payments will continue to reflect farm and operator characteristics.) This chart is found in the ERS report America’s Diverse Family Farms: 2015 Edition.

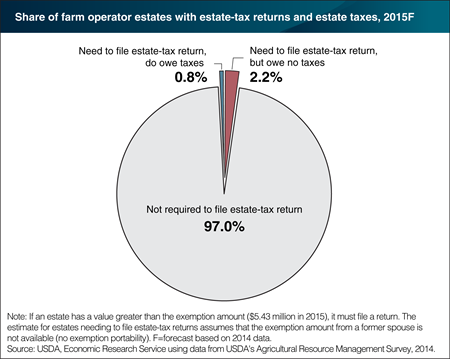

Monday, June 20, 2016

The Federal estate tax applies to the transfer of property at death. Under present law, the estate of a decedent who, at death, owns assets in excess of the estate-tax exemption amount ($5.43 million in 2015) must file a Federal estate-tax return. However, only those returns that have a taxable estate above the exempt amount (after deductions for expenses, debts, and bequests to a surviving spouse or charity) are subject to tax at a graduated rate, up to a current maximum of 40 percent. Based on simulations using farm-level survey data from USDA’s 2014 Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS), about 3 percent of farm estates would have been required to file an estate tax return in 2015, while 0.8 percent of all farm estates would have owed any Federal estate tax. This chart is based on the ERS topic page on Federal Estate Taxes.

Thursday, April 14, 2016

U.S. farm households generally receive income from both farm and off-farm activities, and for many, off-farm income largely determines the household’s income-tax liability. Since 1980, farm sole proprietors, in aggregate, have reported negative net farm income for tax purposes. From 1998 to 2008, both the share of farm sole proprietors reporting losses and the total amount of losses reported generally increased, due in part to deduction allowances for capital expenses. Since 2007, strong commodity prices bolstered farm-sector profits and the net losses from farming declined, leading to a peak in taxable profits (though still a negative taxable amount on net) in 2012. In 2013, the latest year for which complete tax data are available, U.S. Internal Revenue Service data showed that nearly 68 percent of farm sole proprietors reported a farm loss, totaling $25 billion. The remaining farms reported profits totaling $17 billion. This chart is found on the ERS Federal Tax Issues topic page, updated April 2016.

Wednesday, February 24, 2016

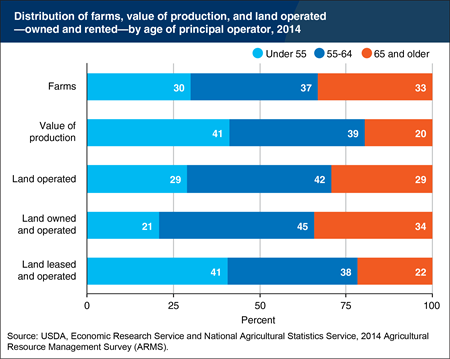

The average age of principal operators in the latest Census of Agriculture (2012) was 58 and has been greater than 50 since the 1959 Census. That farmers are older, on average, than other self-employed workers is understandable, given that the farm is the home for most farmers, and they can gradually phase out of farming over a decade or more. While older (age 65+) farmers make up a third of all farm operators, they account for a much smaller share (20 percent) of production. Nevertheless, older farmers still operate on 29 percent of all U.S. farmland (on land owned or leased, slightly less than their share of all farms). The largest portion of owned farmland is held by producers age 55-64; operators over 55 tend to own the land they farm, while younger operators are more likely to lease it. Older farmers’ land will shift to existing or new farms—or go into nonagricultural uses—as they exit agriculture. This chart is based on the information found in the Farm Structure and Organization topic page.

Friday, February 19, 2016

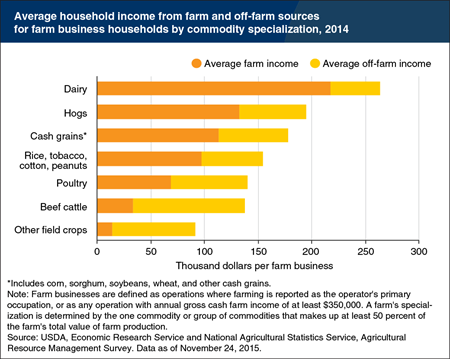

On average, households associated with farm businesses supplement farm income with income from off-farm sources. However, across different types of farm operations, the extent that off-farm income supplements farm income varies considerably. For example, with its extensive and ongoing time demands, managing a dairy farm rarely permits an operator to work many hours off-farm and is a main reason why farm income constitutes over four-fifths of these households’ total income. In 2014, households with farm businesses specializing in dairy and hogs had the highest average total household income (combining income from farm and off-farm sources), and the highest shares of household income derived from farming, followed by farms specializing in cash grains (corn, soybeans, sorghum, or wheat). Farm households with businesses specializing in beef cattle, other field crops, and poultry had the largest shares of average household income derived from off-farm activities. This chart is a variation of one found in the Farm Household Well-being topic page, and based on data available in ARMS Farm Financial and Crop Production Practices.

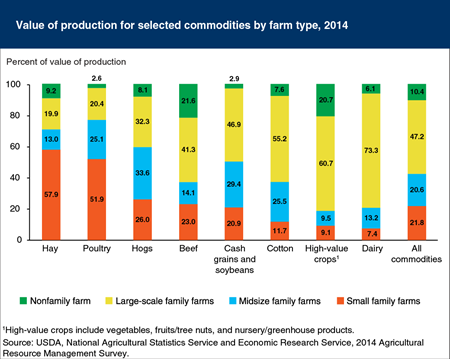

Friday, January 8, 2016

In 2014, 99 percent of U.S. farms were family farms, where the principal operator and his or her relatives owned the majority of the business. Most of U.S. farm production—68 percent—occurred on the 9 percent of farms classified as midsize or large-scale family farms having at least $350,000 in annual gross cash farm income (GCFI). Those farms together accounted for most production of dairy (87 percent of production), cotton (81 percent), and cash grains/soybeans (76 percent). Large-scale family farms alone (those with annual GCFI of $1 million or more) produced 73 percent of dairy output in 2014. Although small family farms (with less than $350,000 annual GCFI) accounted for 90 percent of U.S. farms, they contributed just 22 percent to U.S. farm production. Among some commodity specializations, though, small family farms account for a much higher share of production, accounting for over half of poultry output (mostly under production contracts) and hay. Non-family farms accounted for 10.4 percent of all production, but were most prominent in high-value crops and beef (through operating feedlots). This chart is found in America’s Diverse Family Farms: 2015 Edition, released in December 2015.

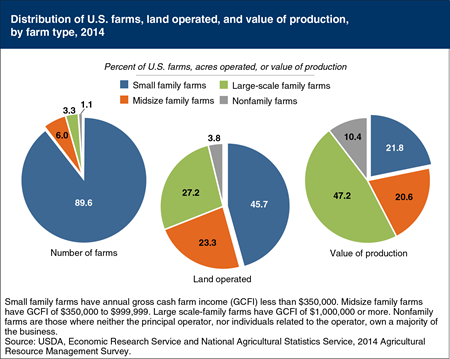

Thursday, December 10, 2015

In 2014, 99 percent of U.S. farms were family farms, where the principal operator and his or her relatives owned the majority of the business. Most were small family farms, having less than $350,000 in annual gross cash farm income (GCFI)—which includes commodity cash receipts, other farm-related income (such as receipts from custom work or production contract fees), and government payments. In 2014, these small family farms accounted for 90 percent of all U.S. farms, 46 percent of the land operated by farms, and 22 percent of agricultural production. Large-scale family farms—with $1 million or more in annual GCFI—accounted for about 3 percent of all farms, but had a disproportionately large share of the value of production (47 percent). This chart is found in America’s Diverse Family Farms: 2015 Edition, released December 2015.

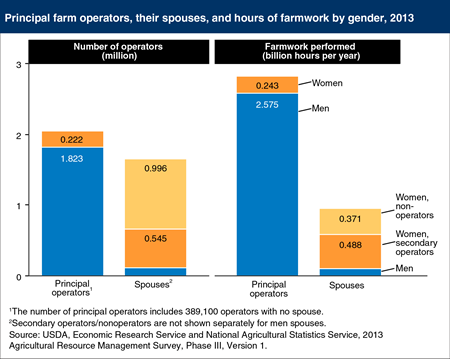

Wednesday, October 7, 2015

About 222,000 women are principal farm operators, or the person most responsible for making day-to-day decisions about the farm; 1.5 million women are spouses of principal operators. About one-third of these women spouses are secondary operators who work on the farm and participate in day-to-day decisions with their husband. The remaining women spouses do not make management decisions and are not farm operators. There are nearly one million of these nonoperator spouses, 46 percent of whom provide farm labor and collectively work 371 million hours on farms. Their labor amounts to 10 percent of the total hours worked on farms by principal operators and their spouses, and 34 percent of the total hours worked by female principal operators and spouses. The average hours of farm work—for persons reporting work hours—is substantial for women principal operators (1,097 hours per person per year), secondary operator spouses (895 hours/person/year), and nonoperator spouses (818 hours/person/year). Nonoperator women spouses contribute significant time to farm operations. This chart is an extension and update of information presented in the ERS report, Characteristics of Women Farm Operators and Their Farms, EIB-111, April 2013.

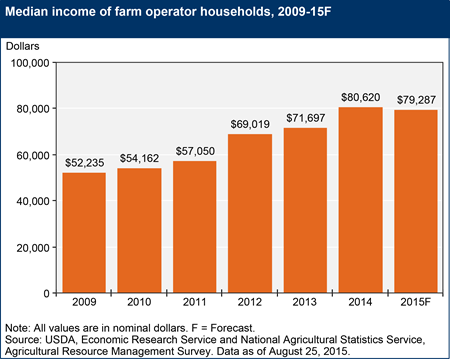

Tuesday, September 8, 2015

The median total income of farm households has increased steadily over the past 5 years (in both nominal and inflation-adjusted terms), peaking at an estimated $80,620 in 2014. However, it is forecast to decrease slightly in 2015, to $79,287. Households with commercial farms—operations which earn at least $350,000 in gross cash farm income—derive roughly three-fourths of their income from farming. Conversely, off-farm income contributes substantially to the total income of many farm households, especially those with smaller farms or a primary occupation other than farming. Farm households, on average, derive roughly 60 percent of their off-farm income from wages, salaries, and operating other businesses, while the remaining portion comes mostly from interest, dividends, and private and public transfer payments. Farm household median income remains higher than the median income of U.S. households, which was $51,939 in 2013 (the latest figure available). This chart is based on the Farm Household Well-Being Topic Page.