Specialized Stores Serving WIC Customers in California Improve Food Access Without Raising Food Costs

In fiscal year 2018, USDA’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) served 6.9 million people: low-income, nutritionally-at-risk pregnant, breastfeeding, and postpartum women and their infants and children up to age 5. WIC participants receive a benefit package redeemable for specific nutritionally tailored food products, typically at commercial food retailers. WIC State agencies charged with administering the program have significant latitude in deciding to authorize retailers, which may have implications for food costs and participants’ food access.

Nationally, the majority of stores that redeem WIC benefits are typical food retailers such as supermarkets, medium-sized grocery stores, and smaller convenience stores. States also have the option of authorizing “above-50-percent” (A50) stores that derive more than 50 percent of their food sales from WIC transactions. A50 stores typically cater almost exclusively to WIC customers by stocking primarily the foods that can be purchased with WIC benefits and by employing cashiers knowledgeable about WIC transactions. A50 stores tend to locate close to WIC clinics, which in turn are located close to WIC participants, thereby increasing participants’ geographic access to WIC-provided foods. Federal regulations forbid A50 stores’ prices from exceeding a State’s average WIC prices. In 2012, 13 State agencies authorized around 1,300 A50 stores to accept WIC benefits.

In California, the largest State WIC program, A50 stores play a significant role in the program, redeeming one-third of the value of the State’s WIC benefits in 2012. ERS staff and colleagues at University of California at Davis estimated A50 stores’ impact on food costs and participant access using data on WIC transactions that took place in the Greater Los Angeles area between October 2009 and February 2012. The researchers simulated participant shopping behavior under a hypothetical scenario where no A50 stores existed in California. Instead, WIC transactions in A50 stores were “re-shopped” to another WIC-approved store frequented by the A50 shopper or, if there was no such store, another nearby WIC-approved store popular with WIC participants.

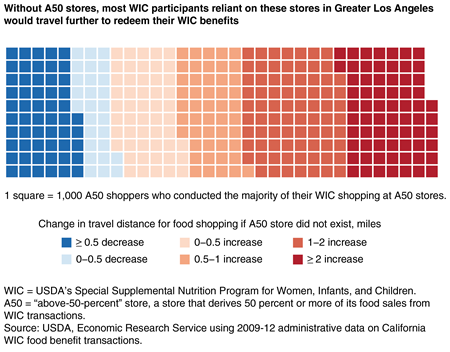

This “re-shopping” resulted in most A50 patrons having to travel a greater distance for their food shopping. For instance, for 44 percent of the participants who conducted the majority of their WIC shopping at A50 stores, simulated travel distances between the new shopping location and the local WIC clinic (a proxy for participants’ home locations) increased by 1 mile or more compared to distances from the actual shopping location. For 21 percent of these A50 shoppers, travel distances increased by 2 miles or more.

A50 stores also appeared to produce modest food cost savings, as the absence of these retailers resulted in 1.2 to 1.9 percent higher simulated prices of several sets of WIC-provided foods. Although the majority of “re-shopped” A50 transactions went to large retailers with relatively low prices, such as supermarkets and supercenters, 7 to 8 percent of these transactions went to small stores with prices 29 to 47 percent higher than the statewide average.

“The Economics of Food Vendors Specialized to Serving the Women, Infants, and Children Program,” by Patrick W. McLaughlin, Tina L. Saitone, and Richard J. Sexton, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 101(1): pp. 20-38. doi: 10.1093/ajae/aay054, January 2019

Where Do WIC Participants Redeem Their Food Benefits? An Analysis of WIC Food Dollar Redemption Patterns by Store Type, by Laura Tiehen and Elizabeth Frazão, USDA, Economic Research Service, April 2016