What Can State-Level Reforms Tell Us About India’s National Food Security Act?

Highlights:

-

The Indian Government passed the National Food Security Act (NFSA) in 2013, which includes several reforms aimed at ensuring more efficient distribution of food through the Public Distribution System (PDS).

-

The NFSA is modeled after reforms implemented by the Indian State of Chhattisgarh beginning in 2004, which have helped improve the historically inefficient distribution of food grains in the state.

-

ERS analysis finds significant improvements in food security in Chhattisgarh during the past decade, but these improvements appear to be the result of reforms implemented prior to 2004 which are not included in the NFSA, creating uncertainty about the legislation’s effects on food security.

The National Food Security Act (NFSA) was passed by India’s Government in 2013 in response to persistently high levels of food insecurity and difficulty in efficiently distributing subsidized food grains to households through its food aid program. The act expanded the existing food aid program, known as the Public Distribution System (PDS). In addition to shifting food aid from a discretionary component of the social safety net to a legal right, the NFSA expands the number of households receiving subsidized food grains from the government; it also introduces a number of reforms aimed at improving the distribution of food grains in states where a large proportion of grains do not currently reach their intended beneficiaries.

Many of these changes are modeled after post-2004 PDS reforms implemented in the Indian State of Chhattisgarh, which helped to dramatically improve the distribution of subsidized food grains in the state. However, recent ERS research demonstrates that the improvement in the delivery of food aid in Chhattisgarh began prior to the PDS reforms that started in 2004. Increases in consumption of subsidized grains were likely the result of prior reforms and the political will to target the PDS. Thus, predicting whether the proposed reforms in the NFSA will help other states duplicate Chhattisgarh’s success is difficult.

ERS research on the effects of the PDS reforms in Chhattisgarh suggests that improvements in food security and nutrition could result if the NFSA is effective in improving the efficiency of food aid distribution. Following the reforms in Chhattisgarh, the share of the population consuming fewer than 2,100 daily calories in the state decreased and diet diversity improved. The experience of Chhattisgarh, where the PDS was performing poorly when the state was formed, provides evidence that improving the distribution of grains and reducing food insecurity in other states where the PDS still operates less efficiently is possible. However, PDS reforms did not shelter the state from the rising food prices or the financial crisis better than the rest of the country, and continued reforms are necessary in both national and state policies to target households experiencing sudden economic duress.

The Post-2004 Food Aid Reforms in Chhattisgarh Mirror Proposals in the National Food Security Act

PDS reforms in Chhattisgarh began shortly after the state’s formation in late 2000. In June 2001, the government began to grant licenses to private individuals to own and operate shops that deliver subsidized food grains, called Fair Price Shops (FPS). The number of FPSs in the state doubled between 2001 and 2004, which helped improve access for the rural poor to their rations of subsidized food grains. Chhattisgarh also restructured its procurement system by purchasing rice directly from local farmers in addition to receiving grains from the Central Government, which helps ensure adequate supply of food grains across the state.

Reforms continued even after a new government was elected, and they culminated in a number of well-publicized modifications that are very similar to a number of provisions in the NFSA. The 2004 Public Distribution (Control) Order discontinued the operation of FPSs by private dealers everywhere in the state and shifted operation primarily to local governments. Although private licenses expanded the number of FPSs across the state and helped households access subsidized food grains, the order was designed to try to further improve access to grains by decreasing reportedly pervasive corruption. The Order also contained a number of other provisions: delivery of grains to FPSs in the first week of the month, disclosure of allocations to FPSs to local governments and other local bodies, and inspections and social audits within specified intervals.

In 2007, Chhattisgarh expanded the number of individuals who were eligible to receive PDS rations by nearly 2 million people. Other smaller post-2004 reforms included a reduction in the price of subsidized food grains, computerization of records, text messages to report grain movements to citizens, electronic weighing machines for rations, publicly displayed lists of all ration card holders, and procedures for filing grievances. The reform process in Chhattisgarh led to additional food security legislation in the state in 2012, which further increased rations, provided rations of more nutritious foods in addition to food grains, and introduced more auditing mechanisms.

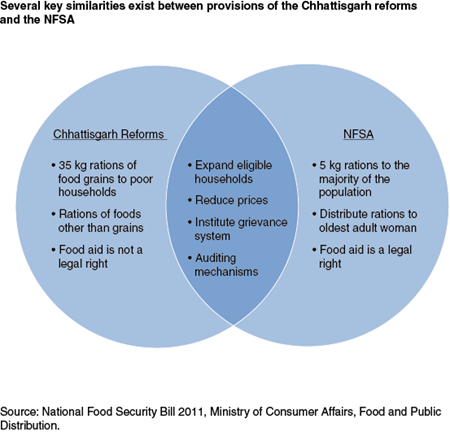

Delivery of Food Aid Began To Improve in Chhattisgarh Prior to the Post-2004 Reforms

Many of the post-2004 reforms have been credited with dramatically improving the distribution of food aid in Chhattisgarh. Furthermore, a number of these reforms have been adopted by the NFSA in hopes of improving the distribution of food grains in states where a majority of subsidized grains do not reach their intended beneficiaries. Similar to the Chhattisgarh reforms, the NFSA increases the share of the population entitled to food grain subsidies, establishes procedures for filing grievances, and introduces a number of auditing mechanisms designed to reduce the diversion of grains to the open market for a higher price.

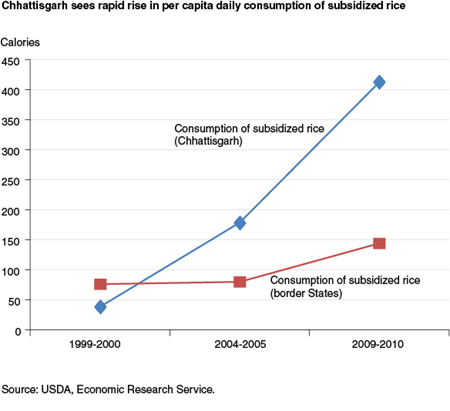

Given that many provisions of the NFSA were modeled after the post-2004 reforms in Chhattisgarh, a closer examination of the effects of the Chhattisgarh reforms could be useful to anticipate the potential effects of the NFSA. ERS researchers recently estimated the impact of the Chhattisgarh reforms on the availability of subsidized food grains. To do this, the researchers estimated PDS rice consumption for Chhattisgarh and regions bordering Chhattisgarh between 1999 and 2010 to analyze the causes of growth in PDS rice consumption.

ERS estimates illustrate two important points regarding the improvement in the PDS in Chhattisgarh. First, the increase in PDS rice consumption in Chhattisgarh, in both absolute and relative terms, began prior to the post-2004 PDS reforms. Those earlier reforms, which dramatically increased the number of FPSs, combined with the political will to target the food aid program, are likely responsible for this increase.

Although PDS rice consumption continued to increase between 2004 and 2009-10 in Chhattisgarh, consumption also increased in states bordering Chhattisgarh and across all of India. The consumption growth outside of Chhattisgarh is at least in part due to a food price spike and the global financial crisis. While the PDS makes a ration of grains available to households above the poverty line, the price is much higher than other PDS grains and is not widely used by households. However, the rising grains prices and negative income shocks likely made this ration more attractive to above-poverty-line households. When compared to country-wide growth in consumption of subsidized rice, the growth in consumption in Chhattisgarh following the post-2004 reforms is muted.

Research results suggest that the pre-2004 reforms of Chhattisgarh had a strong positive impact on PDS rice consumption, and these reforms and other social and political factors likely continued to play a role in the growth of PDS rice consumption after 2004. In their absence, it is possible that Chhattisgarh would not have witnessed such a large increase in PDS consumption. Taken together, these findings cast doubt on whether other states will be able to replicate Chhattisgarh’s success with the implementation of the NFSA.

Increases in the Availability of Subsidized Grains Led to Improvements in Food and Nutrition Security in Chhattisgarh

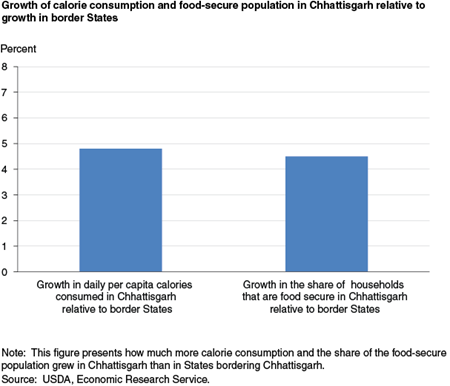

Whether the NFSA will improve distribution of food grains in states where delivery is most inefficient is uncertain. ERS analysis of the pre-2004 Chhattisgarh reforms suggests that greater availability of subsidized food grains can improve food security and nutrition. If implementation of the NFSA succeeds in its goal to ensure that more subsidized grain reaches households that need it the most, the result could be country-wide improvements in food security.

The first half of the 10-year period analyzed by ERS researchers—the years between 1999-2000 and 2004-2005—was a period in which no other states bordering Chhattisgarh implemented large-scale PDS reforms and in which food prices were relatively stable. This allowed ERS to better isolate the effects of increased availability of subsidized food grains by comparing the change in food security in Chhattisgarh with that of bordering states. The comparison is necessary to control for trends in calorie consumption across all of India and to estimate what would have happened in Chhattisgarh in the absence of reforms to the food aid program.

Over this period, ERS researchers found little change in both total calorie consumption and the food-insecure population in Chhattisgarh. However, there was a significant decline in calorie consumption and accompanying increase in the food-insecure population in bordering states and the rest of India, and increased food aid helped prevent similar drops in estimated calorie consumption in Chhattisgarh. In addition to the relative increase in calorie consumption in Chhattisgarh, increased food aid led to an increase in diet diversity (which is associated with better health outcomes) relative to border regions.

Importantly, these results are driven by households eligible for the largest subsidies, and researchers found no evidence that ineligible households made any changes in their diets. Additionally, these results do not appear to be driven by improvement in other aid programs in Chhattisgarh. These changes in food security and nutrition are not being driven by unrelated trends in consumption, as there are no differences in consumption growth between Chhattisgarh and border states in periods prior to the Chhattisgarh reforms.

Although expansion of the PDS between 1999-2000 and 2004-2005 in Chhattisgarh did help improve food security, the continued expansion of the PDS after that period (2004-5 and 2009-10) did not improve food security relative to border regions. This period was marked by the food price crisis and global financial crisis, which negatively affected households across all of India. Each of these factors could help dampen the improvement in food security in Chhattisgarh relative to neighboring states. Continued reforms are likely necessary in both national and state policies to target households experiencing sudden economic duress.

What Are the Implications for the National Food Security Act?

Based on the experience of Chhattisgarh, predicting how the NFSA might affect the distribution of subsidized food grains in states where the majority of subsidized grains do not reach their intended beneficiaries is difficult. The post-2004 reforms in Chhattisgarh, which are included in the NFSA, appear to have been effective at improving the availability of subsidized food grains, but the changes were operating in conjunction with the political will to make efficient delivery of food aid a priority and the pre-2004 reforms that helped dramatically increase the number of shops devoted to delivering subsidized food grains. Thus, it is possible that the NFSA will not improve the availability of subsidized food grains in states where households continue to lack easy access to shops distributing food aid.

Chhattisgarh’s experience suggests that food security and nutrition can improve in states where subsidized food grains are efficiently distributed under the NFSA. As states continue to improve the distribution of subsidized food grains, pushed in part by the NFSA and in part by national attention to the issue, millions of households can use the savings on food grains to help improve overall calorie consumption and diet diversity. Additionally, the NFSA can help provide an extra layer of income support through the savings on grains consumption that is not spent on food. Thus, the NFSA will likely be an important tool to combat persistent malnutrition and poverty.

Estimating the Range of Food-Insecure Households in India, by Sharad Tandon and Maurice Landes, USDA, Economic Research Service, May 2012

The Impacts of Reforms to the Public Distribution System in India's Chhattisgarh on Food Security, by Prasad Krishnamurthy, Vikram Pathania, and Sharad Tandon, USDA, Economic Research Service, March 2014

“The Sensitivity of Food Security in India to Alternate Estimation Strategies”, Economic and Political Weekly XLVI (22), 92-99, May 2011

“Public Distribution System Reforms and Consumption in Chhattisgarh: A Comparative Empirical Analysis', in Economic and Political Weekly, 49(8), pp. 74-81, February 2014