Creating Rural Wealth: A New Lens for Rural Development Efforts

Highlights:

-

Creating and maintaining a broad portfolio of wealth may be central to sustainable rural prosperity. However, the impacts that rural development strategies have on wealth and the impacts of existing wealth on those strategies are generally not well understood.

-

The success of rural wealth creation strategies is affected by several factors, including the temporal and spatial context, interrelationships among different types of wealth, the value of maintaining a portfolio of different types of wealth, and the benefits and risks of local ownership of assets used for rural development.

-

Further research to identify 'what works where' in strategies for creating and maintaining rural wealth, to measure the interactions and dynamics of different forms of wealth, and to assess the impacts of wealth portfolios and local ownership may contribute to a better understanding of how to attain sustainable and broadly shared rural prosperity.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, economic policy is understandably focused on jobs and income. As important as these indicators are, investment that strengthens the Nation's public and private capital base is key to long-term prosperity. Rural economic development efforts build on previous investments made in a broad range of assets, such as transportation and communication infrastructure, agricultural technologies, education and training, and preservation and development of natural resources.

Recognizing the connection between rural wealth and economic prosperity, rural development practitioners have begun to focus more attention on investing in a broad set of assets and building upon linkages among different types of assets. For example, the Appalachian Regional Commission has embraced an 'asset-based development' approach, emphasizing investment strategies that build upon the cultural, natural, physical, and leadership assets of Appalachian communities. The Ford Foundation has launched a program to promote wealth creation in poor rural communities that emphasizes a demand-driven approach linked to particular value chains and focuses on creating seven forms of wealth, including the value of physical and natural assets, but also less tangible assets.

Despite this increased focus on wealth creation, knowledge about wealth in rural areas--whether in a narrow or in a more comprehensive sense--and how it can be created and measured, is still limited. To begin addressing this information gap, ERS researchers recently completed an extensive review of research related to rural wealth creation, developed a framework for explaining the wealth creation process, and provided examples of indicators that could be used in the design, implementation, and evaluation of rural development strategies.

This article highlights lessons from the review concerning how a wealth creation perspective can inform and improve the efforts of rural communities and others seeking to promote sustainable rural prosperity. Five key lessons for rural economic development strategies emerged from the report. First, wealth creation is context dependent. Second, it is critical to understand the interrelationships among multiple forms of wealth. Third, degrading some types of assets may undermine the benefits of investing in others. Fourth, diversifying assets may reduce risk. Finally, local ownership has benefits but may also entail risk.

Wealth Creation Strategies Are Often Highly Context Dependent

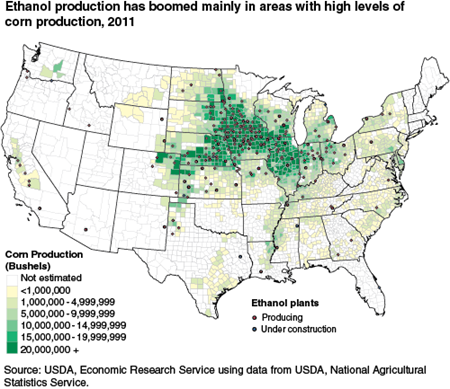

Both temporal and spatial factors can influence opportunities for rural wealth creation. For example, the ethanol production boom that began in the early to mid-2000s was stimulated by rising prices of oil and gasoline relative to the price of corn, improvements in the efficiency of ethanol processing technology, and Federal and State government policies that provided incentives for ethanol production, all of which contributed to increased profitability of ethanol production. These factors, together with comparative advantages of particular locations for ethanol processing due to favorable access to corn production, transportation infrastructure, and other requirements for ethanol refining and distribution, led to rapid expansion of ethanol plants in many rural communities, especially in the Corn Belt.

In rural places lacking these advantages, ethanol production is less likely to be profitable, and efforts to promote it could retard rather than promote wealth creation. Even where such advantages exist, changes in the temporal context, such as changes in the relative price of ethanol and corn (the major feedstock used to produce ethanol), have reduced profits and caused some plants to go out of business.

Other emerging energy industries in rural areas are also highly context dependent. For example, wind power development has mostly occurred in areas of the Great Plains, Mountain, and Midwest regions with strong wind potential and favorable access to the electric grid. This development was promoted by rising electricity rates, improved technology, and government policies. The boom in natural gas production in recent years resulted from improvements in drilling technologies, including horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing; the availability of large natural gas deposits in particular regions; favorable gas prices for much of the 2000s; and policies in some States allowing or encouraging drilling. As with ethanol production, these factors vary across rural areas and over time. For example, a recent decline in natural gas prices following a rapid increase in production slowed the pace of expansion.

Context is critical for many other rural development opportunities as well. For example, many rural communities close to metropolitan centers and with adequate transportation infrastructure develop as bedroom communities, with commuters providing a major share of the local population and income base. Rural towns located in central places with links to transportation networks may develop as regional hubs, emphasizing provision of retail and public goods and services. Some rural areas develop as part of a knowledge and innovation cluster, particularly in areas with favorable access to a university or other research center (e.g., Montana's biotechnology cluster). Such opportunities are not available for many rural areas in more remote locations, however.

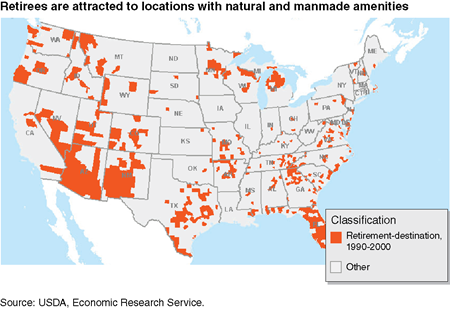

Among the most rapidly growing rural counties during the 1990s were those that had favorable natural amenities and entrepreneurial talent. Such places appear to be better able to attract and retain the 'creative class,' whose relatively high levels of education, income, and entrepreneurial capacity can contribute to more rapid rural economic growth. These advantages, of course, do not occur everywhere in rural America and can change over time due to broader changes in the economy, demographic shifts, or changes in the local context. For example, the ability of people to move to high natural amenity areas may have been limited by the recent fall in housing prices and the Great Recession. Over the next few decades, however, the number of people moving to such areas is likely to swell as the baby boom generation retires.

Rural places with less favorable natural resource endowments may need to consider other wealth creation strategies more suited to their context. Some areas have sought to attract tourists through the development of casinos. Since the late 1980s, a boom in casino development has occurred in many Native American communities and in locations along the Mississippi River and its major tributaries, facilitated by changes in Federal and State laws and the lucrative returns possible in locations with favorable access to major urban centers. In more isolated rural places, the scale of casino development and the local economic impacts have been much smaller.

Other endowments and investments may also attract people to rural areas. Some regions have cultural or historical endowments that have been the focus of tourism development efforts, such as investments along the Blues Highway in Mississippi or along the Crooked Road--the heritage music trail in southwestern Virginia. Retirees may be attracted to places that have manmade amenities and services such as golf courses, adult education opportunities, and health care facilities, even where natural amenities are limited. The attraction of a low crime rate, low housing costs, social cohesion, and a simpler lifestyle can bring migrants to even remote rural areas--especially people who grew up in such areas--if efforts are made to recruit and welcome them. With the expansion of broadband service into rural areas, opportunities are increasing to attract telecommuters and Internet-based businesses and services.

Interrelationships Among Multiple Forms of Wealth Are Often a Key to Success

Successful wealth creation efforts often rely on synergies among multiple forms of capital and investments. For example, the ability to attract the creative class--representing a form of human capital--to rural areas appears to depend on natural amenities in rural areas, as noted above. More generally, strategies to attract and retain businesses, residents, and visitors to rural areas depend on a range of public and private assets and investments affecting the quality of life and the ability to conduct business. These include roads, communications, water and sewer systems, schools, health care services, and recreational facilities.

Cluster-based development strategies, which seek to exploit the advantages of developing clusters of linked competitive activities in a region--the semi-conductor industry and the wine industry in California are prototypical examples--inherently build on multiple forms of capital. These include physical infrastructure, such as access to transportation and communications infrastructure; human capital, embodied in the people working and interacting in these activities; the knowledge or intellectual capital that is developed and shared among these people; social capital, reflected in formal and informal networks among firms and professionals that facilitate knowledge flows and innovation; and the financial capacity to finance new investments provided by banks and venture capital firms.

Synergies among different types of wealth may occur simultaneously or sequentially. In many cases, multiple types of investments are needed at the same time for an area-wide wealth creation effort to be effective, such as the need to recruit and train school staff (human capital investment) when a new school is constructed (physical capital investment). In other cases, the synergies may occur over time, as investments in one type of capital increase the feasibility or returns to subsequent investments in other types. For example, increases in local income and tax revenues resulting from an investment in a new manufacturing plant or casino may enable subsequent investments in schools, health care facilities, or other assets. As these other investments take place, the community may find it easier to attract and retain businesses and residents, leading to further improvements in physical, human, and other forms of capital.

Interactions among different forms of wealth may also involve substitutions rather than synergies. For example, there may be greater area-wide sustainable wealth effects if flooding risks in a river delta are managed by restoring and preserving wetlands rather than by building higher levees.

Regardless of whether interactions among different assets are simultaneous or sequential, or involve synergies or substitutions, investment efforts are less likely to be effective in promoting rural prosperity if such interactions are not taken into account. This, together with the context dependence of effective strategies, highlights the potential benefit of developing regional and local capacities to plan and implement investment strategies that consider multiple assets. One current effort to help develop such capacities is USDA's Stronger Economies Together (SET) program, which involves university extension experts assisting local entities in more than 40 multicounty regions to plan and implement investment programs.

Degradation of Some Types of Assets May Undermine Benefits of Investing in Others

Development strategies that invest in some assets while degrading others that are important for people's welfare may undermine the prosperity of a community or region. For example, resource extraction activities such as mining or logging can generate jobs and income in these and related sectors but may reduce the natural amenities of a location if the environmental consequences of these activities are not well managed. Such impacts could inhibit local economic development if they discourage people from living in or visiting these locations. Debate about the adverse environmental effects of mountaintop removal in coal mining or hydraulic fracturing in shale gas development reflects this concern, although evidence is limited on how economic development has been affected to date by these activities.

Conversely, a shift away from reliance on environmentally destructive activities may lead to greater growth and wealth creation, though this is also likely to be context dependent. For example, recent research finds that after the Northwest Forest Plan sharply reduced timber harvests in Oregon beginning in 1994, population, income, and property values grew faster in forest-adjacent communities than in communities more distant from the forest. An exception was logging and mill towns, which suffered losses initially but recovered to growth rates comparable to other communities after 2000.

Adverse social impacts of wealth creation strategies also may undermine their net benefits. For example, although casino development has contributed to increased income and employment and accumulations of financial and physical wealth in some rural communities, some evidence points to substantial social costs associated with the casino boom, including increased rates of pathological gambling, bankruptcies, crime, substance abuse, and other social problems. Whether such costs outweigh the economic benefits is a matter of ongoing debate.

Investing in a Diverse Portfolio of Assets May Reduce Risks

In addition to synergies among different types of investments, investing in a diverse portfolio of assets can help to reduce the economic risks facing rural communities. For example, a farming community whose primary economic activity is producing corn could be harmed by a sudden fall in corn prices. However, if members of that community invested in an ethanol plant, a fall in corn prices could boost their profits from ethanol production, helping to offset the corn price risk. Of course, if the fall in corn prices were due to a fall in demand for ethanol, owning an ethanol plant would not offset that risk. Other types of investments whose returns may be negatively correlated with ethanol demand--such as livestock production--or are not linked to the price of ethanol and corn--such as other manufacturing or services--could help to address such risks.

Local Ownership Can Increase the Local Benefits of Wealth Creation Strategies But There Are Risks

Rural development practitioners often argue that local ownership is essential for wealth creation strategies to broadly benefit people in rural areas. There are many reasons local ownership can be helpful. Local owners may be more likely to spend the profits they earn in their community, generating greater local economic impact. Local owners may have a greater stake and take greater interest in the local community than absentee owners, possibly hiring local people to a greater extent, investing more in other local businesses or charities, or being less likely to abandon the community for greener pastures elsewhere.

Although local ownership has advantages, it also involves potential tradeoffs and risks. Investors who focus too much of their investment portfolio on local assets may miss opportunities to make investments elsewhere that yield higher returns or have lower risks. Failure of a locally owned plant can have larger ripple effects on a local economy than that of an absentee-owned plant, because the losses faced by the owners ripple through the local economy, just as the positive ripple effects of a profitable locally owned plant are greater.

Impacts of Rural Development Strategies on Wealth Are Generally Not Well Understood

Just as a business or household would not have a clear understanding of its economic well-being if it considered only its income and expenses and ignored its assets and liabilities, rural communities and regions need information about their asset base when designing and implementing rural development strategies. Unfortunately, data and research measuring rural wealth are quite limited.

Viewing rural development efforts through a wealth creation lens yields insights that can help inform and improve those efforts. Understanding the context and the interrelationships among different contexts and multiple forms of wealth is important, as is considering the possibility that degrading some types of assets may undermine the benefits of investing in others. Diversifying assets may help to reduce risk, while the benefits of local ownership should be weighed against a potential increase in risk. Further research to identify 'what works where' in strategies for creating and maintaining rural wealth, measure the interactions and dynamics of different forms of wealth, and assess the impacts of wealth portfolios and local ownership may contribute to a better understanding of how to attain sustainable and broadly shared rural prosperity.

Rural Wealth Creation: Concepts, Strategies, and Measures, by John Pender, Alexander Marré, and Richard Reeder, USDA, Economic Research Service, March 2012

Federal Forest Policy and Community Prosperity of the Pacific Northwest, Choices Magazine, April 2012

Sustainability and the Measurement of Wealth, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, December 2010, Sustainability and the Measurement of Wealth

The Changing Wealth of Nations: Measuring Sustainable Development in the New Millennium, World Bank, February 2011