Incidence of Absent Landlords Has Little Effect on U.S. Agriculture Real Estate Values, Research Shows

Highlights:

-

83 percent of nonoperator landlords in 2014 lived within 200 miles of the parcels they rented out.

-

The prevalence of absent landlords (nonoperator landlords who live far from the leased farmland) was consistently higher in States with lower land values.

-

The 2012-17 rate of gain in land values was relatively constant regardless of the prevalence of absent landlords.

The role of absent landlords—who live long distances from the land they rent out to farm operators—has captured the interest of policymakers and academics seeking to understand their role in farmland management and other aspects of local economies and resource management. In response to a congressional request, USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS) researchers studied how longer distance-landlords affect the economic health of U.S. agricultural production. Looking into the association between landlord absenteeism and agricultural real estate markets, researchers found a greater prevalence of absent landlords in counties and States with lower rents and land values. At the same time, they found no association between absent landlords and recent changes in rents or land values.

Nonoperator landlords own the majority of rented farmland in the United States, and most live close enough to their land to visit regularly. Those who live farther away are known as absent landlords, and because of the distance from their land, they may face different incentives than local landlords or farmers who operate their own property.

For this study, ERS researchers examined a variety of measures of long-term economic and agricultural health for 25 States, using data from the USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service, Census of Agriculture and the 2014 Tenure, Ownership, and Transition of Agricultural Land (TOTAL) survey. The TOTAL survey is national, but it is not representative of the agricultural sector down to the county level, and at the State level, it is only representative of the 25 most important agricultural States by cash receipts. However, TOTAL contains the most complete information on the characteristics of nonoperator landlords and their tenants.

Challenges in Defining ‘Absent Landlords’

A fundamental challenge of studying absent landlords is defining a population of interest. Economists and other agricultural stakeholders do not have a specific definition for “absent landlord,” although some local studies refer to “out-of-state” landlords as absent landlords. The TOTAL data allowed ERS researchers to quantify the distance between land location and landlord mailing address, which is particularly effective when landlords live just across a State line from their land.

While some nonoperator landlords live in major U.S. coastal cities, most live in major cities in agricultural States and are more likely to be retired farm operators or descendants who inherited agricultural land, rather than investors from more distant parts of the country.

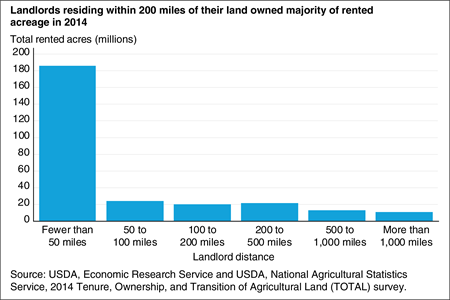

Landlords residing within 50 miles of their land owned the majority (67 percent) of agricultural acreage in 2014, and landlords residing within 200 miles owned 83 percent of the acreage. Nonoperator landlords who lived farther away from their rented land tended to have larger holdings than those who lived nearby.

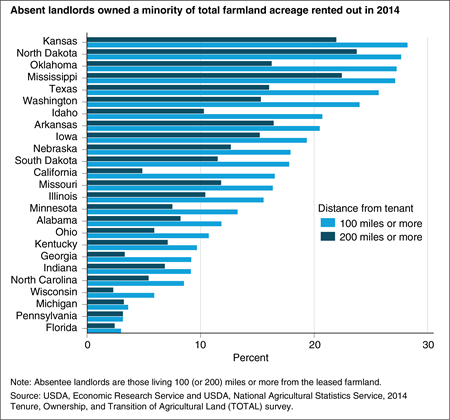

ERS considered two groups of absent landlords: those whose mailing address was more than 100 miles from their rented land and those residing more than 200 miles from their rented land. Figure 2 shows the percentage of acreage owned by absent landlords for the 25 largest agricultural States, using both the 100-mile and the 200-mile threshold definitions.

In the States included in the chart above, less than 30 percent of rented acreage in 2014 was owned by absent landlords using either distance-based definition. Using the second definition with a 200-mile threshold, researchers found that absent landlords exceeded 20 percent of total rented acreage in only three States—Kansas, North Dakota, and Mississippi. While absent landlords owned a sizable percentage of farmland acreage in some States, they did not own a majority of U.S. farmland in any State.

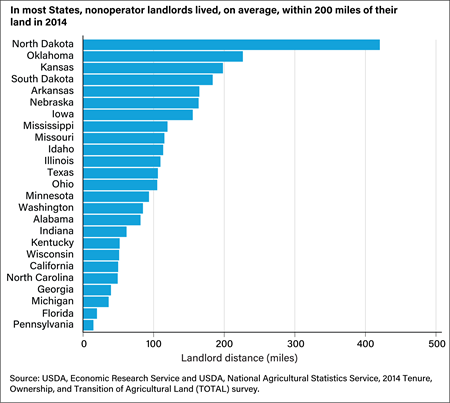

ERS examined one final measure of landlord absenteeism: the average distance between nonoperator landlords and their rented land, shown in the chart below. This average distance was less than 200 miles for the majority of States included in the analysis. North Dakota was an outlier, with an average distance of more than 400 miles, even though fewer than 30 percent of landlords live more than 200 miles away.

Absent Landlords May Affect Land Values

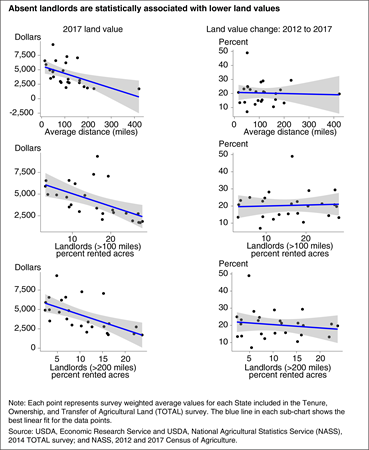

As participants in farm real estate markets, absent landlords can potentially influence land prices. To assess absent landlords’ influence on farmland values, ERS researchers compared the land values in each State included in the TOTAL survey to the State’s corresponding measure of nonoperator landlord absence. This analysis included:

- Share of total rented acreage owned by nonoperator landlords with mailing addresses more than 100 miles from their rented land.

- Share owned by nonoperator landlords more than 200 miles from their rented land.

- Average distance between the landlord’s mailing address and their rented parcels.

The percentage changes in land values reported in the 2012 and 2017 Census of Agriculture for each State is also shown.

Researchers found a negative trend between the three measures of landlord absenteeism—the percentage of those who live within 100 miles, the percentage within 200 miles, and average distance—and the price of agricultural land in 2017. For each measure of landlord absenteeism, the line of best fit trended downward, indicating that higher rates of absenteeism are associated with lower average land values. This evidence, in isolation, does not allow the researcher to distinguish whether absent landlords hold higher shares of farmland in States with lower land values because it is more affordable to purchase, or because land values are lower in those States because of the effect of higher shares of absent landlords.

The number of absent landlords had little to no effect on how land values evolved over time. If absent landlords were directly influencing land values, the change in land values would be influenced by the level of landlord absenteeism. This finding suggests that the prevalence of absent landlords may not negatively influence the ability of farm operators to buy farmland by pricing them out of the market. Nevertheless, this analysis is exploratory in nature and, thus, cannot definitively identify causal relationships.

Absent Landlords in Agriculture – A Statistical Analysis, by Siraj G. Bawa and Scott Callahan, ERS, March 2021

Changing Farmland Values Affect Renters and Landowners Differently, by Nigel Key and Christopher Burns, USDA, Economic Research Service, February 2018

A Primer on Land Use in the United States, by Daniel Bigelow, USDA, Economic Research Service, December 2017

U.S. Farmland Ownership, Tenure, and Transfer, by Daniel Bigelow, Allison Borchers, and Todd Hubbs, ERS, August 2016

Major Land Uses, by Scott Callahan, USDA, Economic Research Service, March 2023