U.S.-Mexico Agricultural Trade: Opportunities for Making Free Trade Under NAFTA More Agile

Highlights:

-

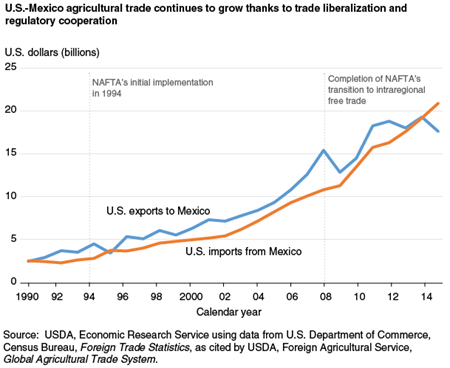

In 2015, the United States realized $17.7 billion in agricultural exports to Mexico and $21.0 billion in corresponding imports from Mexico, compared with $3.6 billion in exports and $2.7 billion in imports in 1993.

-

With the trade-liberalizing provisions of the North American Free Trade Agreement fully implemented, further growth in U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade will depend on means other than tariff and quota elimination.

-

A new joint study by USDA and Mexico’s agricultural secretariat identifies six areas of opportunity for facilitating U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade.

As part of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Mexico and the United States gradually eliminated all tariffs and quotas governing bilateral agricultural trade during a 14-year transition period from January 1, 1994, to January 1, 2008. The same period saw growing cooperation between the two countries on sanitary, phytosanitary, and other regulatory issues affecting the agricultural and processed food sectors—a process that continues to this day. Together, this sweeping trade liberalization and ongoing regulatory cooperation made possible a dramatic increase in U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade.

Now Mexico and the United States must look elsewhere for trade gains. Improving border infrastructure is one option, but expensive. For example, renovation of the Mariposa Land Port of Entry in Nogales, Arizona, cost about $250 million, while the Otay Mesa East Port of Entry—under construction between Tijuana, Baja California, and San Diego, California—is slated at $700 million.

Another way to foster growth in U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade is to modify border procedures in ways that make that trade more agile, allowing products to cross the border more quickly, easily, and efficiently, but without compromising governmental standards with respect to food safety, sanitary and phytosanitary conditions, and other regulatory matters. Improvements to border procedures can lower transaction costs, shorten transit times, and increase compliance with the rules governing bilateral agricultural trade. To explore opportunities for making U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade more agile, researchers from ERS; Mexico’s National Service of Agri-Alimentary Health, Safety, and Quality (SENASICA) in the Secretariat of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fishing, and Food (SAGARPA); and SAGARPA’s General Coordination of International Affairs conducted interviews with people from the private sector, government, and academia in Mexico and the United States who are knowledgeable about bilateral agricultural trade. Those interviewed included exporters, importers, customs brokerages, and industry associations that have direct experience with border procedures.

Interview respondents identified six general areas of opportunity for potentially making bilateral trade more agile. Exploiting these opportunities will require familiarity with current agri-food trends, the application of advanced technologies (particularly in information management), and continued cooperation by actors on both sides of the border.

Attention to the Agriculture-Related Aspects of Border Crossings and Inspections

The border crossing and inspection process is a critical control point, where requirements concerning food safety, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and other standards are enforced, in the shipment of agricultural goods from origin to destination. Problems at this juncture can impede the flow of agricultural trade, leading to higher transaction costs, slower transit times, and even outright losses of product due to spoilage or slippage. At the same time, the certification and inspection of agricultural imports serve to validate that these products may be safely consumed and do not present an unacceptable risk to the importing country’s plant and animal resources.

Interview respondents pointed to consistency in the implementation of standard inspection procedures as a vital issue and offered several examples of past inconsistencies, now resolved, concerning Asian vegetables destined for the United States and cattle hides destined for Mexico. Consistency in border inspections helps to ensure that border processes occur as planned for each shipment. Respondents emphasized that both government and the private sector have roles in making this process work. Government must be able to conduct inspections consistently, both over time and at different ports of entry, to discourage port-shopping by shippers and to ensure meaningful inspections. Personnel must have the specialized knowledge and skills—such as identification of insects, collection and testing of samples, and familiarity with all product standards—for carrying out inspections. Problems with the consistency of inspections for specific commodities can be addressed by additional supervision or training for inspectors.

The private sector, in turn, requires complete and accurate documentation about the products it trades between countries. Such documentation underpins the inspection process, the functioning of risk-based screening tools, and investigations of outbreaks of food-borne illnesses. In addition, exporters must ensure that their products remain in optimal condition from origin to destination. While these tasks fall to individual firms, one firm’s problems can hamstring other firms. For instance, a truck carrying a rejected shipment adds to traffic congestion and diverts inspectors who could be expediting another shipment that conforms to regulatory requirements. By this reasoning, activities such as refresher courses for exporters on how to comply with U.S. and Mexican regulatory requirements could benefit all trade participants.

Further Development of Risk-Based Inspection Systems

A risk-based inspection system allows governments to concentrate scarce budgetary resources on those agricultural products that present higher risks to consumers and agri-food producers. Making different systems compatible would allow the private sector to focus on satisfying a common set of inspection requirements (see box “Risk-Based Inspection Systems Target Scarce Resources”), while making sure that inspection protocols are compatible and reporting requirements transparent would help to ensure that the risks associated with a particular shipment are properly scored, to the potential benefit of both traders and regulators. Greater outreach might also generate suggestions from the private sector on how to improve existing risk-based inspection systems.

Pre-Clearance and Pre-Inspection Systems and Joint Inspection Facilities

Pre-clearance and pre-inspection systems provide a means for either locating parts of the inspection process away from the border or concentrating several steps of that process at a common facility operated jointly by both governments. The terms “pre-clearance” and “pre-inspection” are sometimes used interchangeably but have distinct meanings to certain government agencies, and the term “pre-clearance” can have different meanings across government agencies. For U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), pre-inspection refers to an official U.S. inspection of a shipment in a foreign country prior to the shipment’s arrival at the U.S. port of entry, while pre-clearance refers to a traveler who is permitted to enter the United States after the traveler and his or her baggage undergo immigration, customs, and agriculture inspection on foreign soil, thereby avoiding further processing or security screening upon arrival. Thus, for CBP, pre-inspection of a shipment does not mean that the shipment is cleared to enter the United States; that clearance is obtained later in the border-crossing process. For USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), pre-clearance refers to inspections of agricultural commodities conducted in foreign countries under the direct supervision of qualified APHIS personnel and in accordance with phytosanitary measures specified by APHIS.

Some segments of the U.S.-Mexico inspection regime already occur away from the border. For example, Mexico pre-clears fruit and vegetable imports from the United States at private-sector concessions located on the U.S. side of the border, and APHIS pre-inspects irradiated mangoes imported from Mexico. A new U.S.-Mexican facility in Tijuana, Mexico—adjacent to the U.S. Port of Entry in Otay Mesa—for pre-inspecting certain fruit and vegetable imports from Mexico under the NARP will be assessed at the end of a 180-day pilot period that started in January 2016. Similar joint facilities are a possibility for other ports of entry. Pre-inspection could also be extended to trucks and semi-tractor trailers used in short-haul, cross-border transit, as some in Mexico have proposed.

Advance Preparations for New Transportation Facilities and Shipping Routes

Advance preparations could be explored to ensure the consistent delivery of inspection services as bilateral trade evolves. Disproportionate growth of bilateral agricultural trade across ports of entry inevitably affects the demand for inspection services—a trade pattern that can be anticipated by the U.S. and Mexican Governments as they adapt their border operations to new trade patterns.

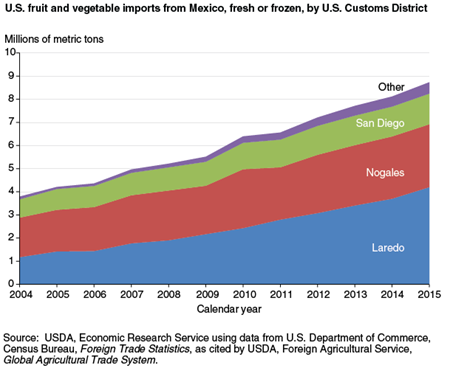

Imports of fruit and vegetables from Mexico have grown substantially in each of the three main Customs Districts for these imports—Laredo, Nogales, and San Diego—but much faster in the Laredo district, which encompasses both Laredo and Weslaco, Texas, among other ports of entry along the Rio Grande from Brownsville to Del Rio. In 2015, the Laredo Customs District was the entry point for 48 percent of U.S. fruit and vegetable imports from Mexico, versus 31 percent in 2004. This geographic shift was prompted in part by the inauguration, in 2013, of Federal Highway 40D between Mazatlán and Durango, Mexico, which reduced transit time through the Sierra Madres by about 4-6 hours. Also, fruit and vegetable production in central and eastern Mexico has expanded faster than in western Mexico. Between 2001-03 and 2012-14, Mexican production of fruit, vegetables, and dry legumes increased by 22 percent. Of the 10 Mexican States with the largest percentage increases in production over this period, all but 1 (Sonora) are closer to Laredo than to Nogales.

Complementary Activities for Single Window Environments

Both the Mexican and U.S. Governments have established single window environments for the submission of information needed to meet regulatory requirements related to international trade. The World Customs Organization defines a single window environment as “a system that allows parties involved in trade and transport to lodge standardized information, mainly electronic, with a single entry point to fulfill all import, export and transit related regulatory requirements.”

Use of Mexico’s Digital Window for Foreign Trade (VDMCE), or Ventanilla Única, became mandatory in July 2012. Ventanilla Única provides a single system for all of Mexico’s Federal agencies that oversee international trade. (USDA’s regulatory agencies currently have separate systems.) A planned second stage for Ventanilla Única would add electronic phytosanitary and zoosanitary certificates (E-certs) and risk-based inspection modules. The success of these enhancements will depend on the implementation of similar initiatives in the United States.

In the United States, the Automated Commercial Environment (ACE) is scheduled to become fully operational by the end of 2016. Mandatory use of ACE for the filing of all electronic manifests began on May 1, 2015, and mandatory use for all remaining electronic portions of the CBP cargo process is scheduled to begin on October 1, 2016.

With some coordination, the two Single Window systems could be used as platforms for streamlining the administrative requirements for bilateral agricultural trade. This effort could include instituting E-certs for the full range of agricultural products, consolidating or eliminating some types of documents, and lengthening the period of validity for certain documents. Each Government could organize outreach activities to train the private sector in navigating the Single Window systems. U.S. Customs and Border Protection is already doing this with respect to ACE in the form of webinars and training videos.

Creation of Formal Avenues for Regulatory Innovation and Convergence

Improved communication channels would facilitate greater input, particularly from the private sector, into the regulatory processes governing U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade. Interview participants offered many ideas for making bilateral agricultural trade more agile. Some ideas focused on specific commodities, such as a shorter monitoring period for scrapie—a fatal degenerative disease affecting the central nervous system of sheep and goats—in the voluntary U.S. export certification program for live sheep and goats.

Other suggestions were far more sweeping. For instance, the time required to test food imports and to identify insects found in agricultural shipments could be shortened by locating laboratories closer to the border. Already, the FDA deploys mobile labs at ports such as Nogales during peak import seasons, and SENASICA uses mobile labs to test for pathogenic microorganisms and toxic residues. Another possible approach—one that the Mexican Government has adopted for some of its testing needs—is the use of government-certified laboratories operated near the border by private firms or academic institutions.

Closer alignment of the schedules of border facilities with private-sector operating hours is another sweeping change that would be welcomed by people in the industry, some of whom envision a border that is open to agricultural trade 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. A round-the-clock border is not without its tradeoffs, however, in terms of costs, staffing, and the quality of inspections.

Risk-Based Inspection Systems Target Scarce Resources

The U.S. and Mexican Governments continue to develop, operate, and refine several risk-based inspection systems that allocate scarce budgetary resources based on the likelihood and severity of risks associated with different products.

The National Agriculture Release Program (NARP)—created by USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and jointly operated by APHIS and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)—provides a methodology for evaluating high-volume agricultural imports that are low-risk for the introduction of plant pests and plant diseases into the United States. Under the program, imports of NARP-approved commodities may be inspected less frequently under certain conditions. Currently, NARP applies only to commercial shipments of specific fruit and vegetables (fresh, frozen, processed, or semi-processed) from Mexico and several other countries.

Mexico’s Trusted User (UCON) program, operated by SENASICA, allows approved meat importers to operate with less frequent inspections of their purchases. The imported product must be inspected in the destination plant by an Official Veterinary Doctor or Authorized Third-Party Specialist, and the destination plant must be a Federal Inspection Type (TIF) establishment—a class of slaughtering/processing plants certified by the Mexican Government to have the highest sanitary standards and most advanced technological processing levels in the country.

The Predictive Risk-based Evaluation for Dynamic Import Compliance Targeting (PREDICT) system is used by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to help target high-risk shipments for examination and low-risk cargo for automated clearance. PREDICT provides a customized risk score for each import product (or “entry line”), based on numerical weights assigned to inherent risks, data anomalies, and data quality and the compliance histories of individual firms and products.

SENASICA is developing a new informatics system, broadly similar to PREDICT, called the Integral System of the Inspection Service (SISI). SISI uses scientific, statistical, legal, and technical information to determine the rate of inspection for a specific commodity, given different risk variables. SISI will be applied to all products (vegetable, animal, aquacultural, and fishing) regulated by SENASICA, including both domestically produced and imported product, at the firm and commodity level. SISI will allow for the expedited entry of some goods into Mexico, including merchandise that is considered to be of sufficiently low risk that it can be inspected at its destination.

Opportunities for Making U.S.-Mexico Agricultural Trade More Agile, by Steven Zahniser, Adriana Herrera Moreno, Arturo Calderón Ruanova, Sahar Angadjivand, Francisco Javier Calderón Elizalde, Linda Calvin, César López Amador, Nicolás Fernando López López, and Jorge Alberto Valdes Ramos, ERS, August 2016